“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

Kazakhstan is a constitutionally democratic republic. The honor, dignity, rights, and freedoms of all citizens are supposed to be protected by the state. But life remains difficult for Kazakhstan’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people. In effect, apart from legal restrictions, LGBTQ+ people in Kazakhstan also face violence and discrimination by law enforcement and other security agencies. Such cases are documented by activists and human rights defenders. However, it is difficult to protect the rights of those persecuted by officials, because it is usually the authorities who are supposed to safeguard the rights of citizens.

How authorities treat LGBTQ+ people in Kazakhstan

In 2022, Russia passed a law to completely ban “LGBT propaganda” among people of all ages. This continued the neighboring country’s restrictions on spreading information about alternative sexual orientation and gender identity. Officials in Kazakhstan have also proposed similar initiatives.

Majilisman Ardak Nazarov said in April this year that “LGBT ideology is aimed at dismantling centuries-old traditions and national values of the Kazakh people”. Following the example of the Russian Federation, the MP proposed banning information “propagating same-sex marriage and gender reassignment”.

In 2018, Kazakhstan already attempted to introduce a ban on “LGBT propaganda” through a decree of the Ministry of Information. Thanks to Kazakhstani activists and human rights defenders, the piece of legislation was not passed.

There are currently no specific laws protecting LGBTQ+ people in Kazakhstan. Authorities, such as the police or other security officials, often fail to prevent attacks on LGBTQ+ people and those who defend their rights.

For example, a conference on the rights of lesbian, bisexual, queer, and trans women was held in Shymkent in 2021 by the Kazakh feminist initiative Feminita. The event had to be moved to a neighboring café, where, according to Zhanar Sekerbaeva, a co-founder of the initiative, police and aggressive civilians were already present.

An unidentified group of men began insulting the activists, but it was Sekerbaeva who was eventually detained by the police. The aggressive crowd assisted the police and even hit the co-founder of Feminita.

Such instances of state officials refusing to protect citizens from attacks contribute to a sense of impunity among perpetrators of violence and hinder progress toward equal rights for citizens in Kazakhstan.

The Eurasian Coalition on Health, Rights, Gender and Sexual Diversity (ECOM) recorded 31 cases of violations of the rights of LGBT people in Kazakhstan in 2022, most of which involved extreme violence. According to the organization’s report, the most common cases are related to discrimination by law enforcement agencies: blackmailing and extortion through “sting operations”.

Human rights defenders claim that those harassed by Kazakh law enforcement are often afraid to complain against their victimizers. While documenting cases, activists try to maintain the anonymity of victims of such attacks.

Sabina’s story [name changed]

Last year a young transgender woman posted about her boyfriend proposing that they get engaged. She said yes – and posted a video of a Kazakh wedding ceremony. Insults and threats flooded the comments.

In the summer of 2022, the woman faced live bullying. She was out with a friend when unknown people attempted to drag him into a car. Sabina stood up for him, which resulted in the attackers filming her and hurling insults at her.

“The men who attacked us said that I had no right to wear national dress and to have a wedding ceremony. One of them swore at me and humiliated me in front of other people. As it later turned out, he had promised on social media to punish me and my boyfriend by all means,” Sabina said.

The woman called the police. Sabina gave her details and explained the situation to the duty officer. Ten minutes later, the police arrived. They listened to the conflict parties and took everyone to the district police station.

“We arrived there at 9 pm. They didn’t draw up any reports. We were just told to wait in the courtyard. But there was a group of people waiting for us there and they wanted to beat us up, so we went inside. I repeatedly told the police that I wanted to file a complaint, but they just ignored us”, the woman said.

A few hours later, when leaving the station, Sabina was again confronted by her attackers. They demanded the removal of the video of the wedding preparations from her social media. According to them, she had “dishonored Kazakh culture”.

“The police were also involved in the harassment. They were all part of the game. The policemen humiliated me, asking me personal and insulting questions, such as ‘What is under your dress’ or ‘Which one of us is the husband and which one of us is the wife’. They also demanded that I become a ‘man’ and stop disgracing Kazakhstan,” Sabina recollected.

Sabina and her friends were threatened with violence, and all of this took place in full view of the police. Fearing for her life and safety, she agreed to delete the video.

“The police officers continued to insult us openly and to our faces. They went on to demand that we apologize publicly on camera for allegedly disrespecting the traditions of Kazakhstan. They openly told me, in front of the police, that if I did not do it, they would slit my throat as soon as I walked through the gate. The police did not react in any way to these words,” the woman said.

One attacker used his social media to urge people to come to the police station to “punish Sabina”. According to the woman, the police officers took them out into an angry crowd of some fifty men. Almost all of them were filming Sabina while they were hurling insults and horrible and humiliating words at her.

“They called for murder, reprisals, and violence. I was forced to disclose my passport details, my year of birth, and my gender identity. All this under the humiliating shouts of the crowd. I had to fulfill these conditions because I feared for my life and the lives of my friends. It was clear from the behavior of the police that they were not going to protect us,” Sabina shared.

After this harassment, the young woman was taken to the police station to “provide explanations”. Sabina was denied the opportunity to press charges against her attackers. The woman and her friends were released at night when the crowd dispersed.

“I had to leave the city. I felt heavy and depressed. I kept getting phone calls, threats of violence, and death. The primal attacker demanded that I delete all my social media pages,” the young woman noted.

Sabina kept audio and video recordings to prove the harassment and screenshots of messages she received from the attacker. She contacted the TransDocha human rights initiative, which supports transgender people in Kazakhstan, and they helped her file a complaint with the head of the district police department, whose officers were involved in the woman’s harassment. After a while, Sabina decided to withdraw her complaint out of fear for her safety.

Mila’s story

Mila is a transgender woman and sex worker. In January this year, the police visited her. According to Mila, the officers pretended to be clients to enter her home and harass her.

“They threatened me with a fine of 1,035,000 tenges (around 2,075 euros) and implied that they would ‘find everything’ if they wanted to. One policeman snatched my phone and copied my landlady’s number. I was afraid I would be evicted,” the young woman said.

According to Mila, the policeman also deleted his phone calls so that she would not be able to identify his number. The policeman also seized the pepper spray she had kept for safety. It was never returned.

“The officers blocked the corridor and told me to get the money ready. I waited into the morning, hoping I wouldn’t be evicted. The police wouldn’t leave, making noise with radios, holding the door open, and shouting threats. I had to pay them $200,” Mila said.

The young woman admitted that the police visit her regularly. Sometimes, she says, she has to pay them off to make them leave quickly. Mila believes that the police are threatening her because of her sex work.

“Once, mysteriously, the police found 5 grams of white substance in my car. It had been planted. The results of the drug test I took showed the presence of cannabidiol in my blood. It is my understanding that it has nothing to do with the white and loose substance, but I have not been able to prove otherwise,” the woman admitted.

Mila points out that sex workers should not allow the police into their homes – and if they do, they should keep a close eye on what the officers are doing. TransDocha, an initiative that supports transgender women in sex work in Kazakhstan, published Mila’s story on Instagram.

“I decided to tell the story to save my sisters,” Mila said.

Alexander’s story [name changed]

Alexander runs an NGO supporting LGBT+ people in one of the regions of Kazakhstan. He believes that Kazakh security forces monitored his organization when participants gathered at the community center for events.

“The first thing we noticed was strange cars parked outside the office. When our community center had events, they were always there. The lights inside the cars were off. The windows were tinted and there was someone in the front seat wearing a cap. The cars would be parked next to the entrance to our office so they could see who was coming in,” Alexander says.

According to the organization’s director, the watchers were not interested in people passing by. Cars would come to the office almost daily. Alexander said the police once visited him to investigate a “verbal complaint”.

“This is a very clever move on the part of the police. If the complaint had been in writing, they would have had it in hand. I was told that someone suspects us of hosting Wahhabis. I let them inspect the premises. They then tried to ask me further questions. I asked the officers to leave,” Alexander adds.

Another case was less peaceful. One day, two policemen burst into the building where the organization’s office was located. Alexander was not present at the time. According to his co-workers, the police went through the floors and checked the premises.

“At the time, we were providing temporary accommodation for people from Russia who had fled the mobilization. Among them, there were both LGBT and heterosexual people. The police demanded identity documents from everyone present. They shouted “We are the authorities here, you shall follow our orders,” Alexander recollects.

After a while, the head of the organization started receiving messages on WhatsApp from the district police inspector. He demanded that Alexander give him details of everyone he had sheltered.

“I replied that they were registered through the e-Qonaq application. In terms of the law, all requirements were met. I asked the district inspector for a decision from the Ministry of the Interior or some other official document stating that we are obliged to provide information about those whom we have sheltered. I was told that I had an obligation to disclose their data even if they did not have such authorization documents,” Alexander said.

The young man decided to file a complaint with the officer’s superiors through the e-Otinish service. At first, the police did not take any action, except to send standard pro forma letters. After Alexander’s third complaint, a police chief came to see him and apologized.

“I contacted other human rights defenders to tell them the story. They were surprised that the police had admitted their mistake and apologized. After these incidents, we applied for a grant from an organization that provides security solutions for human rights defenders and activists. We got the money and installed cameras and a magnetic door. After that, the surveillance stopped,” Alexander concluded.

Ways to Ensure Protection for LGBTQ+ people in Kazakhstan

The Eurasian Coalition on Health, Rights, Gender, and Sexual Diversity (ECOM) recommends that the Kazakhstani authorities should:

- Adopt an anti-discrimination law that explicitly prohibits all forms of discrimination, including those based on sexual orientation and gender identity;

- Establish an effective mechanism to investigate and prosecute cases of discrimination;

- Amend the Criminal Code by adding a new paragraph to the list of aggravating circumstances: “Committing a hate crime based on sexual orientation and gender identity”;

- Amend the Criminal Code by adding sexual orientation and gender identity to the list of protected characteristics;

- Bring the process for legal gender transition in line with international standards, including removing the requirement for a mandatory thirty-day psychiatric hospital evaluation and mandatory surgery;

- Train police, prosecutors, and judges to effectively investigate and deal with allegations of homophobic and transphobic hate crimes.

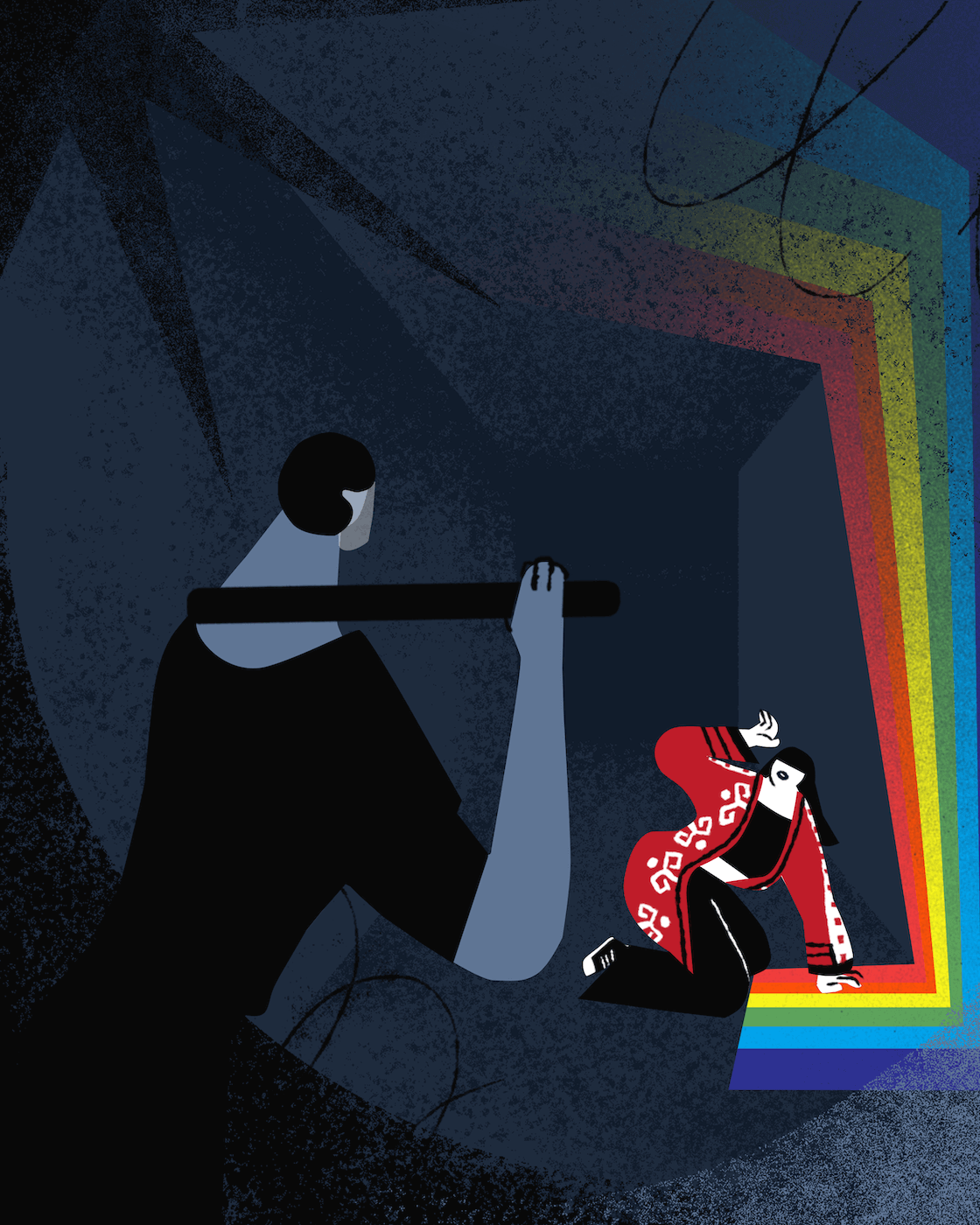

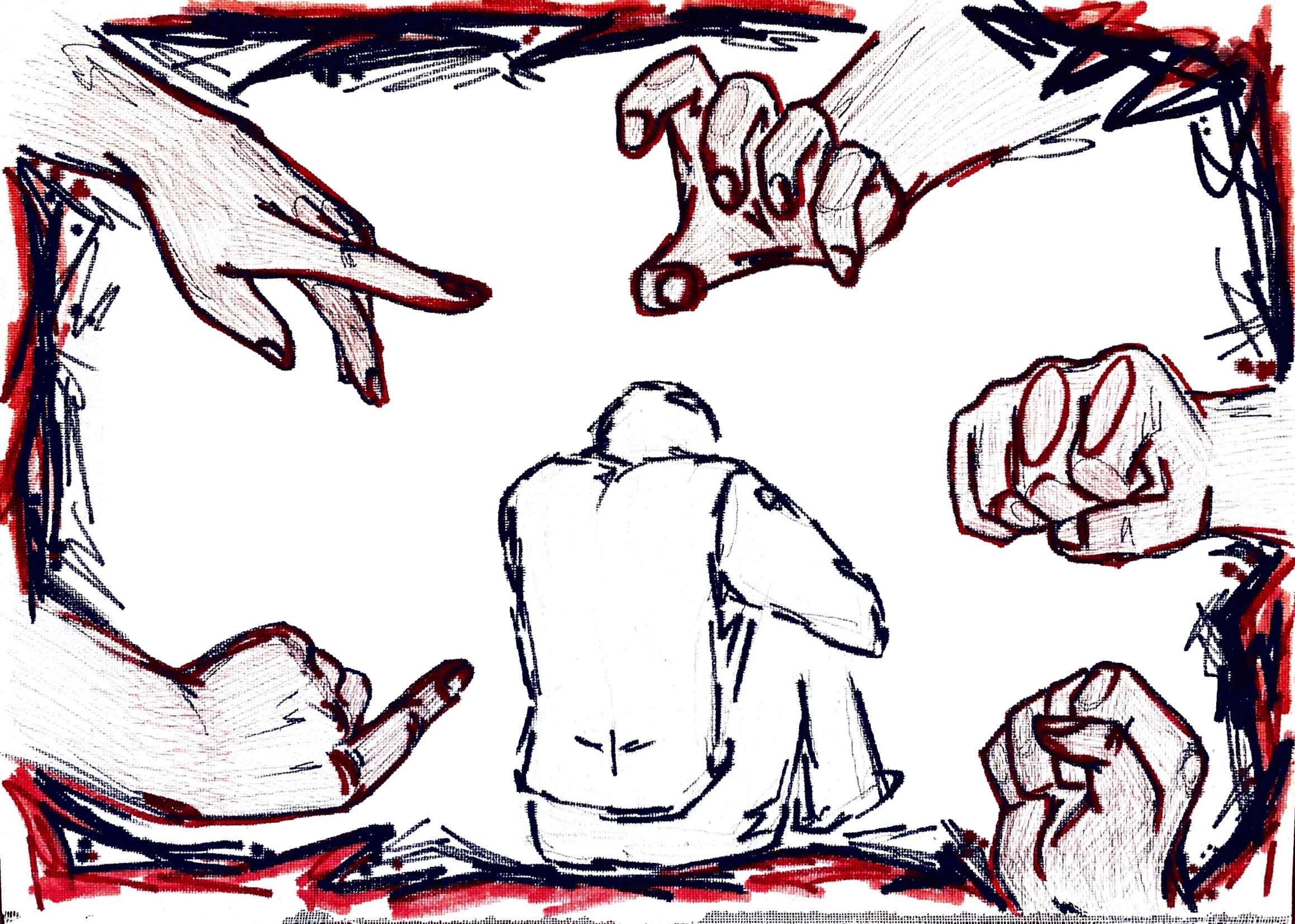

Translated by Valeria Khotsina, illustrations by carideaart

The original article was published here (in Russian)

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”