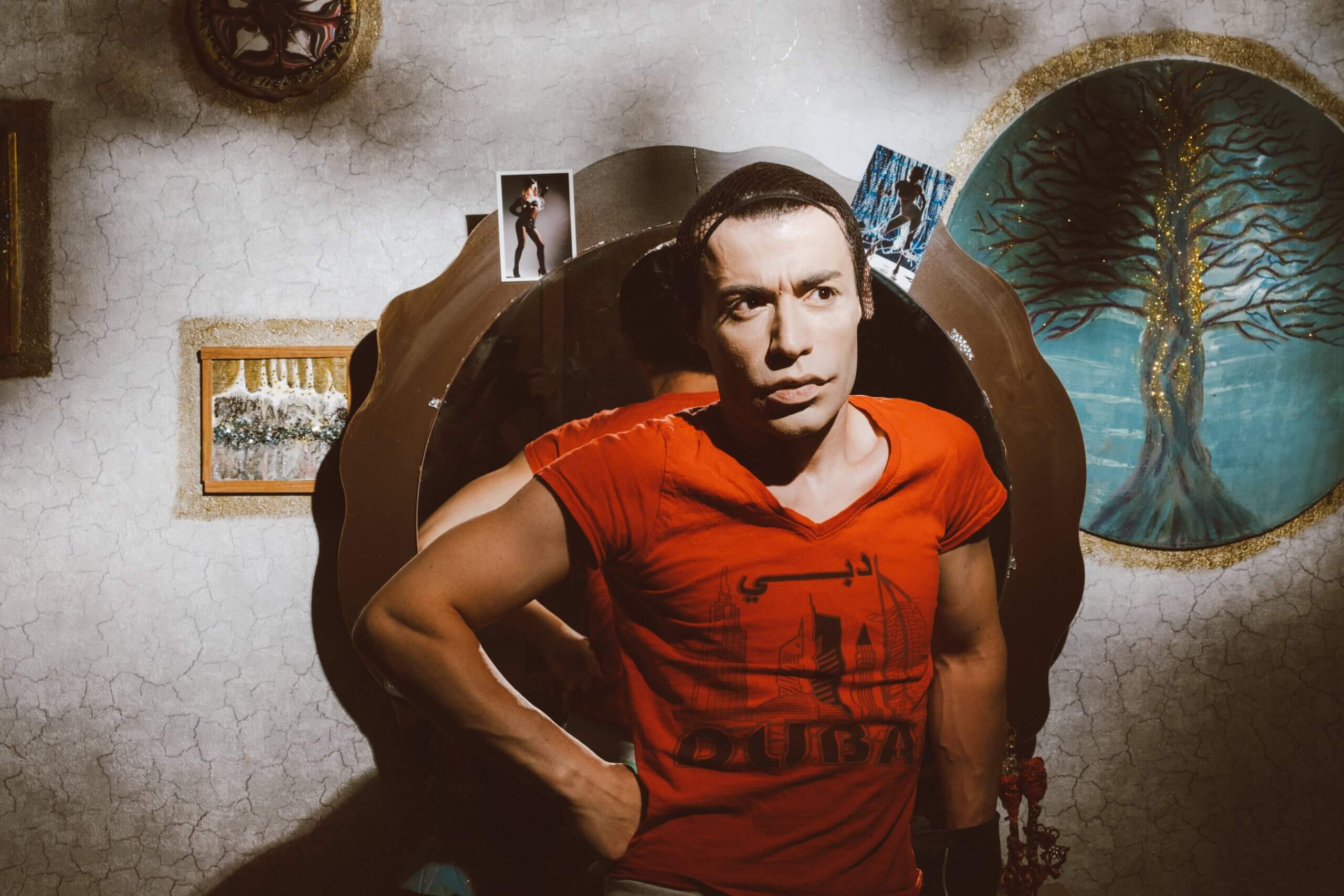

Colourful Petals

Let’s agree on the following: Everything that is called fantasy in this text should remain fantasy. The rest is up to you.

I started writing poems as a university freshman: short, rhymed, love-related. They were addressed to a girl. I was seventeen and only just starting to understand and accept my sexuality. I had found myself attracted to and interested solely in males for quite some time by then. I wrote poems about imaginary love for a girl while envisioning a guy with dark hair and captivating eyes. He would never address me as Artusha.

I studied at the Philology Department — surrounded by the endless recommended reading lists and girls. I could encounter other boys at interdepartmental lectures, which made studying economics more enjoyable but still challenging.

Here, in the classroom, love between men seemed more realistic — here they are, sitting a few rows away from me — than in all Belarusian, Ukrainian, Polish and other literary works. At least in the books we were supposed to read and also based on how they were presented. In those books, men only loved women. Those men, some of whom were attractive and some were not, kind of rejected me by choosing women.

I didn’t understand at the time why I couldn’t find any kind of love “scheme” in the literature that would be relatable for me. Real men — okay, boys — in 2007-2008 were just as beyond the reach as classic literature characters. To be honest, I was improbable to have been enamoured by the imaginary figures devised by other authors. Word!

I created my own male figures through poetry. Men who didn’t choose between me and someone else, didn’t spend ages travelling somewhere, didn’t fight ceaselessly, and didn’t declare their love. They smoked, felt too ashamed to hold someone’s hand, performed a “masculine” part, ignored messages, and failed to attend a rendezvous under the “screen” at Savetskaya Square.

Some time later, the feminine endings in my poems gave way to neutral ones. This way, I guess, I started resisting and winning back space for my male characters.

It was possible to read those poems at different uni events and poetry slams without lying, just keeping things back. I was creating some mysteries, abundant in both traditional and contemporary Belarusian literature.

And then I thought: what if Maksim Bahdanovich’s love poems were not addressed to women? What if Arkadź Kulašoǔ’s Alesya was actually Ales?

(If nobody has considered it yet, I am willing to establish Bahdanovich as a queer symbol, regardless of how unusual or pretentious it may seem).

How much is unsaid, undisclosed, and unread in Belarusian literature? When I consider delving into old Belarusian poetry with a queer perspective, I feel a surge of curiosity tingling my skin, while my palms get sweaty with fear.

What if there was no queer poetry before us? What if I’m reading poetry wrong? What definition of the term “queer” should be used when referring to “that” literature?

Well, let’s put aside the definition of “queer” for now, as it’s not crucial here. (Although as I write this text, I am increasingly convinced that “queer” pertains more to literature produced by queer persons). Furthermore, if we have already begun to indulge in fantasies, why not carry on?

In the spring of 2021, my friend Bahdan Khmialnitski arranged a cycling tour exploring locations in Minsk linked to the queer community and its history. At the end of the route, he demonstrated a small brochure by Uladzimir Valodzin “Queer history of Belarus in the second half of the XX century: a preliminary study”. By the way, the word “preliminary” works here well, since it didn’t examine various things that were only touched upon. But I was interested in the fact that the brochure also discussed Belarusian queer writers.

A fantasy? Perhaps. After all, how else can we explain that among the people mentioned is the name of Nasta Kudasava, who is not queer in any way, just like the fact that Bahdanovich dedicated his poems to a man he found attractive. Although, of course, both his Goddess series and the line “It’s autumn on Lesbos today” fit perfectly into lesbian poetry.

Far more captivating is the reference to Yury Humeniuk, a poet from Hrodna, whose homosexuality came to light only following his devastating demise. The poem Pink Dragon is quoted in the brochure. In this work, a pink dragon is contrasted with a woman. It is unknown whether some other man is behind him, or the persona himself:

“Sleep as long as the reflecting body

retains your frosty impression”.

Svetlana Alexievich’s name is also mentioned, as well as the love stories in her unpublished book The Wondrous Deer of the Eternal Hunt.

But when it comes to reality rather than fantasy, the only name mentioned that I absolutely support is Nasta Mantsevich’s. Nasta’s book Birds was published back in 2012 and quite warmly received.

The readers only met the men in my poems in 2017. Quite shy at first, they became more prominent over time. My men viewed the world through the Belarusian language and explored it with touch.

In the book Water Comes Alive, which was referred to as the first collection of gay poetry by Daria Traiden in an interview, queer themes are apparent. The line from the poem Because is straightforward: “Because poetry is him”. For this reason, I want to bring up the Debut prize that the book received. As in the previous year, queer literature was the winner: Daria Traiden received the Debut Prize for the prose book Kristallnacht in 2019. By the way, Krystsina Banduryna was also shortlisted with her book Homo. It appears that the effort to integrate queer literature into the mainstream has been quite prosperous.

After some poetry festival, a young poet approached Krystsina Banduryna and me. He thanked us for our poems and recognised us as promoters of queer literature (poetry).

I pondered it for a while, trying to comprehend something we didn’t even dream of.

Did we want to be among the pioneers and are we really the first? How can someone create queer literature using no historical precedent, especially in poetry? And most importantly: how and where can one find this foundation?

I once talked to the Swedish musician and activist Jan Hammarlund. He talked about Selma Lagerlöf, a remarkable writer whose homosexuality was discovered fifteen years after her death through her letters. This news became a sensation, which is hard to imagine in Sweden. One can have various opinions about a post-mortem outing, but in the long run, Jan believes that such occurrences hold significant importance. I would say this is the very foundation that we, modern queer writers, are trying to find in Belarusian literature.

Why look for it? For one thing, to avoid feeling like the “first” and only one in a vast legacy of heteronormative literature.

There was a time when I was under a great impression of Igor Kon’s book Faces and Masks of Same-Sex Love: Moonlight at Dawn. Especially of the time when Mikhail Kuzmin, the “Friends of Hafiz” society, Sergei Diaghilev, Zinaida Gippius, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Sophia Parnok lived and experienced a sense of freedom. Life and literature that are unrelated to the Belarusian reality.

At this point, I would like to return briefly to Bahdanovich, who published his works in the Yaroslavl newspaper Golos under the pen name Ekaterina Fevralyova. Researchers say the reason for Bahdanovich’s choice of this pseudonym (and the other ones) remains unclear. Yet, it’s important to acknowledge that there is some story behind it. So, if all I have is my imagination, let me dream up alternative versions of Maksim and Magdalena.

And what about Julij Taŭbin? Let’s fantasise.

For instance, Andrei Khadanovich highlights the puzzling lack of love poems in the writer’s poetry. This can be explained by two things. Firstly, Taŭbin was so focused on literature that he ignored everything else. Secondly, during that violent period, not writing about love could be the only option. Also, if you even feel lonely in your own “poetic manner”, you probably have no reasons to share your love — not even through feminine endings.

Take the poem To the Loved One. The poet writes:

“Outside my window, the capital is bustling.

Oh, my friend! Many of you, still unexplored,

Lurk across the fields.

That’s why your image seems so kindred to me”.

For some reason, I can’t stop thinking about the words “lurk” and “many of you” combined with a “kindred image” in one stanza. Maybe because when I was seventeen or eighteen, I had a feeling that there were many of us. Because I had to “lurk” not only in real life but also in my poetry.

I think if someone asked me to describe Belarusian or any queer literary works in a few words, I’d pick the word “lurk”, among others.

For our queer literature, it is relevant to this day. At least because no one has yet discovered someone like Selma Lagerlöf in Belarusian literature. The sturdy ground lies still and is decorated with swaying flowers that occasionally fall and nourish the soil.

On the other hand, I am somewhat comforted by the idea that in fifty years, I expect that there will be no need for such discoveries. After all, queer writers are already creating — petal by petal — a foundation for new flowers. And they, I have no doubt, will definitely come into blossom.

My essay was supposed to end in a fancy way, and there was no reason for it not to happen, but I stumbled upon Alexey Lunev and Sergey Shabokhin’s exhibition, Queer Tracing Paper, and I have to share my findings and observations.

Is Yanka Kupala the wife of Yakub Kolas? This question opened the exhibition of artists who are trying to make sense of the Belarusian queer history and queer archive and rather audaciously play with heteronormativity. The curatorial statement itself read that Yanka Kupala and Yakub Kolas are “both poets, (probably) heteronormative, most likely not a couple, but the idea that this will be a work based on a typo in the names of Belarusian canonical writers has crept into our thoughts”.

On one side, this exhibition aims to demonstrate the progress made in the Belarusian queer community, despite the feeling that there was no one and nothing before us. Therefore, to this day some initiatives do not mind being called “the first”. On the flip side, it’s also the recognition that we have limited knowledge of what occurred before us. Like we are forced to fantasise and overinterpret, piece history together from small conjectures and assumptions.

One important part of the exhibition involves tracing paper, which artists use to explore both global and Belarusian queer history. They aim to find similarities and differences and to identify gaps and unexplored areas.

A fictional queer history meets the genuine queer history, revealing formerly hidden gaps created by decades of colonial and totalitarian erasure and suppression.

But we need to create something more than just an imaginary queer archive. For example, Nasta Mantsevich has been organising around it for a long time. I was fortunate to volunteer at one event she made, and even then I observed the enormity of this genuine collection of Belarusian queer history.

And what about literature? At least, soon we will see the first attempt to archive the anthology of contemporary Belarusian gay literature Boys Are Breaking Loose. Skaryna Publishing House, under the editorship of Uladzislau Harbatski, will be publishing it.

I envision a splendid “Belarus of the Future” where freshman students from the Philology Department, and possibly from other departments, receive reading lists that include queer literature, among other writings. The autumn sun boldly breaks through the huge classroom windows. Someone writes bold poems about love. And nobody cares why a boy tells another boy he loves him, or why a girl kisses another girl.

I imagine fantasy colliding with reality and taking over.

Listen to the podcast-dialogue Queer Literature by Krystsina Banduryna and Artur Kamaroŭski (in Belarusian)

The article was originally published here (in Belarusian)

Illustrations: A. Mur

Translated by Valeria Khotsina

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Behind the Mask: Contemporary Drag Culture in Kazakhstan

Chemo Dao

Queer Self-Expression in Kyrgyzstan: Between Cultural Norms and Personal Values

Three Stories from Moldova: Drag, Cinema, Literature

Drag in Armenia: An Evolution of the Artform

Guess the Fact – Queer Artist Edition

“Discover Your Own Point of Tension and Pleasure. Trust Both”

Emotions. Feelings. Uzbekistan

Peculiarities of Running LGBTQ Spaces in Kazakhstan