Defying Boundaries: Azerbaijan’s Drag Star

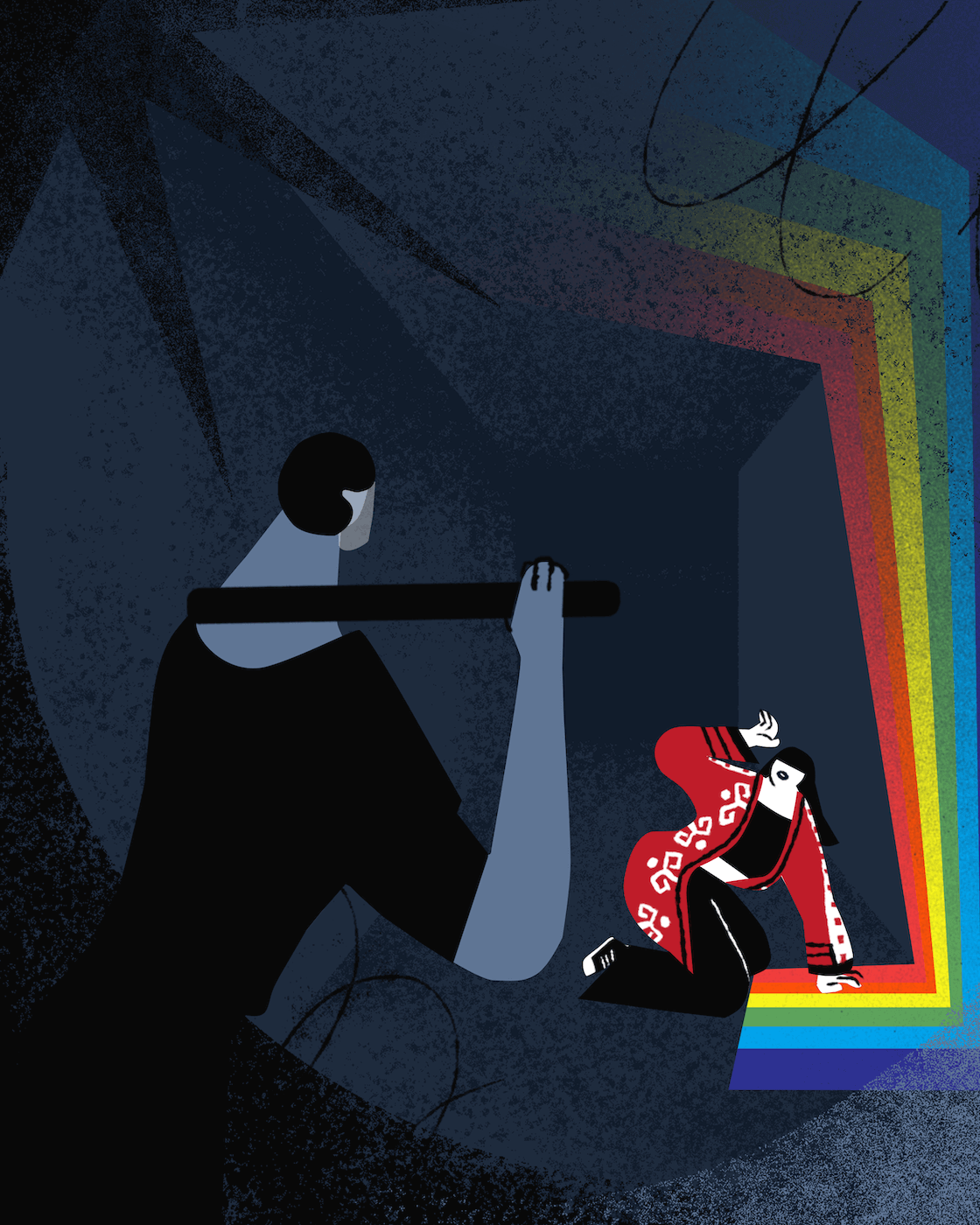

Hidden amidst the conservative landscape of Azerbaijan’s cultural scene, a few drag queens defy societal norms and push the boundaries of expression.

LGBTIQ+ activist Ali Malikov says there are several queer dancers, performers, and DJs in Azerbaijan, but they either have to hide their identities to be able to perform safely, or they are viewed as “marginal entertainers.”

Ali believes that the unsafe environment has curtailed the development of queer culture in the country. “You may have noticed that news coverage of queer people is about either death or arrests or any other survival-related issue. We are trying to survive and in these circumstances, it is hard to organise ourselves into wider activism or queer culture development,” they say. “Even when we attend usual clubs open to the public, the police raids them, attacks us and pushes us out of these clubs. We are not wanted here.”

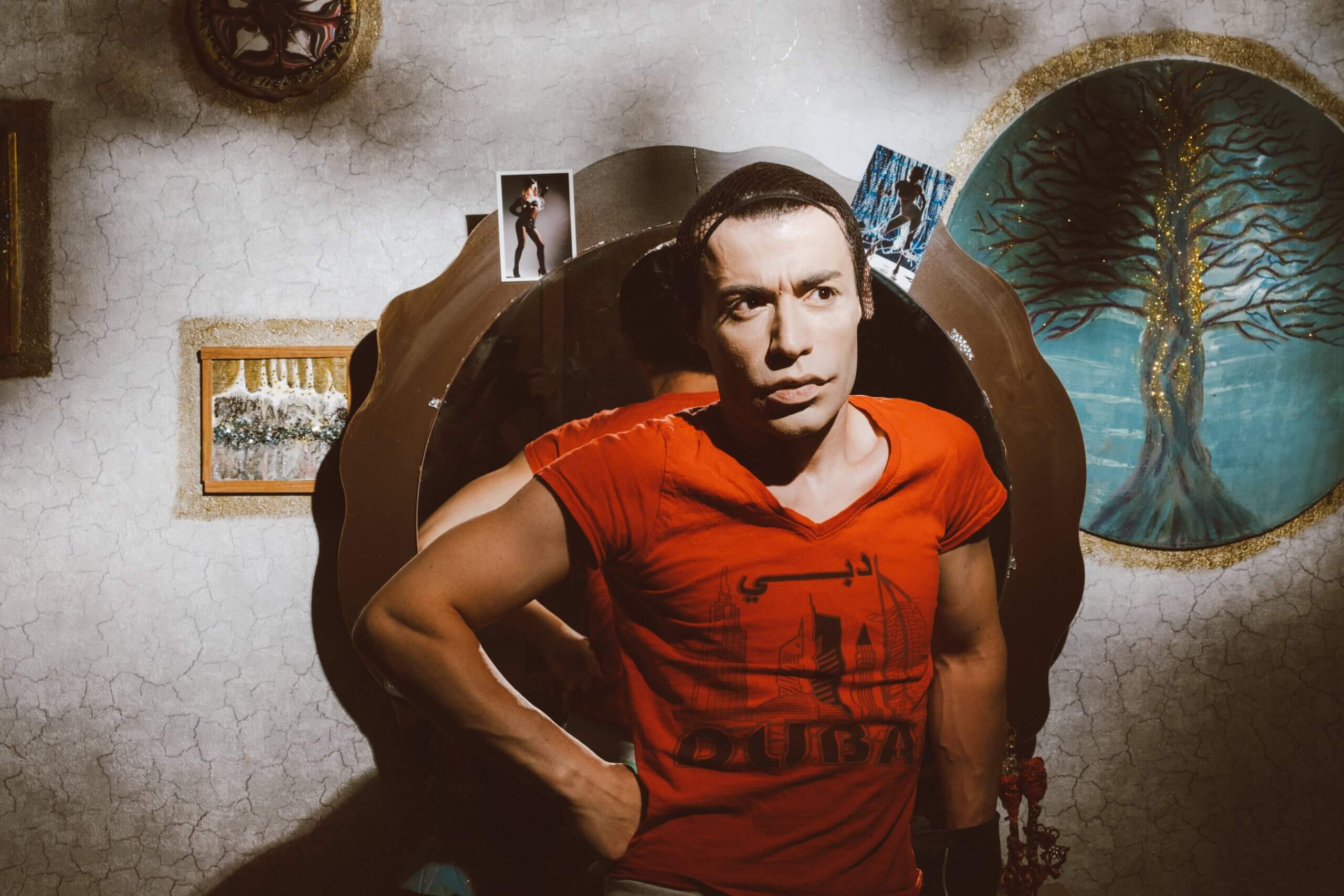

However, a few brave performers have forged a unique path, captivating select audiences in private gatherings and occasionally venturing beyond their homeland’s borders. One star among them is Seymur, the first drag artist in the country known by a stage name, Lady Slim. Her journey into the world of drag artistry showcases the resilience and determination of those who dare to challenge the status quo.

Born in 1987 in Azerbaijan, Lady Slim’s introduction to drag began unexpectedly, in Russia. After graduating from Baku State University with a degree in history, her passion for dance led her to explore the world beyond her homeland. It was in Moscow that she encountered drag culture for the first time, an encounter — she describes it as “fate” — that changed the trajectory of her life.

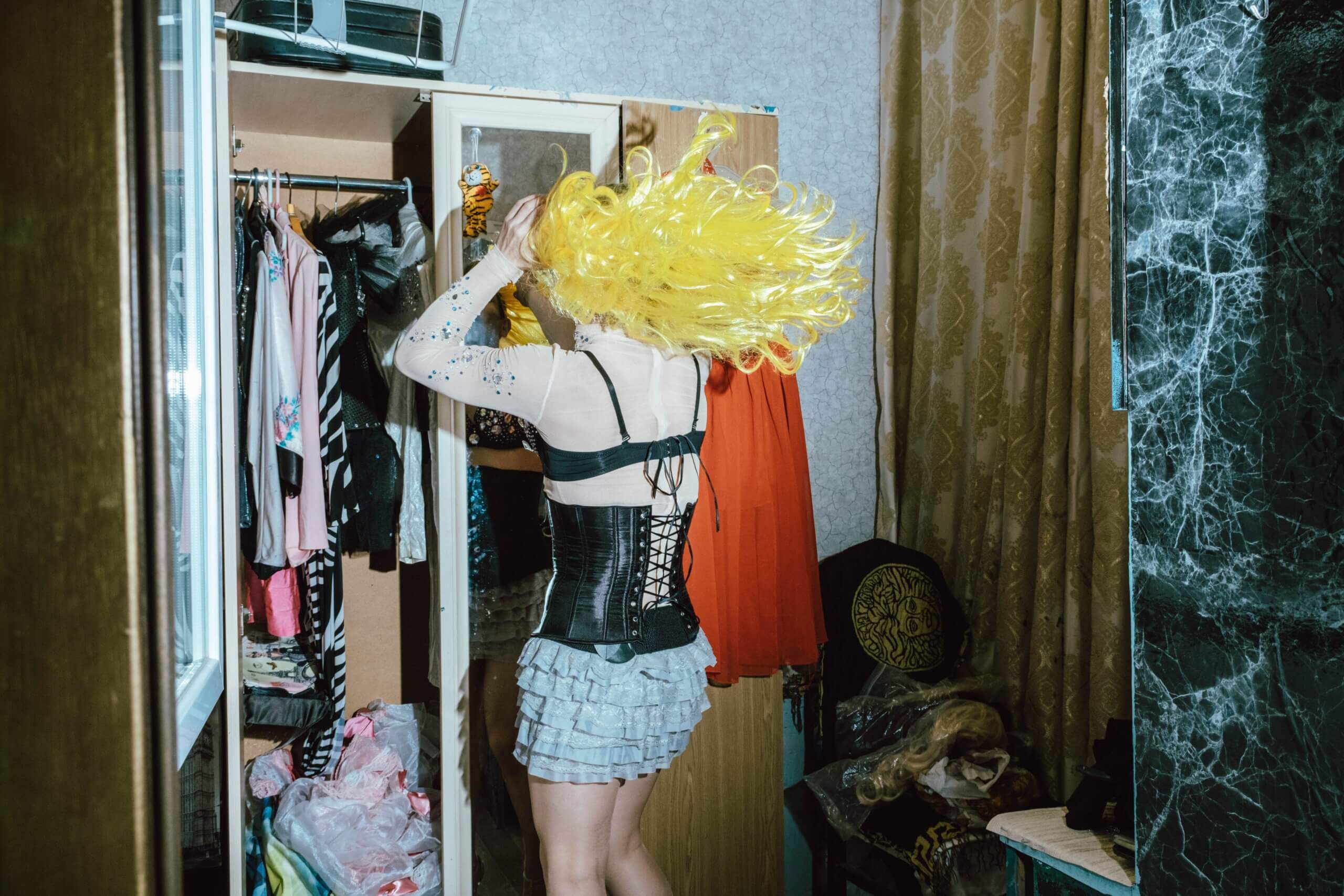

Drag queens, such as Lady Slim, are performers who dress in feminine clothes to dismantle societal norms surrounding gender. With heavy makeup, “falsies” to enhance their appearance, and daring outfits, these queens boldly challenge the patriarchal notions of femininity. Lady Slim’s natural dancing talent, combined with her dedication to perfecting her craft by studying performances of famous show-business stars like Lady Gaga, Ani Lorak, and Madonna, have earned her a devoted following.

Lady Slim’s performances have reached a broader audience through appearances on national TV channels in Azerbaijan. In 2010, for the first time, she performed on Azerbaijani Space TV in an entertainment competition called “Who Can Do What.”

She notes, however, that as attitudes towards queer individuals worsened in the country starting in 2015, doors began to close for artists like her. Invitations to perform dwindled, and recordings of her performances were erased from public platforms. Today, her work can only be found on her own social media channels.

“I love decorating my costumes with rhinestones, sewing new costumes from scratch, and coming up with new original looks.”

In Azerbaijani theatre, in the 19th century, female characters on stage were portrayed by male actors. The scarcity of actresses at that time prompted this cross-dressing phenomenon, but as the number of female performers grew, the practice gradually diminished. Today, there are times when male performers don women’s attire for comedic and light-hearted scenes, but it is essential to distinguish these characters from the revered drag queen art form.

Azerbaijan’s stance on queer rights remains problematic, with phobic sentiments prevailing within the government and society at large. Although same-sex sexual activity was decriminalised in 2000, discrimination, harassment, attacks, and arrests have become common for LGBTIQ+ citizens.

“The government, the media, the society consistently “others” us, and the result, unfortunately, is mass queerphobia,” notes LGBTIQ+ activist Ali Malikov.

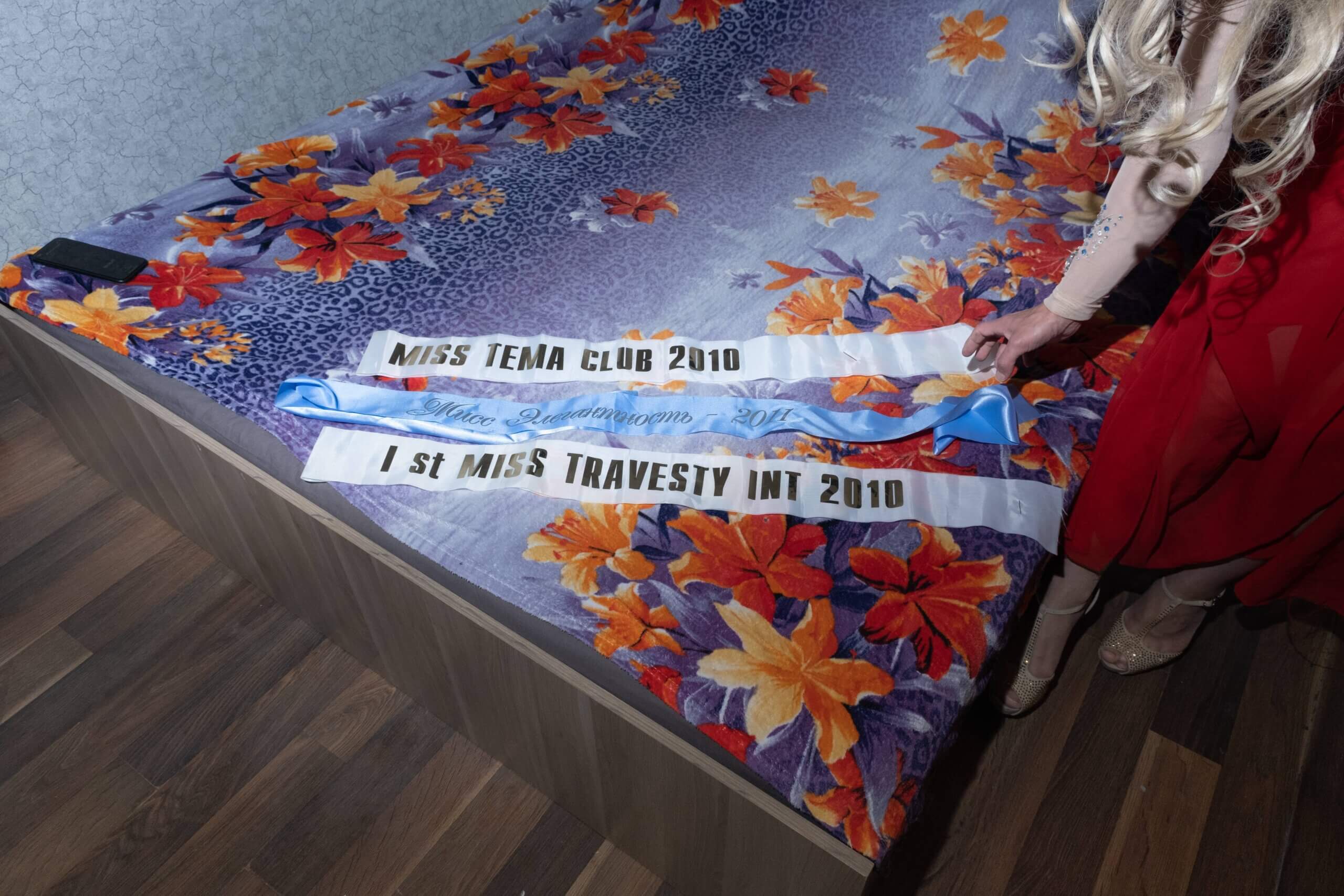

Despite these adversities, Lady Slim has remained resolute in her passion for performing, pushing forward, and making a name for herself both in Azerbaijan and internationally. She continues to captivate audiences worldwide, gracing stages in Turkey, Switzerland, Hungary, and even taking home awards from drag competitions in Ukraine and Moldova. Her success in the face of adversity serves as a signal of hope for those navigating the same challenges.

Within her own family, Lady Slim found acceptance and understanding. At first, her parents struggled to understand her career choice, but over time, they grew to appreciate it as a form of parody and embraced her journey. Lady Slim’s story stands in stark contrast to others in the community who have experienced rejection from their families, leaving her grateful for the love and support she receives from her parents.

There was a time when Lady Slim performed shows on national TV channels in Azerbaijan but eventually, they stopped inviting her and recordings of the performances were erased from the channels’ websites and social media pages. Today, videos of Lady Slim’s previous performances are only available on her own social media channels.

In Azerbaijan, Lady Slim’s performances predominantly cater to all-female private parties. Though she occasionally receives invitations to perform at children’s birthday parties, she believes that it is the women attending the events who seek her captivating show. She cherishes the open-mindedness and curiosity of young children, who watch with fascination, free from the societal biases that often plague adults.

“I always try to go to the event location about half an hour before because all the dressing and makeup take a lot of time.”

Lady Slim loves to decorate her home herself. She made all the decorations in her apartment.

As Azerbaijan grapples with its stance on LGBTIQ+ rights, artists like Lady Slim remain at the forefront of a cultural movement that challenges norms, fosters acceptance, and paves the way for a more inclusive society. Despite the adversity and bigotry she encounters, her talent and determination shine through, reminding the world that drag culture is more than just entertainment; it is an embodiment of courage, freedom, and the power to redefine social norms.

Lady Slim’s awards from drag show competitions in Odessa, Ukraine in 2010.

Afsana Tahirova contributed to the text and Elturan Mammadov assisted in the photoshoot.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“This Is My Feminist Manifesto”

Behind the Mask: Contemporary Drag Culture in Kazakhstan

Chemo Dao

Queer Self-Expression in Kyrgyzstan: Between Cultural Norms and Personal Values

Three Stories from Moldova: Drag, Cinema, Literature

Drag in Armenia: An Evolution of the Artform

Guess the Fact – Queer Artist Edition

“Discover Your Own Point of Tension and Pleasure. Trust Both”

Colourful Petals

Emotions. Feelings. Uzbekistan

Peculiarities of Running LGBTQ Spaces in Kazakhstan

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

A Story of One Migration

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

No Trauma, No Drama. Rewriting Media LGBTQI+ Narratives

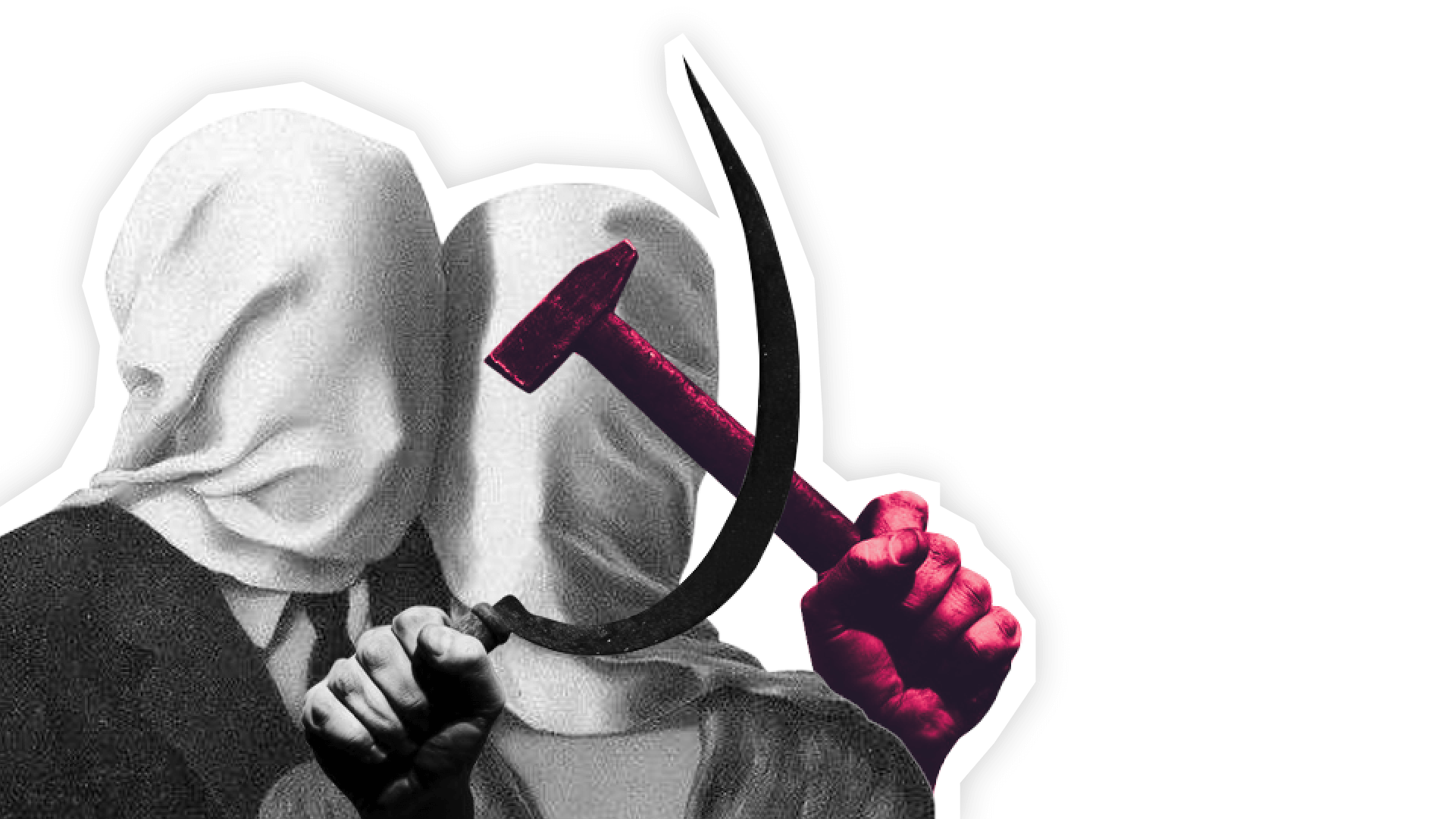

What if homophobia in Central Asia is a product of colonialism?

Russian Propaganda’s Influence on Soviet and Post-Soviet Homophobic Narratives in South Caucasus

Russian Colonialism and Homophobia in Moldova

Migration Is the Path to Freedom. A Photo Report about Sumaya

Russia’s Homophobic Law Inspires Azerbaijani Political Elites

“I Put a Lid On My Sexual Orientation, I Buried It”: Life of LGBTQ+ People in the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine

Non-traditional Values: Did Uzbekistan Inherit Homophobia and Family Concepts from Soviet Union?

Gay Pride Parade, “Dazhynki” or White March: which holiday suits “Belarusians of the future”?

Beyond Blurred Existence