“Discover Your Own Point of Tension and Pleasure. Trust Both”

Katherina Turenko is a journalist, editor, photographer and activist. She identifies as queer and is passionate about erotic photography. In this candid and personal text, Katherina shares how she uses photography to understand herself and others on a deeper level.

How photography became a passion and routine

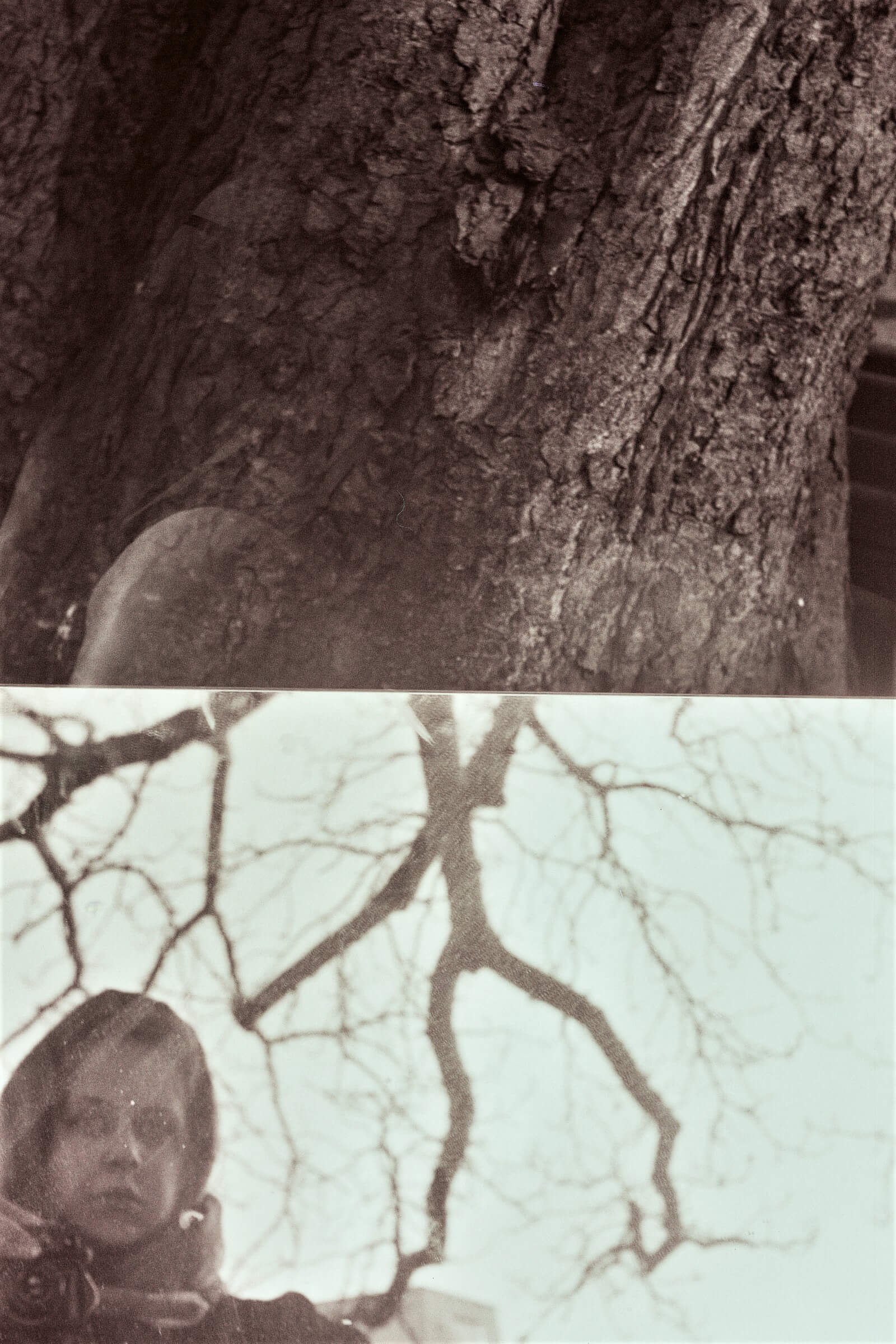

I was raised in Shostka, a city in northern Ukraine situated around 60 km from the Russian border. The factory producing Svema cine-, photographic, and X-ray film was formerly located there. This factory provided jobs for some fifteen thousand individuals, which accounted for about a third of the town’s population. My grandmother was one of the workers and was employed as a magnetic tape cutter. I never got the chance to meet my grandfather, but I know he was passionate about photography. He was fascinated by cameras from that time and had a Sokol, Zenit, and Lubitel. He was skilled in chemistry and had set up a lab in his kitchen for developing and printing. He captured his family’s life during the 1960s and 1970s in Shostka, Novhorod-Siverskyi, and the nearby village where some of his family resided. He contributed extensively to the family archive.

Photography was a regular part of my mother’s life – she inherited a Zenit camera from her father. From an early age, she snapped photographs of her friends, during vacations and trips down south, and whenever she fancied it. Now I have this camera. I’ve taken the majority of my film photos with it.

During my teenage years, photography often served as a way for me to spend time with a cherished friend and to explore my own growth. Through this process, I may have been attempting to make the space of a despondent city, once an industrial centre, more aesthetically pleasing, while also depicting the challenging stages of adolescent separation, individualisation, and denial. The rebellion of a daughter and the indulgence in extremes.

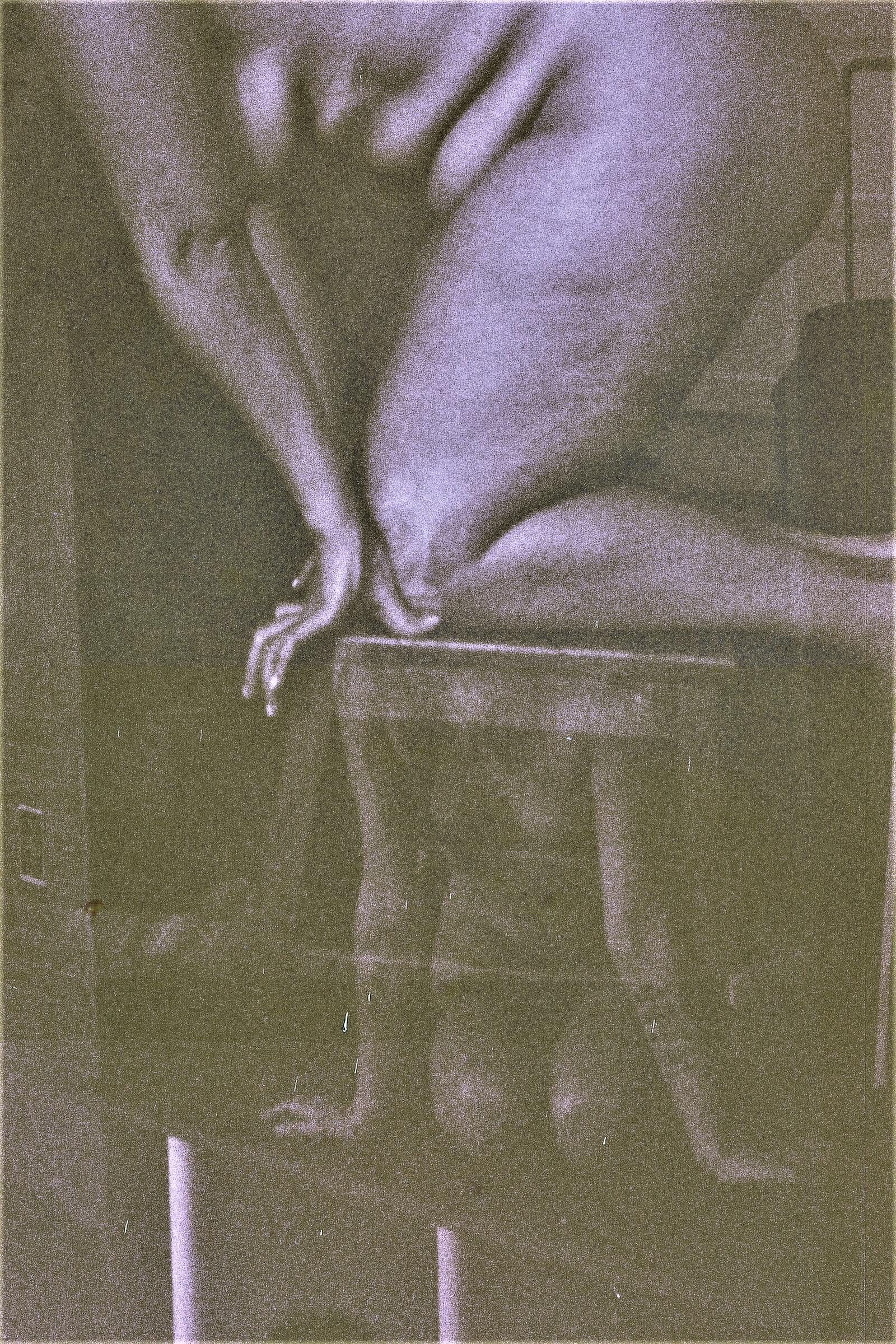

Shostka, 2014. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

My friend and I explored the run-down areas of Svema and Khimreactiv plants and other industrial sites, capturing photographs with various devices, including phones and film cameras.

Shostka, 2014. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

When I review these photos, I realise that we were creating our own town in our hearts, in a conversation that only we could comprehend. I recollect the town where I spent my youth with great tenderness.

Shostka, 2014. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

At first, I was drawn to the old-fashioned style inspired by Greek traditions: excessive mannerism, free love and leisure. I admired the works of Julia Margaret Cameron, Alfred Stieglitz, and later Francesca Woodman, Irina Ionesco, and Nan Goldin. When I was fifteen, I was really moved by Goldin’s collection The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. And right around the same time, I read Orlando by Virginia Woolf and Paradoxia by Lydia Lunch. Premodern meets nihilistic post-punk, and the differences merge perfectly. I felt like I was encompassed in my own sadness and the luxury of extremes.

Shostka, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Why film photography?

Zenit was my only camera for a long time. Recently, I bought an old Canon and Olympus. Last winter, I got an Instax as a gift.

Odesa, 2020. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Film photography limits the number of frames you can use, making it less consumerist, and encourages patience. This mindset assists in identifying significant images. Besides, film, its development, and scanning are costly, which is another constraint. Nonetheless, I duplicate pictures as a safety measure.

Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

The film encapsulates the photograph, multiplying the effect of nostalgia, and is a material prosthesis of memory that is a support structure for us in the world.

On nostalgia

Every time a picture is taken, I know that I will miss this moment in the future. I feel a premature nostalgia and sadness, and I know that nostalgia is expected in the future. It is an interesting phenomenon of pain circulation.

Lviv, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Photography is a balance between what I see and what I capture. I sometimes regret my photographs because I wish I had taken them differently. However, this is a lie – there was no other option, I was myself, and we were ourselves. As a photograph becomes the past, it gains some intriguing treat. The further back the history, the stronger the sensation.

Lviv, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Kotelva, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Links with the Ukrainian history of photography

I sometimes exhibit my work and publish it through DIY publications. My photos are the practice of living. I appreciate the opportunity for exposure.

I discovered Ukrainian photographic history later than any other but have great respect for it. I particularly enjoy the creations of Oleksandr Chekmenov and Borys Mykhailov. I am also fond of Vil Furgalo.

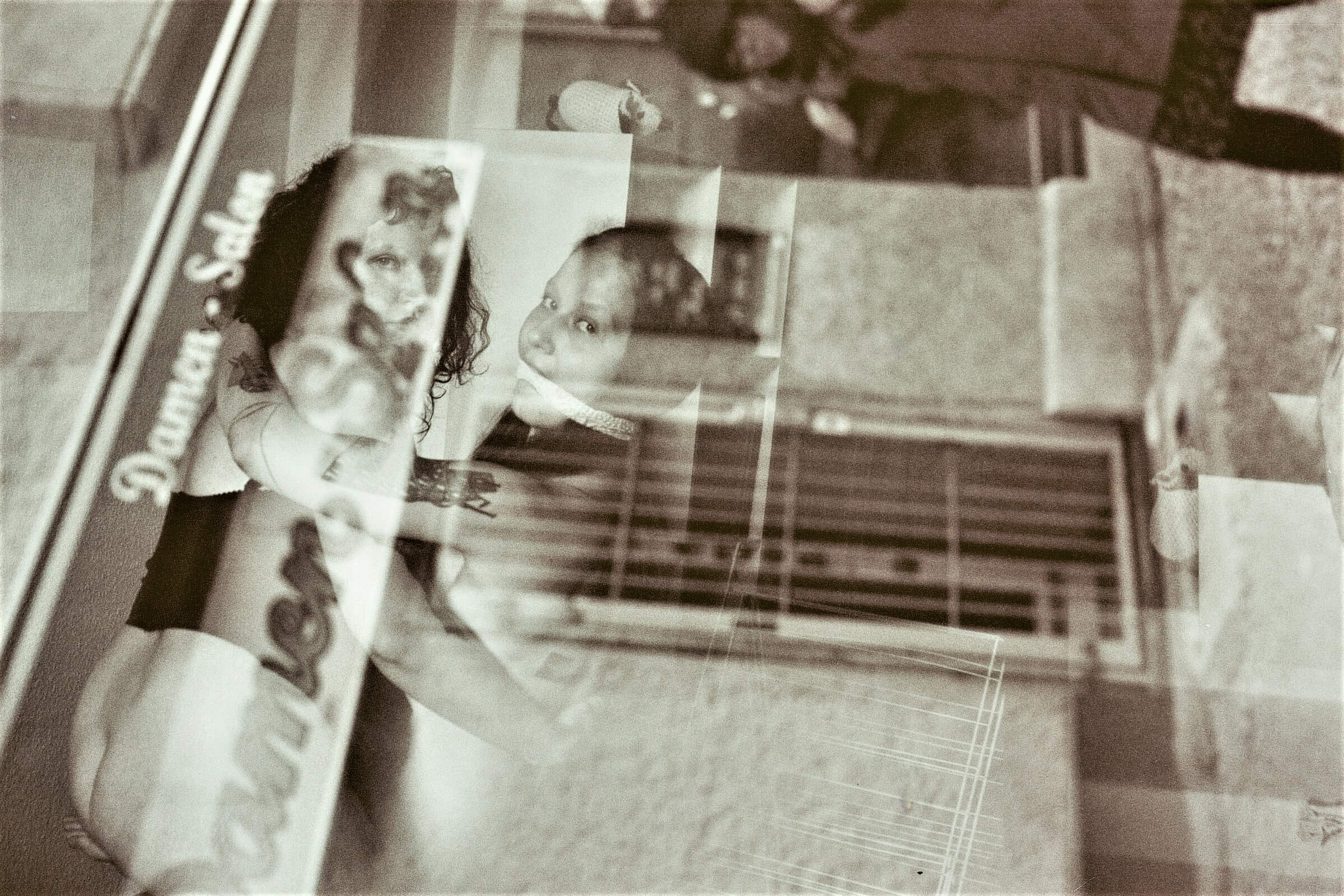

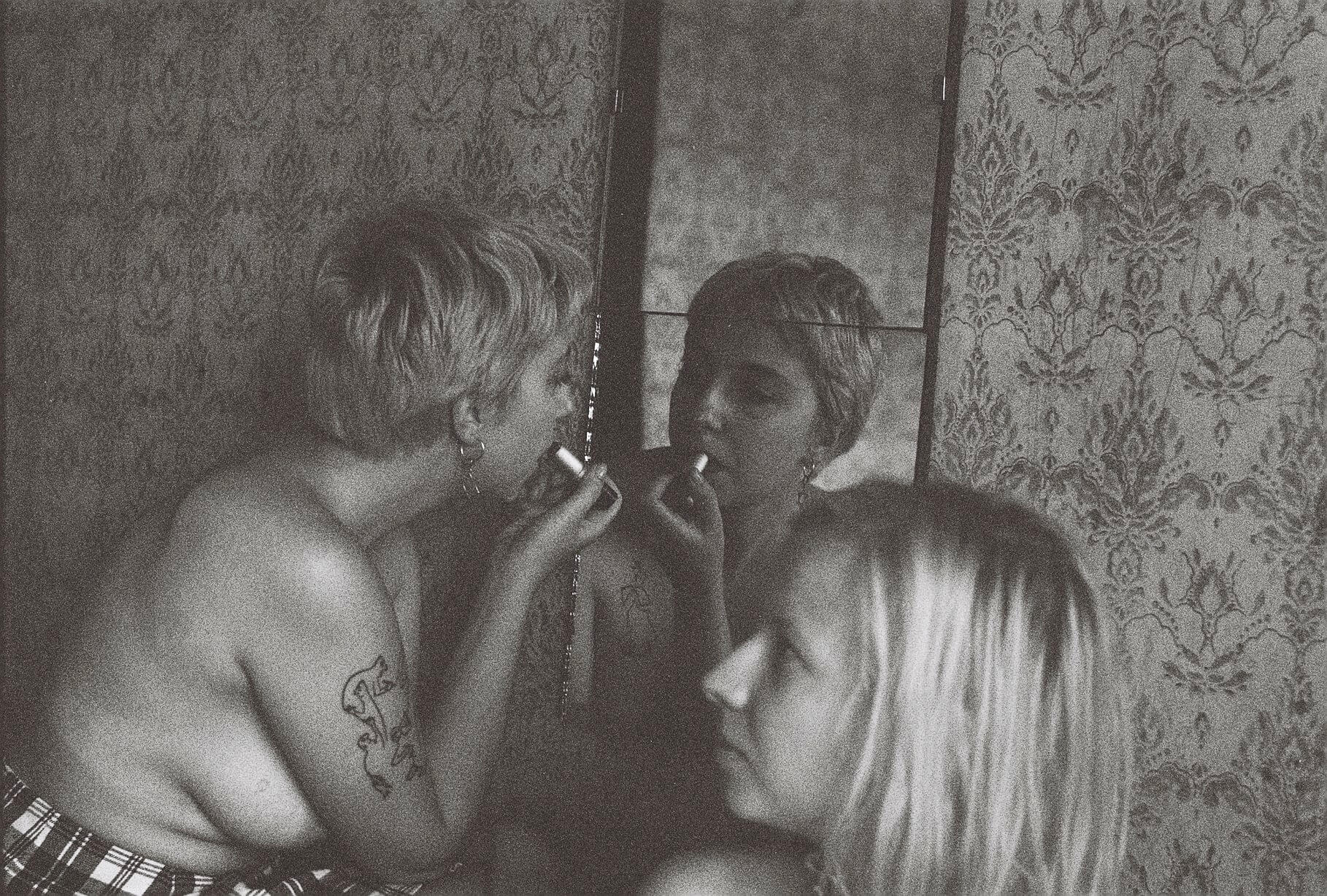

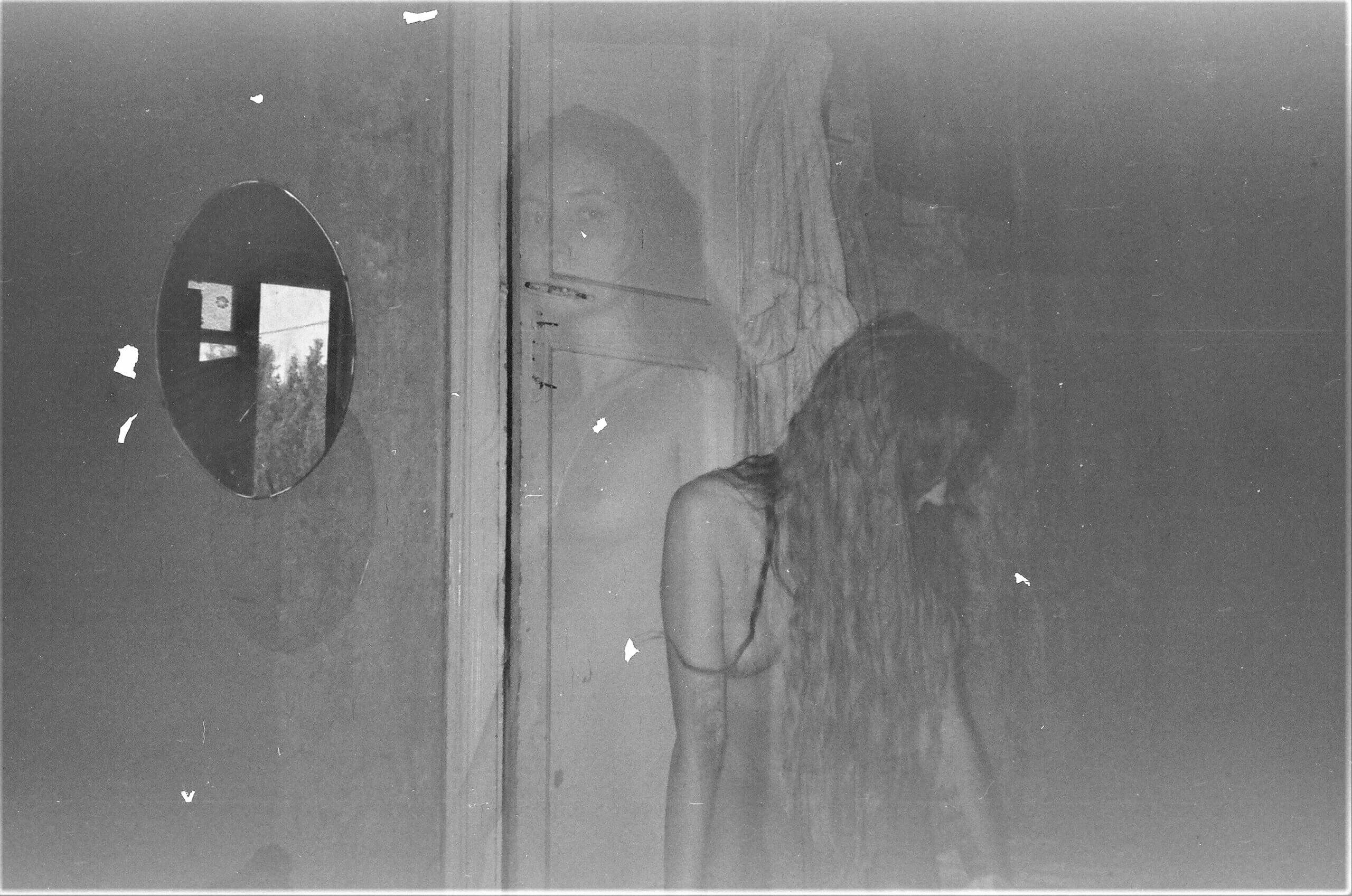

Lviv holds a special place in my heart as it is where many of my loved ones reside. I lived there during the year preceding the large-scale invasion. My life was quite unconventional during this time, filled with passion and love. We used to gather at home, drink wine, and snap photos of each other. The private became public and vice versa. Those were carefree days of intense emotions and great beauty. I still miss those times.

Kyiv, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Lviv, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

I was in Shostka when the large-scale war began; at the end of March I reached Lviv.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

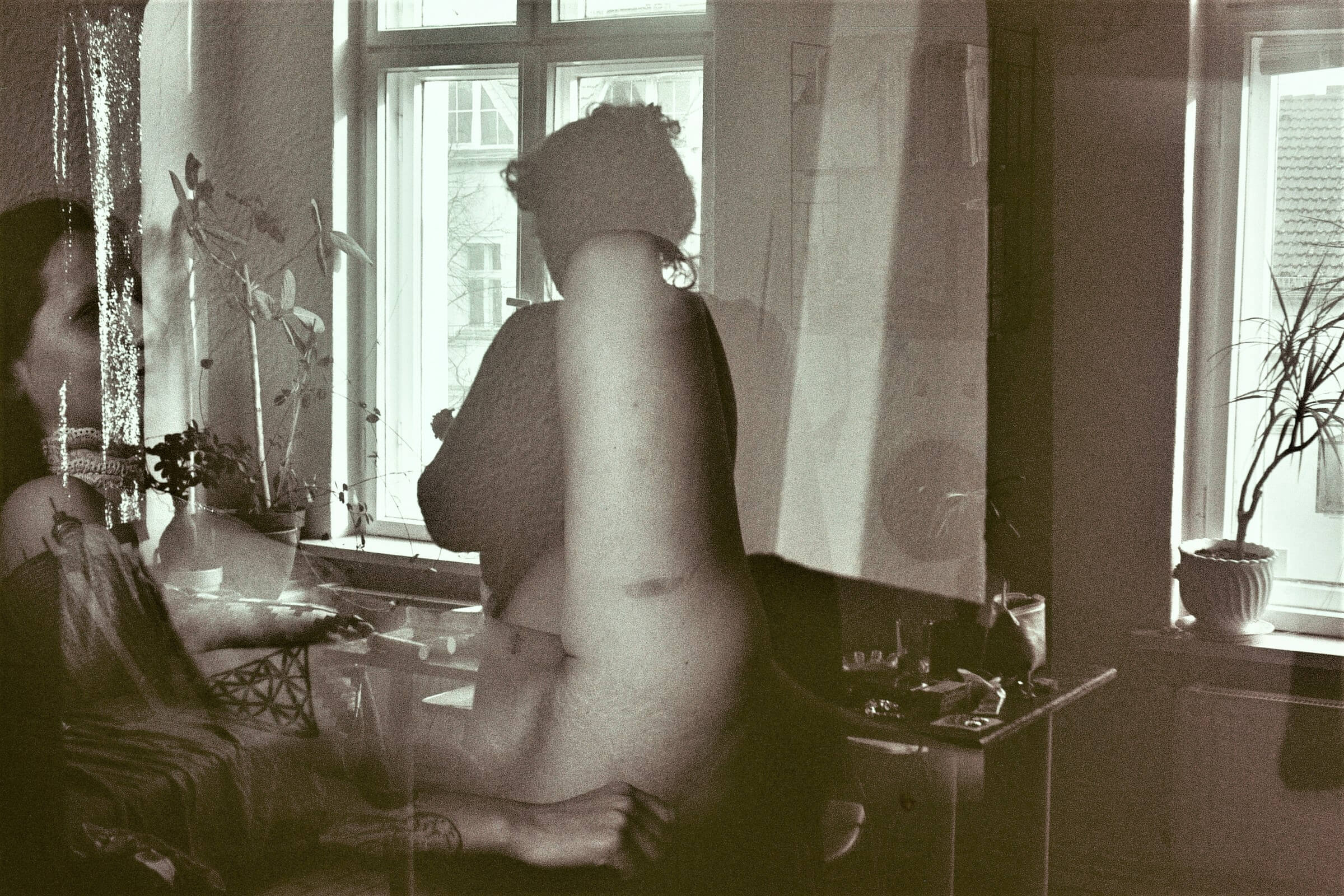

The flats in the city were overcrowded, so I shared a room with my photographer friends, Anya Nykytiuk and Hleb Yashchenko. Four other internally displaced people from the north occupied the next room. Whatever we did was somewhat public, whether we intended it or not. We photographed and filmed each other a lot. Sometimes, my wife stayed over. We had breakfast, bathed, slept, and made love together.

At the end of June, we gathered all the footage we filmed in the spring and organised an exhibition in our flat titled We Lived.

Photo from the We Lived series, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Then I moved to Germany for financial and personal reasons, where I had to work a lot more. I’m a professional editor, I shoot photos less frequently now, and I can’t indulge as often in enjoyable activities.

Berlin, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Experience of emigration

The need to emigrate worsened the crisis that the war caused in my life. Depression descended upon me, my parents’ health deteriorated, and our economic status became more unstable. I felt lost and disconnected from my prior self as every aspect of my life was thrown into disarray. To become stronger, I had to rediscover myself and my way of living. Luckily, photography provided an opportunity to explore the city, myself and others. It can facilitate a connection with yourself or someone else, creating a pleasant memory of a specific place in an unknown country.

Berlin, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Turning a foreign space into your own is especially important during moments when you feel like the environment has no recollection of your existence, that it is not about you. Initially, I only photographed my close friends during their brief visits since I had no one else to shoot.

Berlin, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

In times of war when life and memories are constantly destroyed, the desire to capture the faces and moments of loved ones intensifies. Now I take many pictures of my family, taking plenty of “memento photos”. In the future, I would like to become skilled in documentary photography and also learn the complete process of analogue photography.

Photography as a way to explore and remember

I take pictures frequently, of myself, objects, and houses. At some stage, I realised that I was extremely scared of not existing, I was persistent in exposing my presence. I fear forgetting or losing something.

I enjoy sharing my perception of someone’s personality, giving, and creating play spaces. There is a certain sense of power and enjoyment in it.

Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

I think photography is the way I talk to people – “the grammar of seeing”, in Susan Sontag’s terms. Photography helps me confirm myself and others as present and acknowledge my experience of being alive. This is always the result of trying to hold on to sensuality, which prefers to weather away, to dissolve in time. It is also the effect of creating your own ideal version of Lesbos and capturing it in great detail.

Bila Tserkva, 2020. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

My closest friend and critic, Dana Kavelina, frequently states that my images possess a distinct temporal reference. Occasionally, they are indistinguishable from the time they relate to, or they disregard it altogether. The images often narrate a story about time – a time for intimacy, for synchronisation, or a time for joyful idleness that knows no bounds.

Portrait of Dana Kavelina, 2020. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Dana Kavelina, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

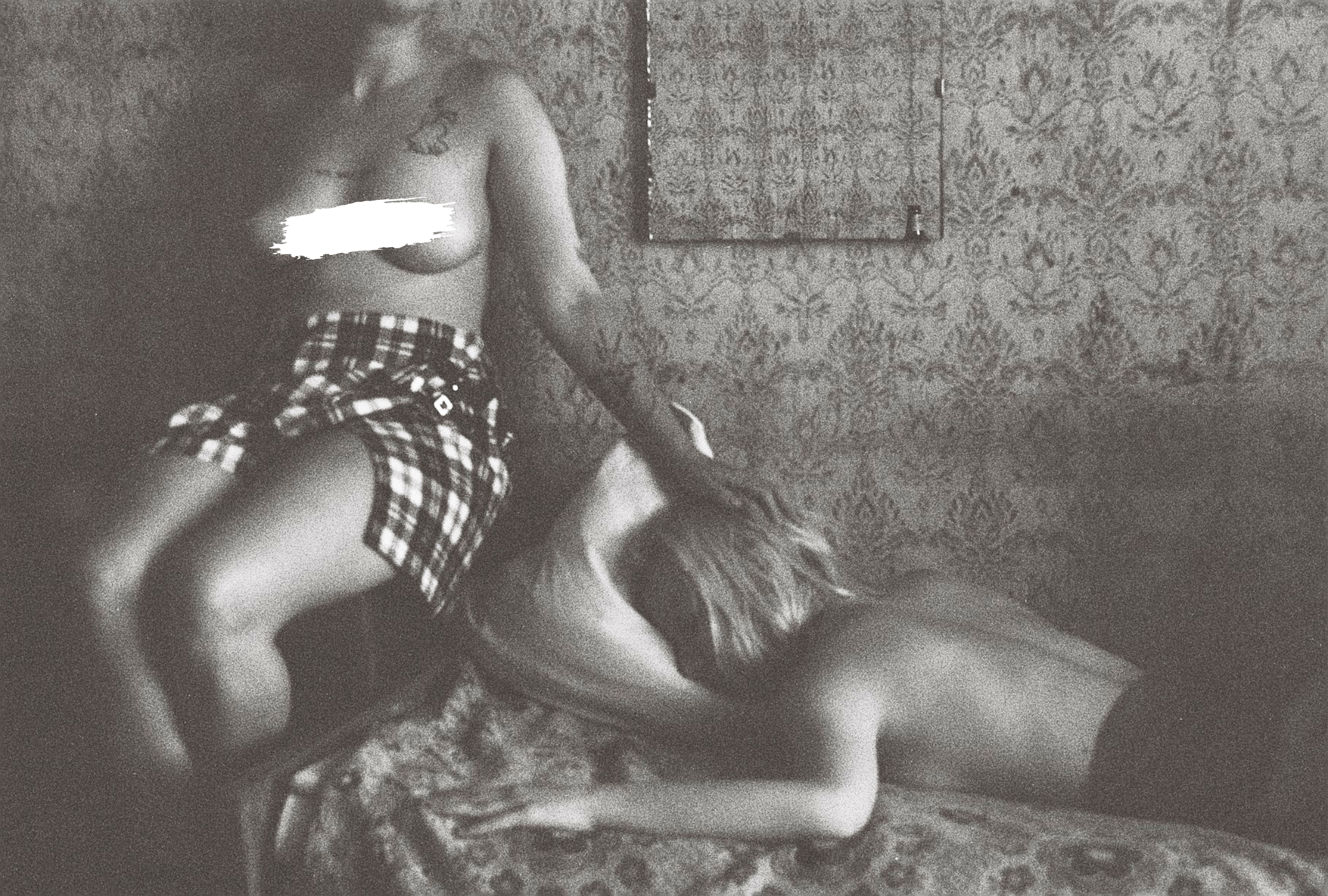

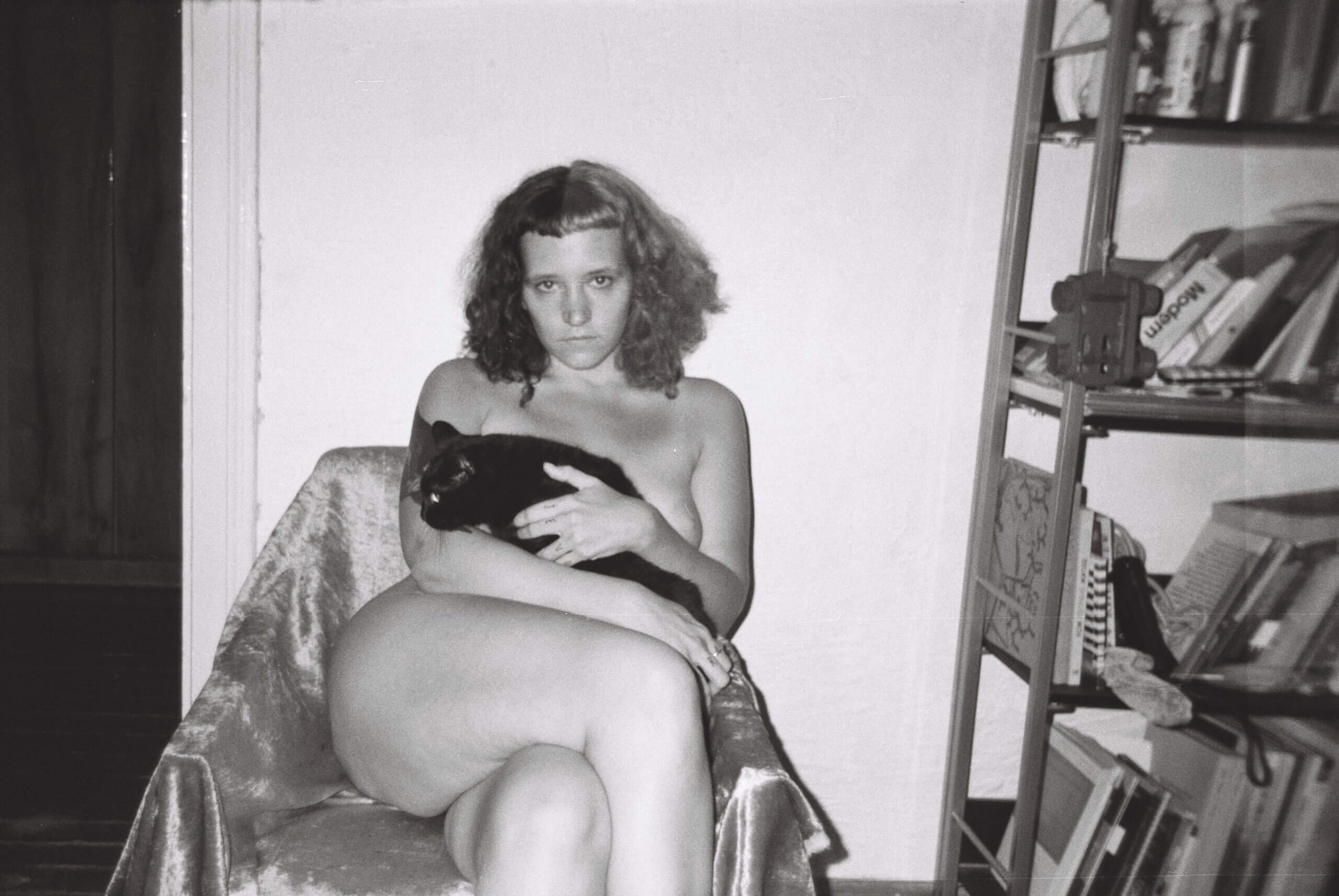

When I invite someone for a shoot, I suggest we pause and make a shared female* space for enjoyment amid the mundane. We can fashion a new body and create an image from it. We can embrace the state of non-action. We can become an object of love.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

The story of creating portraits and choosing models

I think all my photos are about love. I tend to take pictures of people who are either very close to me or who I like. This is a significant factor: taking a photo is a ritual of expressing emotions and declaring my love for the collective image of the Beloved.

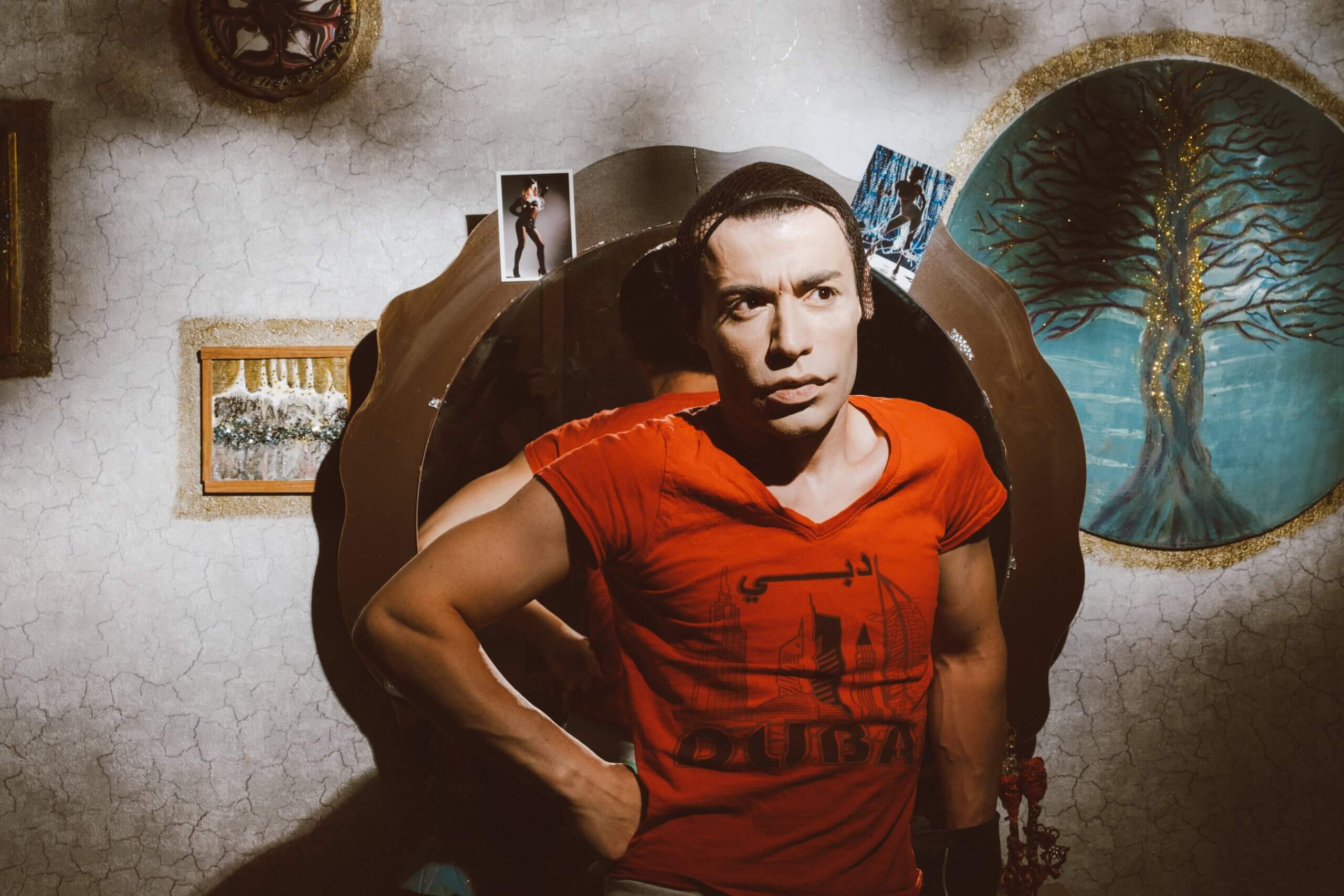

Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

In a letter discussing my photos, Mykyta Kadan mentioned how the emotions felt towards the person in the photo serve as a path to appreciating the photo itself. It is like the intimate pays back the artistic. It’s a reciprocal relationship between the photographer’s affectionate lens and the viewer’s affectionate gaze, both focused on the person captured in the image. It’s like they didn’t meet each other, only the person in the picture, and their meeting was unplanned and unsettling.

Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

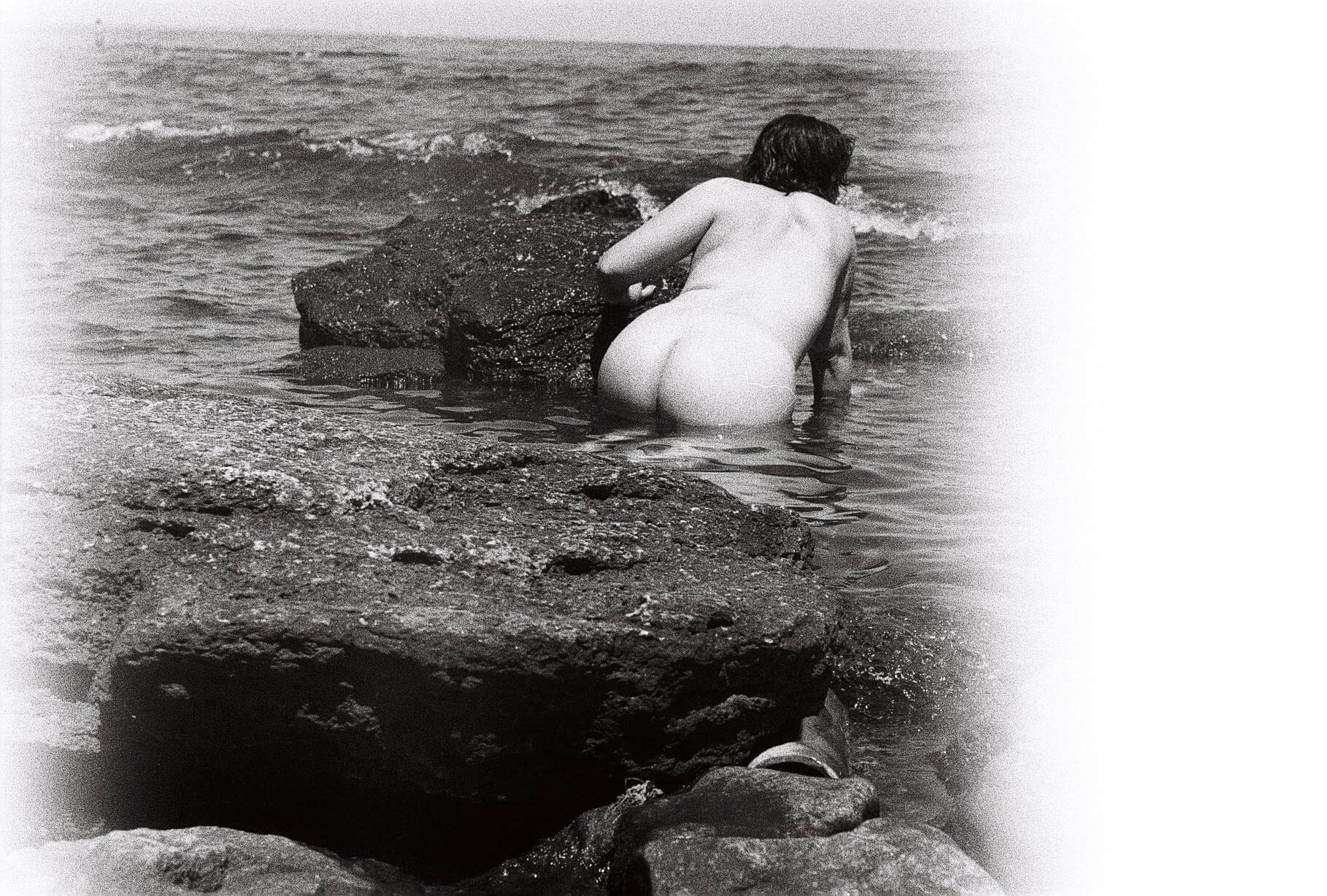

Usually, taking photos happens naturally and without planning. I ask if the person would like to have a photo taken and then ask if they would like to remove any clothing for the photo. I then act on their answer, giving certain clothing and objects more importance. This practice always seems to carry a promise, which can be seductive, but everyone knows the promise will not be fulfilled, making the photos somewhat melancholic.

Bila Tserkva, 2020. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Researcher Zhanna Dolgova defines seduction as a type of “nurturing assistance to another woman,” a “hidden, elevated female sensual challenge” that allows one to “unleash a different aspect of oneself for oneself.” This reminds me of Germaine Krull’s photography, particularly the erotic series with lesbian content called Girlfriends. The models exist in the time and space of the studio, and their gazes are directed towards each other, rather than inviting us to join in.

If we are very close, I just pick up the camera and take a picture. In the past, I would stage the shots more often. Nowadays, I favour a more vernacular language.

Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

When I require particular models for particular photography ideas, I post on social media and ask people to share the call outs. Typically, the individuals that sign up are distantly acquainted with me.

Ways to find inspiration

I am inspired by others and fortunate to be loved by beautiful women*.

A crucial source of inspiration for me is my emotional, intellectual and creative union with Dana Kavelina. We engage in a continuous dialogue, which generates conjectures, queries and solutions about the things we do. I frequently assist with her films, and collaborating with her enhances my growth as an artist and producer. I have created the most portraits of her.

Lviv, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

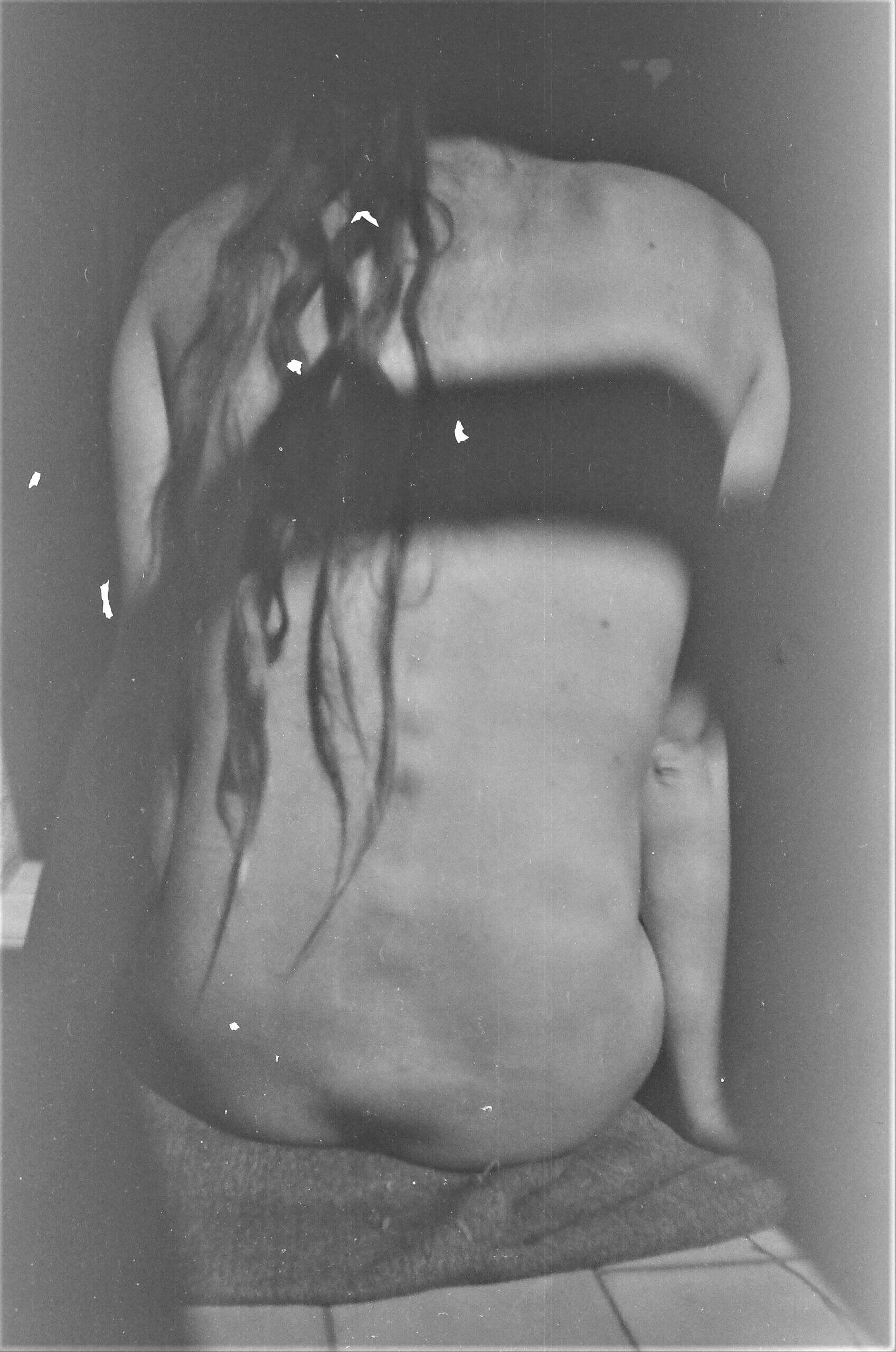

I feel pleased to create a space for healing others through photography. When people admit that being photographed was a therapeutic experience for them. Being undressed and standing naked in front of the camera has significant meanings related to one’s relationship with the body, its history, presence, dynamics and dysphoria.

Lviv, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

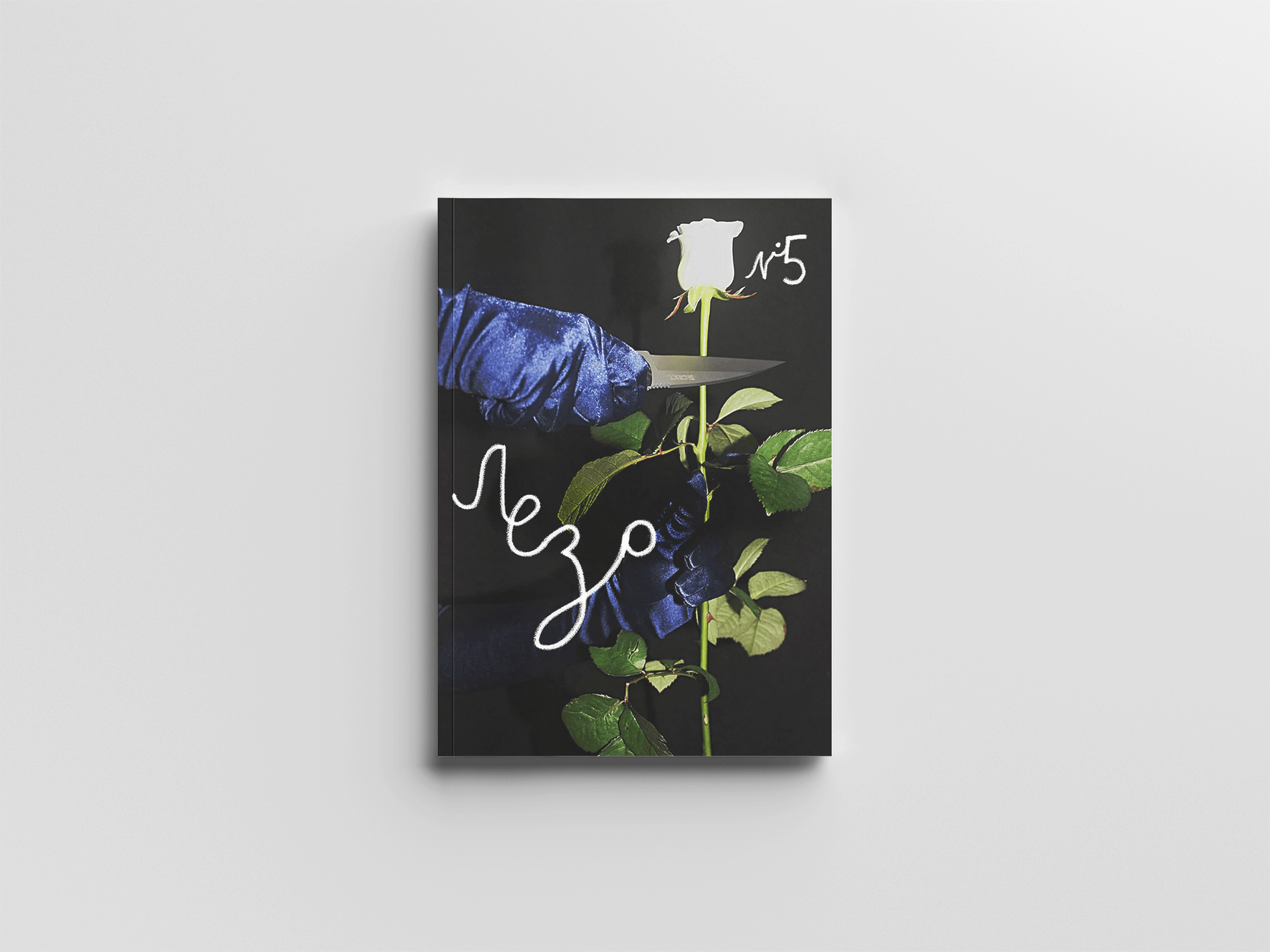

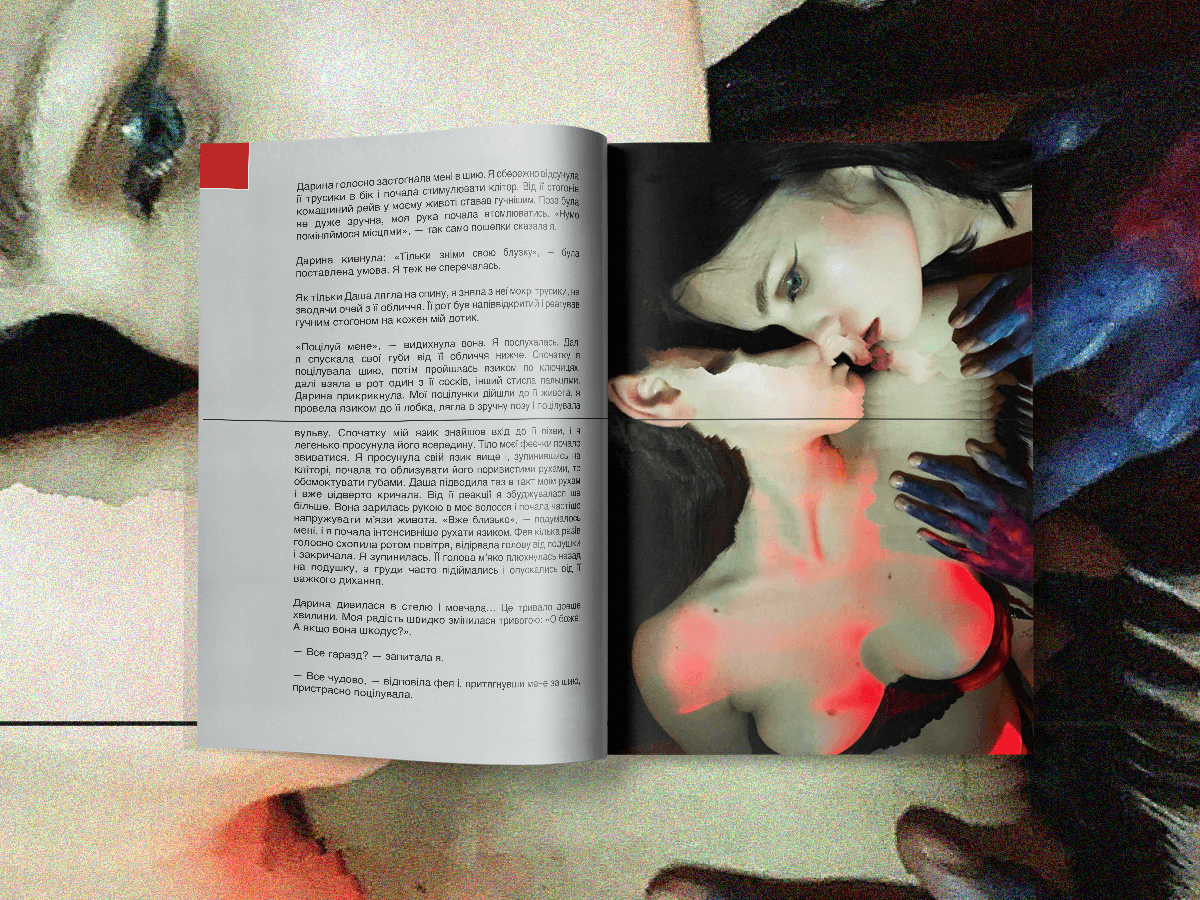

In 2020, Kateryna Semchuk, the editor of the Ukrainian lesbian indie publishing company Lezo, proposed adding my photographs to the fifth edition of the magazine. This was a highly sensitive and crucial form of communication. Some persons had never posed nude before, whilst others had traumatic psychosexual experiences. With most people, we would talk before starting the process. Sometimes, the women* and non-binary people got to know each other and exchanged phone numbers.

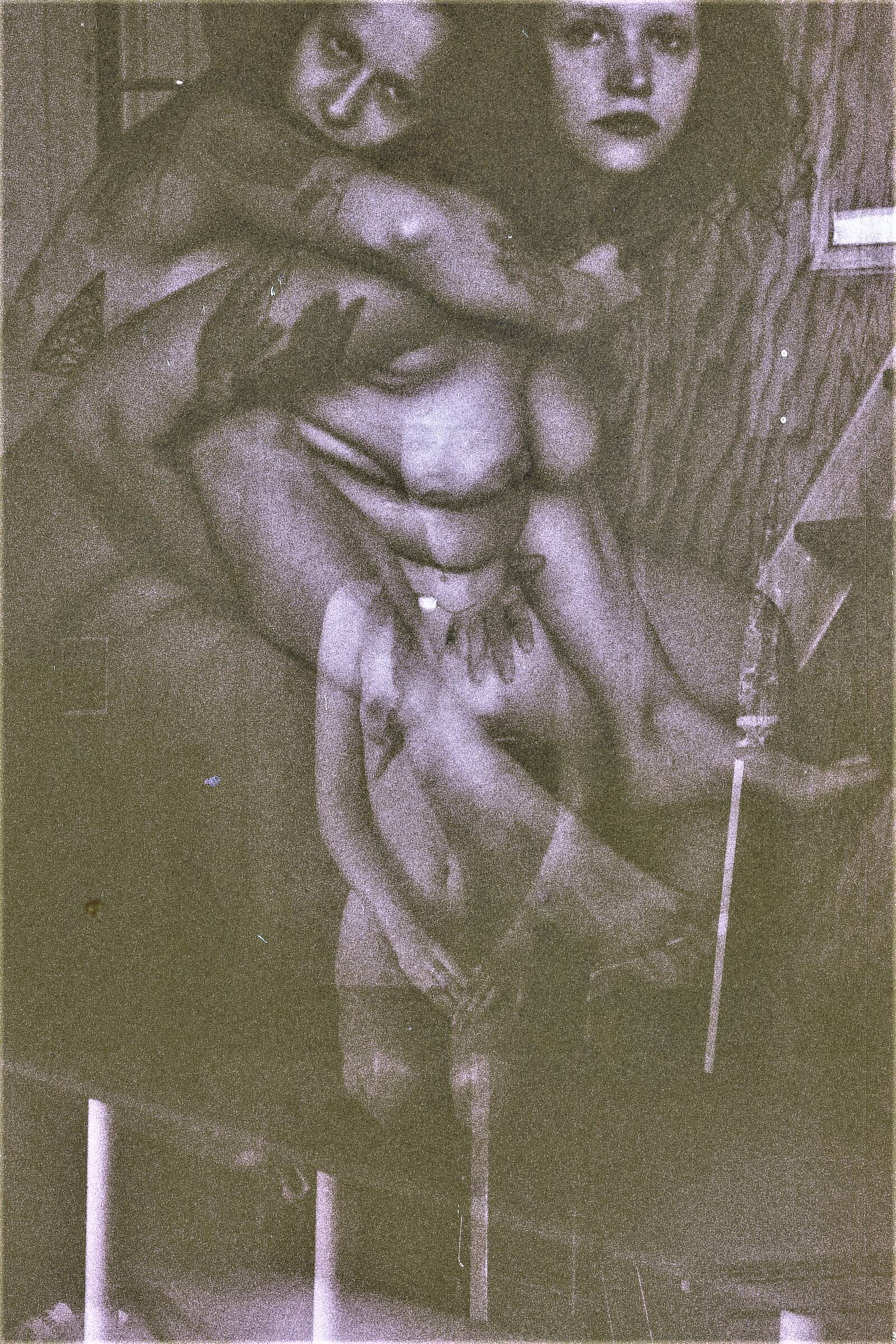

The Half-Life Waltz series portrays dysphoria, fragmentation, and the loss of integrity – both physical and emotional. Additionally, it portrays the disintegration that can occur when one meets another, from a sapphic perspective.

Photo from the Half-Life Waltz series for the DIY magazine Lezo. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

A year later, Dana and I received an invitation to join the Poltava project “Garden after the Gods”, a two-day event connected to the garden at the current Poltava Gravimetric Observatory site. Between 1907 and 1915, this garden served as a place for the Garden of Gods creative and philosophical society’s activities, which included numerous artists: Ivan Myasoedov, Vsevolod Maksymovych, Fedir Krychevsky, and Solomon Rosenbaum. They created tableaux vivants based on ancient motifs that left out nearly all women’s* names. Our task was to recreate them from a non-male perspective. We then resolved to “attempt to retrieve images from the historical void, whose glow has been frequently disregarded while creating sky charts”. The women’s* characters with stories involving emancipatory potential were extracted from ancient Greek mythology.

Philomela was sexually assaulted by her sister Procne’s husband and had her tongue removed to prevent speaking of the incident. She turned into a bird to evade prosecution.

Photo from the Photometric Paradox series created within the “Garden after the Gods” project. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

Clytemnestra married King Agamemnon of Mycenae after he murdered her husband and child. When the king was away, she cheated on him and then murdered him and his lover. She is often depicted with a snake as she had a dream before she died that a snake had bitten her breast.

The representation of Lysistrata comes from Aristophanes’ amusing play and stands for a “conqueror of the military”. The story is about women from Athens who, during a military mission in Sicily, reject the advances of men to persuade them to end the war.

A woman named Poppaea, who was Emperor Nero’s second wife, played an important role in making political decisions. She assisted in rescuing Jewish high priests from captivity by the Judea procurator and convinced Nero to prohibit the tearing down of the wall surrounding the temple in Jerusalem.

I asked a group of women to participate in a photo shoot titled Photometric Paradox where we used their bodies to form new constellations. We met in the garden over three early mornings and recreated Antigone, Clytemnestra, Lysistrata, Hermaphrodite, Medea and other empowering characters under the old apple trees. Dana then painted over the photos. When I asked for permission to use the photos in this article, one of the women who participated in the photo shoot mentioned that it encouraged her to seek therapy. This feedback is invaluable to me.

Odesa, 2021. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

A queer view of culture and photography

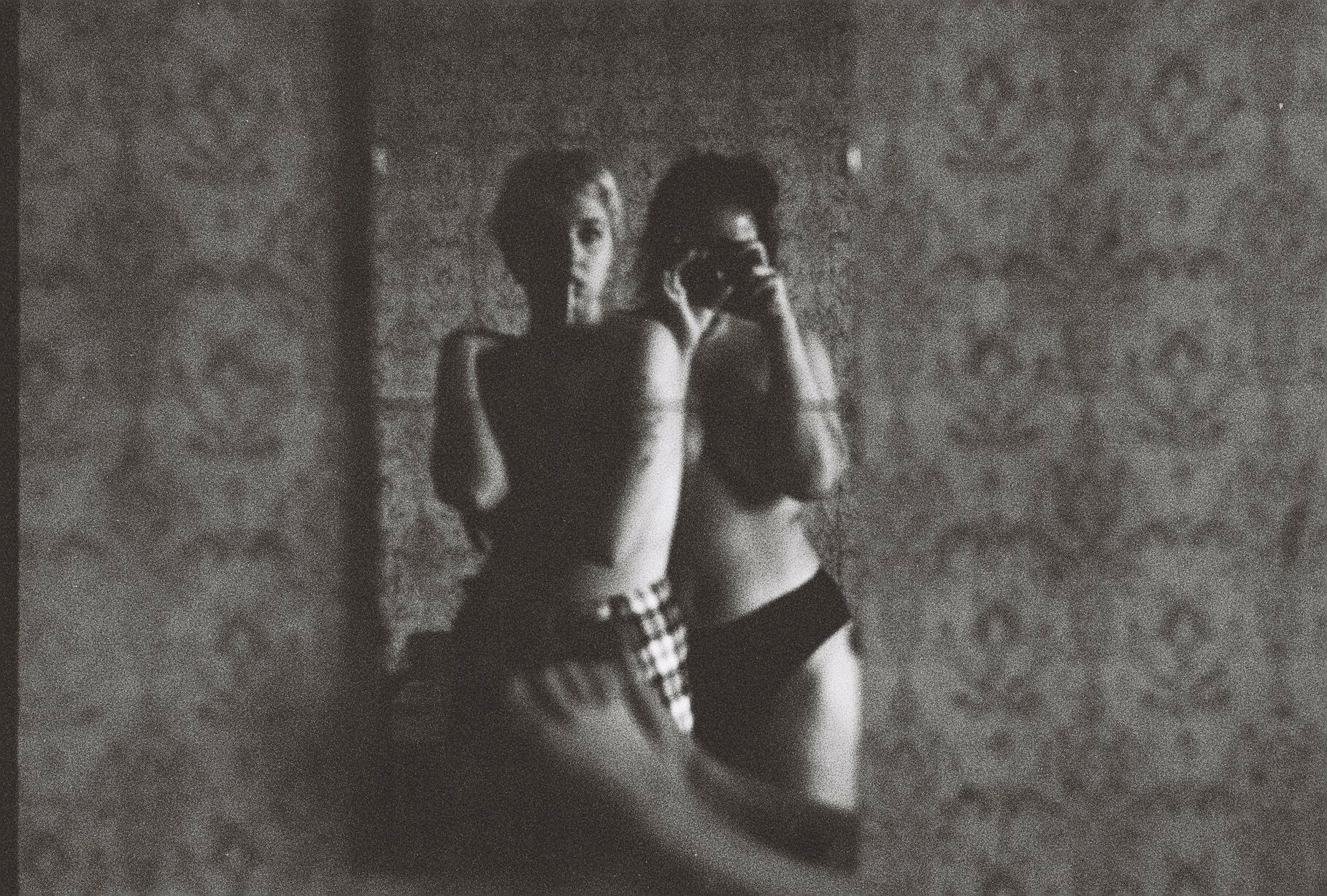

I believe that the queer perspective in photography reimagines the hierarchy line and the struggle between subject and object relationships: we are primarily presented as objects to each other. This is where I discover freedom.

Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

The idea of cyberfeminism defines queerness in a way that I understand best. It highlights the changing limits of meaning and sensuality and the transcendent deconstruction. In my conversation with Dana, we both agree that queer perspectives reveal the manifoldness and elusiveness of a subject. They show how everything is interconnected, how obscenely mutable the world is, and how this mutability is breaking down the rigid boundaries imposed by identity. Queer perspectives emphasise the unity of life and death, the natural and the human, the female and the plantal, and more.

Portrait of the author. Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Katherina Turenko.

In my case, photography is a way to explore my own sapphism and to capture the corporality through my camera lens. I consider my camera to be the Venus’ mirror that helps me to explore myself. And others.

How belonging to the queer community affects art

I have found that relationships between individuals who were socialised as a female can often have homoerotic undertones, and this is something that I contemplate frequently. My work and life are based on the relationships I have with people around me. They are my main source of inspiration and material.

My advice to an up-and-coming queer photographer would be: Discover your own point of tension and pleasure. Trust both.

Edited by Inha Daraselia

Translated by Valeria Khotsina

The original article was published here (in Ukrainian).

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Behind the Mask: Contemporary Drag Culture in Kazakhstan

Chemo Dao

Queer Self-Expression in Kyrgyzstan: Between Cultural Norms and Personal Values

Three Stories from Moldova: Drag, Cinema, Literature

Drag in Armenia: An Evolution of the Artform

Guess the Fact – Queer Artist Edition

Colourful Petals

Emotions. Feelings. Uzbekistan

Peculiarities of Running LGBTQ Spaces in Kazakhstan