A Story of One Migration

My wife, my child, and I have been out of Belarus for almost three years. We applied for political asylum almost a year ago and are still waiting for a decision.

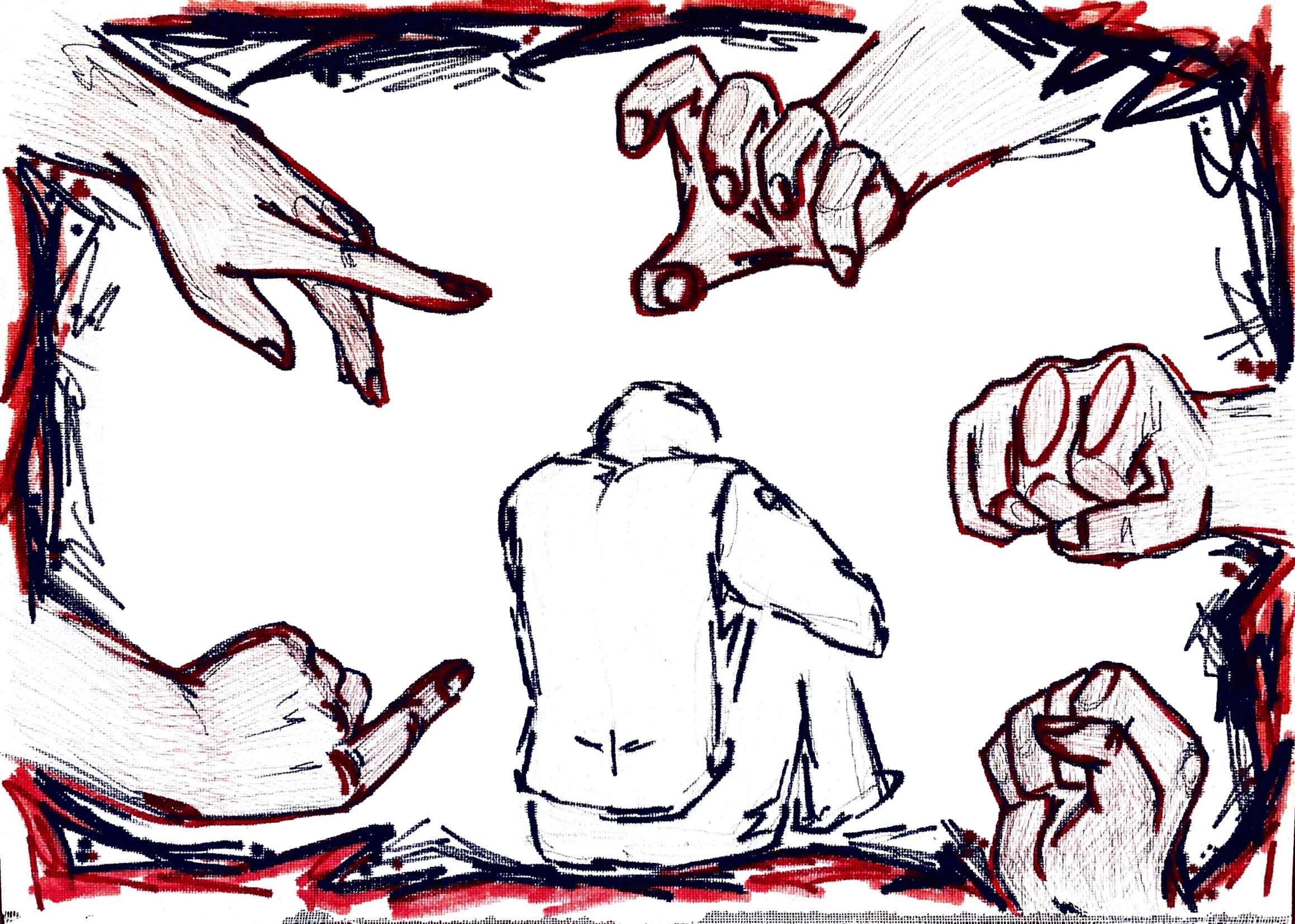

For almost a year we have been living in the “in-between”: between cities and refugee camps, torn between our identities, between vulnerabilities and privileges, across bureaucratic institutions. Among people and their stories. Like a fishing float between waves…

In the international protection system, as in many aspects of life, there is a theory and a practice of humanitarianism. In theory, the system is designed to protect people facing danger to life, freedom, or health. Nominally, it excludes the possibility of economic migration, because in this case there are ‘easier’ ways to regularise one’s stay linked to the level of our usefulness and competitiveness in a foreign market. The god of capitalism has taken care of everything.

From the inside, the international protection system looks like a scene from a horror film, when the main character goes down to the cellar and suddenly discovers a hatch in the floor under a pile of old boxes. In other words, you open the door thinking that this is the basement of your life, only to find dozens of mysterious-looking glass floors below, each having its own rules and laws.

What was once your vulnerability can become currency in this strange grey world. What was once a source of pride or simply a meaningful part of your identity can disappear, be devalued, or become a source of constant stress. All the shells of fantasies about being a good enough person fall off when you realise that the most painful thing you have to say goodbye to is not your home or your passport, but your privileges.

“Cleaning is a good job for you,” K. assures me. К. is an elderly parishioner from a neighboring village. She looks surprisingly vibrant and strong for her age. I can’t help but think that in my country women over seventy look and talk very differently. We had arrived at a meeting organized by a church community for the families of refugees, and during our first small talk, K. asked me what I did for a living. In my country, I had an academic degree, but after a short period of teaching, I worked in the civil sector for almost ten years. “It’s not a profession,” K. is confident, “and one has to sing for her supper”.

I think I’ve heard enough refutations of this worldly wisdom, but I don’t have the heart to say it to someone who pays taxes in a country where my child is fed for free. I also find it hard to explain why these words demean me and devalue my ‘past life’. In general, the term ‘past life’ best describes how I feel in the here and now: like a phantom. As a child, I was very fond of the fantastic theory that some natural objects, because of their crystalline structure, can ‘record’ and reproduce past events, and people living today would consider these ‘projections’ to be phantoms. My whole life is now recorded within the walls of a house I haven’t entered for several years. I think I am still reliving it: through photographs, memories, and conversations. I am recreating projections of a future that will never happen. I am a crystal structure, but for seventy-year-old K., I am a phantom.

The hierarchies we are familiar with — those of race, class, gender, age, and physical or mental impairment — do not disappear in emigration. Their impact on your life goes hand in hand with the declaration of equality for first-world citizens. In a system where you no longer have a passport, you begin to feel the difference between being a citizen and a whole spectrum of legal statuses with limited rights. Vulnerabilities build up in hierarchies and accrue on the familiar patriarchal system like polyps on a shipwreck.

Contrary to my expectations, political conversations in the refugee camp are surprisingly naive. At times like this, I try to lend my political body to my research self.

His predictable ignorance is fair because I don’t know the history of his homeland either. I don’t know when and why the war started there, or which countries sponsored the armaments. I don’t know how his ancestors died or how his family feels about his life in Western Europe. I think about how human beings have been separated and segregated by colonial politicians for centuries, and also about how the modern refugee system that this man went through and that I am going through today is based on a concept of humanism that came out of the European Enlightenment. The same Enlightenment gave birth to the idea of the nation-state and capitalism and made colonial Western thinking the standard of human civilization.

Incidentally, according to the Swedish International Peace Research Institute, my country earned $1.5 billion from arms sales to African countries in the 1990s alone. And my ill-considered and naive ‘ignorance’ of the likely fact that Lukashenka’s officials have been selling assault rifles for years to the people this man’s family was fleeing from, and my education, which makes his arguments about Russia naive to me, are also colonial privileges. There’s something of Schrodinger’s Cat story about existing simultaneously in the symbolic space of post-colonial trauma and white privilege.

It is impossible to draw a unified portrait of a person seeking asylum in EU countries. Victims, adventurers, idealists, trauma survivors, romantics, kapos, people who did not decide to apply for refugee status from a place of informed consent, people whose ability to make informed decisions can be questioned, people who had no choice, and people who consciously chose to be here. Human beings. Esse homo. A sea of human stories expands in front of me. I let them pass through me like waves, I become part of them just like they become part of me. The corpuscular, wave-like, dual nature of this experience is both mesmerizing and depressing.

S. and I go to see her lawyers together — I am there to interpret. I write “lawyers” in plural intentionally: S. signs up for dozens of counseling sessions that she doesn’t attend because of her mental state, and then she reschedules using her children’s phones. I don’t understand the point of these reshuffles, but it’s none of my business. My business is accessible interpreting. In my communication bubble from my previous life, I considered myself a “non-English speaker,” and my conversational level would barely qualify as B1. But our room at the camp is the only one on the floor where adults speak English.

According to the Dublin Protocol, S.’s case is to be examined by another country: the one she came to Germany from and which has already rejected them three times. Today we are going to see another lawyer. As we walk through the grey morning city, S. suddenly tells me that her son was only 14 years old when first interviewed. I try to imagine what someone else’s child is going through in this situation and I want to run back to my room and hug my kid. I feel heartlessly glad that his warm, sleepy, pink little body is still legally an extension of my adult body. At that moment, the fact that of the two mothers, only one of us has the right to him, and the difficulties associated with this, seem to be small and surmountable.

Now S.’s son is almost 18, and her lawyer is trying to make her comfortable with the idea of separate deportation: once he reaches the age of majority, decisions about his status and period of stay will be made separately from his mother. For European security systems, based on colonial notions of humanity, his gender, ethnicity, and religion are an issue. On the way back, S. asks me about the church asylum procedure, and what Protestantism is. “So have they also, I mean, protested?” I tell her about the dogma of the Pope’s sinlessness and the Reformation.

The next time I am taking S.’s daughter to a lawyer. Her mother and sister had to go to a health center — the girl has a documented mental illness. The diagnosis certificate is almost treasured because it protects two family members from deportation at the same time. “You have to decide who will be the guardian of your sister: you or the mother. That person will be able to stay,” the lawyer explains to the girl. I am thinking about how scary it must be to have to make these decisions when you are 19… When I was her age, I could afford to be afraid of other things: coming out to my parents or taking exams. I am also thinking about how sickly ironic it is that stories of escaping authoritarian states are often described as something done ‘for children’s safety’.

The last time I heard about S., I was told that she and her family had been granted church asylum. I never knew S.’s real name — only its Russianised, ‘understandable’ to us version, a colonial legacy of the USSR.

In the morning, a terribly beautiful woman in a security uniform takes us in for a PCR test. “Golden head,” she says in surprise, touching our baby’s hair. “Your baby has a golden head”. I tell her about the Russian poet Yesenin, the “golden head” of Isadora Duncan.

Once we were out of the quarantine zone, the next step was to have a measles vaccination. Several young men from Russia and a fellow Belarusian were also queuing with us. The Russians ask him cheerfully if there is mobilization in Belarus. “It will start soon,” they laughed.

After the quarantine, we lived in a camp block with two families from Belarus. It turned out that the expansion of the Russian-speaking area automatically meant the expansion of the patriarchal agenda. A neighbor teaches a child to shake hands in a ‘manly’ way. In the evening, a woman from the floor came over to ask the other one if she had figured out that we were lesbians and how we had conceived the child. Every day for the following week, I repeated to a grown man that our kid was “not a girl”. “I just forgot”.

By the end of the week, I realized that he was bullying our son in this strange way because he couldn’t be explicitly homophobic to us. Stories circulate about children being “taken from refugee families and given to LGBT couples to raise them”.

Our new neighbors come from Cuba. A young man and his partner, a very beautiful transgender woman. When she walks into a communal dining room full of single men, the room fills with whistling and howling. We don’t go to the dining room for the same reason. We’re sitting in a room on the eighth floor and can’t get enough of the silence after having lived in barracks. Our child is running around the room screaming, but after a room shared with 16 people, it almost sounds like ‘homely comfort’.

The eighth floor has a perfect Wi-Fi connection and just the right morning light for photos — “a TikTok house for refugees”. In the mornings, when everyone is asleep, I lie in bed for a long time, looking at the brand-new plastic unicorn my child left on the windowsill. Lying in bed, having a mattress, and knowing that no one will knock on your door is a great privilege.

In the corridor, I meet the cleaner, a young woman from Ukraine. She warns me to “be careful” because “we have a child and this floor houses queers”. I am one of those, I reply.

At night, the dormitory is evacuated because of a fire alarm. We run down the stairs holding the sleeping kid. We are joined by the crying man, the Cuban beauty, and the cheering boys, the familiar homophobic family from Belarus. I wonder if it was difficult for them to move into the dorm with a floor assigned ‘for these people’… I look up at the black winter sky while listening to the howling of the fire alarms and think of Immanuel Kant. “Two things fill the mind with ever-increasing wonder and awe, the more often and the more intensely the mind of thought is drawn to them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me”.

N. refers to herself as a “gypsy” and to me as a “Russian”. When I ask her if she is familiar with Roma rights organizations in Belarus, she does not understand me on several linguistic levels at the same time. N.’s family is from Mahilou. There, in 2018, the Ministry of Interior raided the settlement and arrested all the men, leaving the women to search for their sons and husbands for a day, only to pick them up all blue and beaten. I tried to find contacts of a Roma human rights organisation I knew for N.: a few years ago I met them at a joint meeting of human rights defenders and Foreign Ministry officials. I found out that the organization was not active anymore. The people who had founded it had moved on to other projects. They were, of course, gadjo.

One day I told N. how after graduation I had worked in a company selling Korean cosmetics for six months, and in a fit of temper I called my former boss a fraud because he asked us to write fake reviews of dietary supplements and shampoos. “I see”, said N. “Our girls would do the same: one sells cosmetics, another sells pots to pensioners. And then they rob the flats they visited”.

I can literally see an existential crack creeping across the communal kitchen floor between us: despite the strong stigma attached to LGBT people, I can’t imagine what it is like to be born and raised in such a marginalised community, where breaking the law becomes the expected social norm.

Sometimes our daily life resembles a potlatch. “It is one thing to steal from the state, but it is a great sin to steal from the elderly”, says N. I am surprised to note that in the current crazy reality of ‘abolished’ law, this woman perhaps feels the disposition of the state and the people more vividly than those trying on state regalia in political exile.

N.’s family’s concepts of property, state, and law seem to lie somewhere between a childish worldview and everyday anarchism. Her understanding of humanism emerges from the smells of the kitchen, a glass of hot tea that she has after crying, and the nightly washing of the shared corridors — “I can’t stand it when it’s dirty”. Her life is about taking risks and gratuitous sharing of resources, whereas mine — the neighborly one — is about accepting other people’s experiences without moralizing and putting ethical contradictions aside. The second rule of the club is to share your food. The third rule is to never ask where it comes from.

During an interview at the Migration Department, an official reads out a human rights report on Belarus to emphasize that Belarus is a safe country for LGBTQ people, “just predominantly heteronormative”. The irony is that I am the author of that 2016 report. In that year, as an LGBT activist, it was very important to me that our country was not put on the back burner in terms of democratic change. If someone had told me in 2016 that six years later my organisation would cease to exist and my activist work would become invisible even to former colleagues, I would not have believed it.

Before the interview, a young activist from a local LGBT organisation trains us for possible questions about our sex life. They weren’t asked in the interview, and she was bored — she didn’t understand what all these regime supporters and political police had to do with our lesbian identity. I don’t get it either: my activist risk management never included the words “coup d’état”, but somehow that didn’t work as a protective amulet against the defeat of the human rights sector. It turned out that it was impossible to be “an activist but not a human rights defender” in the authoritarian power discourse. The interview goes on for ages, and when we leave the building it is dark and cold outside.

Moments from my childhood automatically appear in my head: I am five years old, Lukashenka is not yet president, and on a winter’s evening, my mother brings me home from kindergarten. The sky above my childish head is full of stars, the snow creaks under my feet. I shake the responsibility of this hard day off my shoulders. I am small and light.

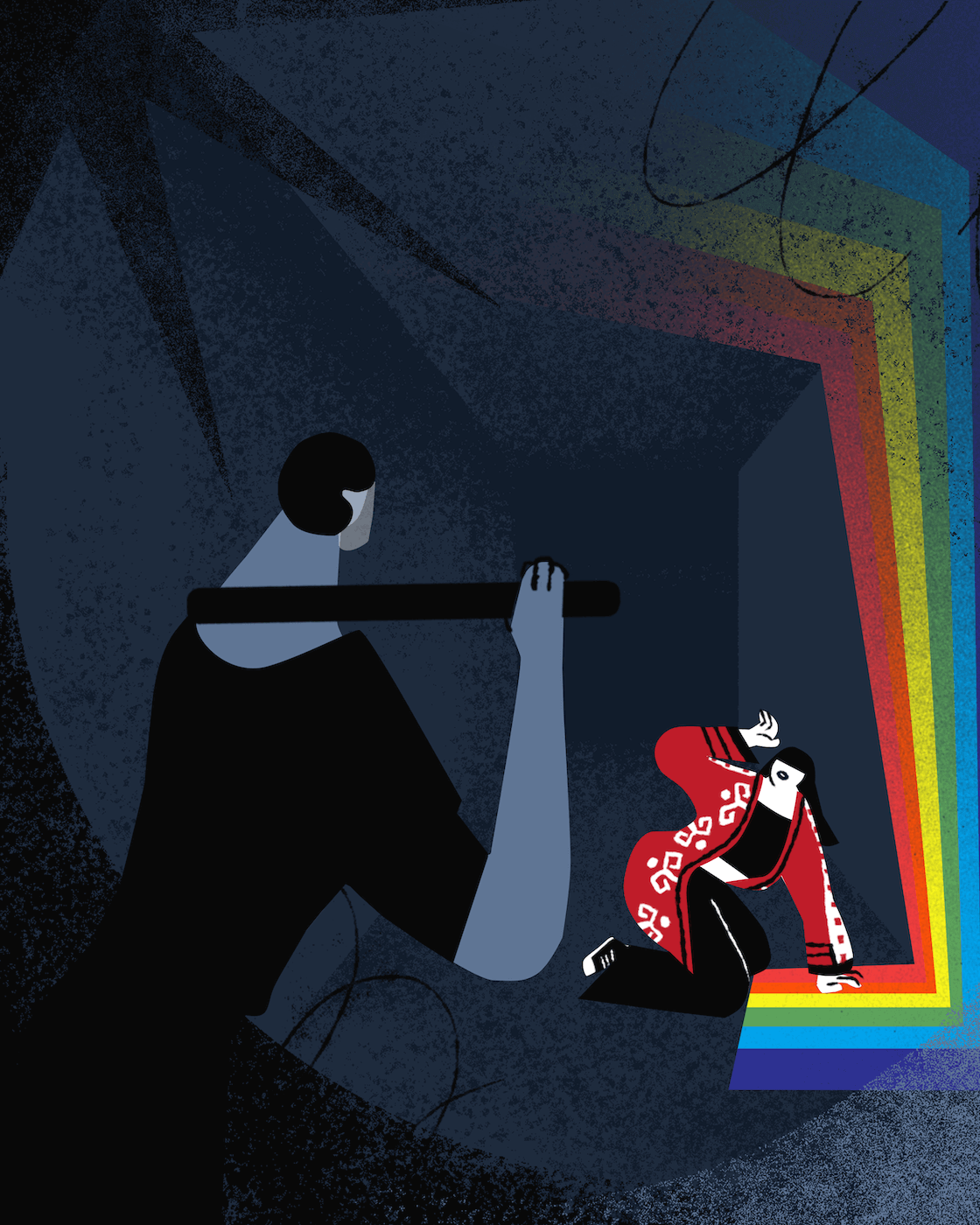

In August 2020 he “disappeared” on one of Minsk’s epic marches, and after serving his sentence he tried to challenge it. He and his family are refugees as a result. K.’s husband also seems to be a domestic abuser… My doubts dispel when K. starts crying in the laundry room and her husband threatens to punch her in the face in front of other people.

I see him systematically engaging in fights with half the dorm, complaining, yelling at other people’s kids, and being squeamish about communal areas because they’re too multicultural. Several times we have silly domestic conflicts: K. and her husband try to convince me that the amount of dirt someone leaves in the kitchen is related to skin colour. I ask them to stop spreading racist nonsense. As a result, she and K. stopped saying hello to us. For several months, my neighbors have lived in a state of ‘siege’. Contact with the ‘outside world’ is forbidden, the hatches are sealed.

Then I suddenly realize that K.’s husband’s behavior is not about “a squabbly character,” and not even about overt xenophobia — at least not only that. Psychopathic behaviour, increased agitation and aggressiveness, sleep disturbances, headaches, muscle tension, constant vigilance, hostility and distrust of others, inability to get close to people, avoidance of talking about traumatic events, blaming others, and exaggerating fears — these are all symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder that my compatriots develop in prison.

I’m the only one in the circle who needs an English interpreter, so I’m told in great detail about all the different types of hormonal spirals. I note that I’m a lesbian. The trainer laughs and changes the subject, asking the women in the circle which of them had undergone female circumcision in their home country. A young woman timidly raises her hand. The trainer continues by asking: “Does it hurt to urinate?” I realize that I’m just a sweet summer child with my previous ideas of what a lack of empathy might be like.

During the break, a local volunteer pursues N.: “You have too many children, you have to listen very carefully”. N. ostentatiously comes to the meeting wearing a headscarf and leaves when it comes to contraception. The juxtaposition of values might seem funny if they were on an equal footing, but they are not.

Here I see better than ever that, in the field of social work, it is very important to study the intersectional theory of discrimination. This is the only way to recognize the activist position not only as a helping one but also as a position of power. The problem is not even that we have no idea of our burnout without this reflection. The problem is that the public sphere of care in the age of capitalism is part of a dehumanizing machine.

The facilitator of the women’s circle asks us whether we feel safer here. M., my neighbor from Eritrea, explains that she feels much safer here than in Italy, where she and her child arrived by boat. She is asked to compare the level of safety with her country of origin. M. bursts into tears. There are no napkins in the training — this was a formal question with the expectation of a formal answer about equality. There was no room in the question for stories of child rape or street shootings. The stories hung in the air like splashing waves…

Translated by Valeria Khotsina

Illustrations by A.Mur

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect