Three Stories from Moldova: Drag, Cinema, Literature

Shame Transforms When Stories Are Told in Safe Spaces

Writer Sasha Zare on why she uses a pseudonym, how long she worked on her debut book, and why representation matters.

The debut book of writer Sasha Zare, written under a pen name and released in 2022, was received with great enthusiasm both in the literary circles of Romania and Moldova and by the readers.

“Uprooting” tells a story about migration, femininity, and queerness and is the first novel of its kind published in Moldova and Romania.

The author made no compromises in addressing painful themes in all their complexity.

— Who is Sasha Zare and why does she write under a pseudonym?

— Using a pseudonym has been a big help in coming to terms with the potential exposure I would be getting. It became a sort of screen between me and the world. Post factum, with how much visibility the book has gained, it seems to have been a good decision. I would rather my book take center stage instead of my physical person. It seems to me that the text speaks for itself and says everything that needs to be said.

Also, I dislike the cult around authors and how much is expected of one person, and how much pressure is placed on one person when, in fact, writing anything literary comes from collectivity and interdependence. Even if you write alone at your desk, everything you write comes from the relationships you have with people.

You write for people. I wanted to be able to write about things that were potentially vulnerable or could make someone feel vulnerable, so I needed an inner negotiation where I felt protected by something. Sasha Zare, in a way, became a part of that protection.

— Your novel “Uprooting” (Dezrădăcinare), published last year, won an award in Romania and at one point became unavailable in the Republic of Moldova. How hard was it to get the book out into the world? Did you expect the reactions you got?

— I think I worked on the book for almost three years, with occasional breaks. Every few months, I would take a long period of time to focus on the book. I kept trying to find money so that I could afford a whole month off to make time for the book.

The book was like my guiding star. I was working to get money to focus on my book. That’s the sad reality particularly for debut books, but also for literature in general. Putting together a project this big requires a lot of struggle and at the same time, it’s something of a privilege.

There are no scholarships or support from the state, especially for debut works. In a strange sense, the pandemic helped me by taking away all social stimuli. I was living inside this contradiction. On the one hand, it was very worrying and depressing to watch the news and see everything that was happening, on the other hand, the pandemic period helped me. As for the visibility, I didn’t expect it. I thought the book would be confined to my small, literary bubbles, which I helped build over the years. Several friends, comrades and I started a feminist reading circle called “Dysnomia”, which lasted for several years. From time to time, I was also writing for them. It was a collective of several artists and researchers, we also published two zines. Many of us continued to write and encouraged each other moving forward. We had built these tiny spaces of ours and I assumed my book wouldn’t go anywhere beyond them. I never imagined it would blow up the way it did.

— Do you think it had to do with the fact that your book has covered a space that was missing? A space to explore the various topics that don’t often get talked about in Moldova?

— It’s one of the reasons, for sure. I think this step has to be made by some people who wanted to publish a new type of literature, non-existent up to that point in Moldova. A lot of people who wrote or wanted to write tried to fit into existing literary norms, myself included — I covered this extensively in the book — and it didn’t work. You take what you are given and you try to make the best of it. Or you can try to change that, at one point. So yes, I think not having this type of literature did make a difference. Nowadays it’s quite well-established and popular internationally, but it was nowhere to be found in Moldova’s published prose.

Alternative projects, feminist, queer, and contrarian ideas had made their way into poetry, but not so much into prose, which is also very much a patriarchal territory. And the most difficult territory to change.

Nowhere it is more difficult to be taken seriously for new ideas than in prose. Maybe it’s partly because writing a book of prose requires a lot more time and resources, which a lot of people, especially from marginalized communities, do not have.

There was an alternative to all the big publishers, called “frACTalia”, which had a clear political stance and a recent boom in publishing experimental literature. They published my book without mutilating it or forcing me to fit it into a certain box.

I kept writing throughout the years and have had texts published on websites, in zines, in magazines, and in newspapers. Still, I think it’s only when your book is in a bookstore, where people can pick it up, that your writing becomes legitimate. And we are free to feel whichever way about that. Personally, I can’t say I really like that. I would like people to publish everywhere, in any way, so that different types of literature become more accessible and widely read. My impression is that it’s happening a lot more now, which makes me happy. Romania has an increasingly active queer literary movement, with examples such as the X Literary Circle (Cenaclul X), which I am a part of, that publishes anthologies.

— How did you feel when your novel was ready to go out into the world?

— I felt the book was ready on more than one occasion. It was very interesting to see that my writing process was like falling in love: it consumed me entirely. I didn’t want to go to bed at night, because I wanted to keep writing or it seemed that sleeping instead of writing was a waste of time.

I never really knew how long until the book was complete, but I had a pretty good idea of where I wanted to end up. There was a lot of emotional work involved, a lot of harnessing the unconscious mind.

I also had moments of doubt, as I did with other texts, but not as much. Having worked on it so thoroughly for three years, I told myself it couldn’t all be bad. That would have been over the top. Still, I had my doubts and at first, I was reluctant to let anyone read it.

It wasn’t until I sent it to the publisher that I truly felt it was finally ready.

— To what extent is this book coming out and how much of it is autobiographical?

— I’m not really sure about the coming out part, given that I was already out as queer, at least in my circles. It wasn’t even my intention to do any queer/bisexual representation in the book, it just happened. My motivation to start writing stemmed more from the alienating feeling of being a migrant, like being stuck between two worlds.

I left Moldova when I was still a teenager and never fully came back. Writing came from a place of pain and longing, but also from not knowing what to do with it. These feelings are very specific to migrants, always between two places without really being a part of either. This was my starting point for the book.

From thereon, everything else came together organically. As for the autobiographical nature of the book, clearly, a lot of parts are autofiction, but many others are fictionalized. Things from which I extracted the emotional essence while changing the external setting. I had no intention of writing a memoir or my life story. What I wanted was to write prose, and the most convenient way to go about it was to work with material I was familiar with in a deeply personal way.

— “Uprooting” has a lot of talk about therapy. To what extent can writing and reading work as forms of healing?

— A few years back, I would have had a very clear answer to this question. I would have said that yes, writing does heal everything. Now I don’t believe in that anymore, partly because I’ve done many types of therapy and I don’t necessarily think that writing was therapy for me. Healing can be found in many places and can be triggered in many ways.

I would avoid any type of template for healing. By no means would I claim that writing about trauma heals it as if it were some sort of cure. Particularly because I know it can have the opposite effect and become retraumatizing. I went through this experience as a teenager, when I was writing about very personal and sensitive topics. Maybe I shouldn’t have exposed them to an audience, but I did it, out of the need for acceptance. And when I did it, it made me even more vulnerable. I don’t look back on that as a healing experience.

On the contrary, I found it to be retraumatizing, because it brought to light a wound that was not yet healed. Certain steps need to be taken in your story before you are able to not write from a place of hurt and then jump to exposing yourself to the public. In my experience, public exposure brings many things that don’t necessarily help, especially if you’re not writing about experiences you’ve already come to terms with.

What I think can be helpful is seeing your experience represented, and finding your life story again. Because all these feelings of loneliness, shame, and alienation make us antisocial and isolate us. Their origins are in trauma, but they are also a legitimate self-defense response to discrimination and oppression of any kind. If society has marginalized you in explicit and aggressive ways, it’s easy to interiorize that as part of your self-story. You may end up self-marginalizing in an attempt to protect yourself, making sure you don’t risk being exposed to the same violence.

— There is a part in the book where it says that when the world rejects you, it’s hard for you not to do the same. What role does culture play in this, including the alternative culture of Moldova and Romania, for people who feel rejected by the environment they grew up in?

— Unfortunately, I think it plays a huge role. And it’s not just about queer people, but about all people who face discrimination and social marginalization, such as Roma people or people with disabilities. If you don’t feel represented in culture, it’s like you don’t exist. This is based on the assumption that you have access to culture in order to consume it, but there are also people living in extreme poverty who must fight to survive. In such cases, representation is not enough. There has to be a whole social support mechanism in place to help these people, provided primarily by the state, but not only.

I think it’s a very alienating and strange experience to grow up not existing, not having a mirror in which to see yourself from the outside. You feel like you’re being told that you do not exist in this world, or that the specifics of your existence or the community you belong to are not worth being seen, appreciated, or celebrated. On the contrary, it is something to hide in shame. These are all messages you internalize when you don’t see your experiences reflected in the culture and in your community, or when you see them being presented in a completely distorted manner.

That’s the other thing: You can see your experiences represented in ways that are hateful, exoticized, devoid of any dignity. As a result, you feel belittled, invalidated, or reduced to a stereotype. If you never see yourself represented growing up, never learn about the stories of your community in school, and don’t see anything on TV about it unless it’s some news story disparaging your community, it will most likely affect your sense of self.

— If this book about uprooting, which is taking on a life of its own, was a sort of journey, where are you laying down your roots at the moment?

— The answer is I don’t know. I don’t think I’m laying down any roots right now, not definite ones at least. Living in another country and renting a place is quite a precarious situation, not the most favorable for laying down your roots. At the same time, my view on this matter is different from, say, my mother’s. The way I see it, you don’t need a house to grow roots, it’s more about relationships. And I don’t mean only romantic ones, although those are important to me, but a full social ecosystem. What I feel connects me to my life here, in Romania, are the people I love and care about. They are my most visible roots, but also the most fluid ones. Perhaps my roots can also be found in my work, my experience, and everything I’ve been doing for years and can now pass on through my writing workshops, which I love doing.

— How much do you think this book, perhaps even unintentionally, has done justice not only to the teens who found themselves in it but also to older queer people living in this space?

— I’ve gotten messages from people of different ages, from various social contexts. People took different things from different parts of the book. Some were only interested in the mother-daughter relationship explored in the story, others resonated more with other fragments. In a way, it’s an attempt to do justice to more queer identities and it was important to me to not tip-toe around the matter. I wanted to write from my own experiences and my community, rather than try to convince people around me of anything. This authenticity is something I value a lot. I also received messages like “The part about childhood was great, not so much after that” or “I really enjoyed the ‘clean’ prose, but less so the theories”. But for me, it was essential to combine the two and add a bit of self-theory, which is the theoretical approach to the affective experiences of being between worlds, identities, languages, and spaces. I wanted to challenge outdated literary norms, to erase this line between what is literature and what is not, what you are allowed to write about in a novel, and what not. How much of your view on life and the world you can put into a book, especially as a queer writer. How much you dare to express yourself as a woman and how many rules you break by doing so. I was very keen on doing all of this, gradually knocking down the walls that stood in my way and which, I’m sure, many others were faced with. Maybe that was my way of bringing some justice. I hope I managed to do it.

Cinema Can Change Attitudes and Cultivate Empathy

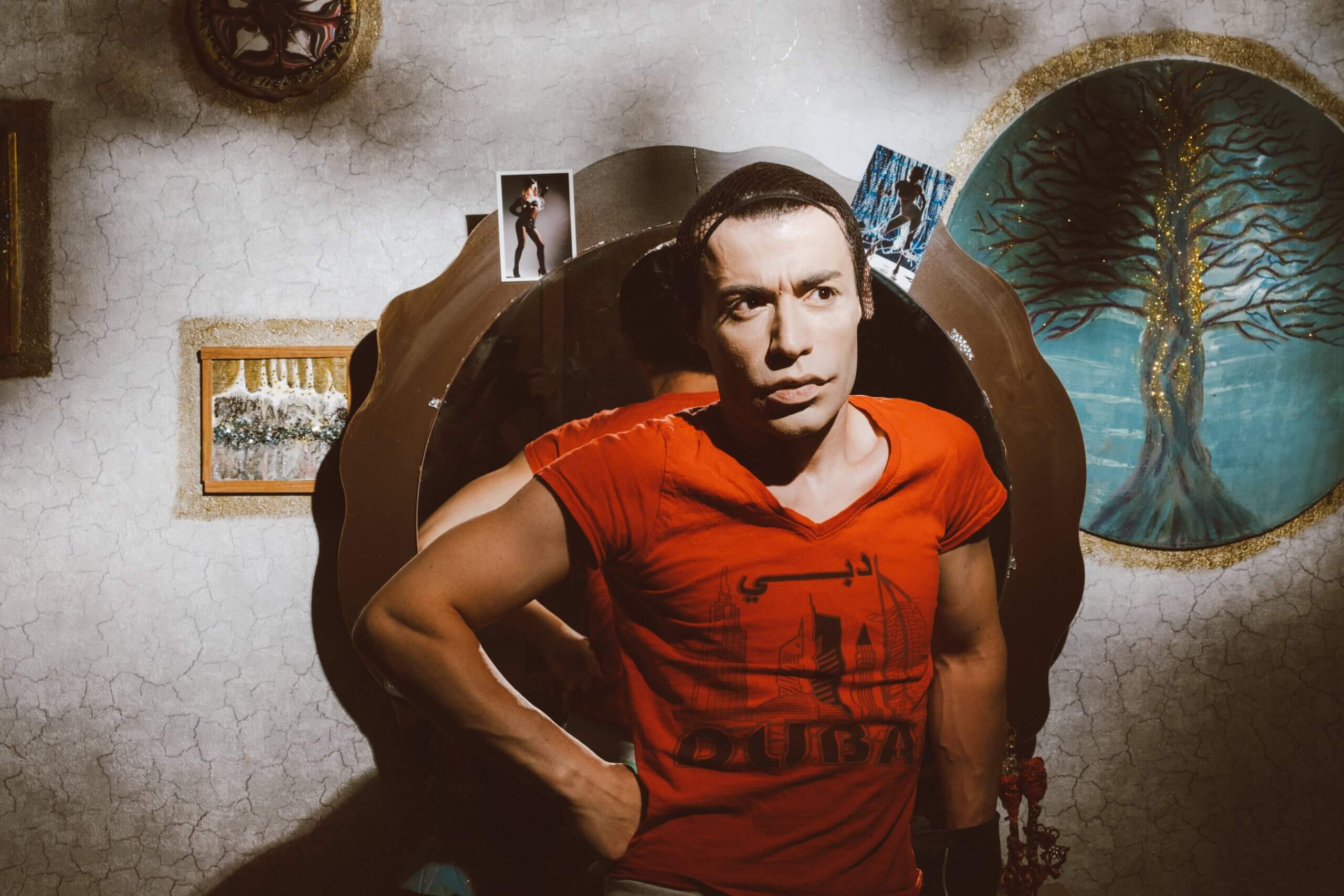

Interview with Max Cârlan, Director for Queer Voices, the first international film festival dedicated to LGBT+ topics.

In 2018, the first Queer Voices international film festival took place in the Republic of Moldova, the first event of its kind dedicated to the LGBT+ community. The idea came from the festival director, filmmaker, and screenwriter Max Cârlan, originally from the Republic of Moldova, currently living in Greece.

In this interview, Max delves into the story of how the path to Queer Voices was paved by Moldox, another international film festival with a focus on social issues.

In turn, Queer Voices then inspired the creation of Queer Cafe, an alternative culture space in Chișinau, where LGBT+ people can meet in a safe environment.

— What is queer culture in Moldova and what is it about?

— Queer culture in Moldova is not as new as we thought. A lot of people came to the first edition of Queer Voices, much more than we expected, the majority of which weren’t from the LGBT+ community that we knew. It’s hard to pinpoint the exact meaning of “queer” in Moldova because the queer culture in general is against defining itself in rigid terms. It’s not necessarily about sexual orientation, but more about taking a stand position and a way of seeing the world. It’s a way of life that is open, pacifist, inclusive, that is politically active, and can be critical. These are some of the attributes I associate with queer culture, including the one in Moldova.

— What were the first Queer Voices events like?

— Initially, we had a campaign to attract as many community members as possible. To our big surprise, only a few of our attendees were from the community. Instead, we had many people from the Chisinau community, the activist community, and from civil society. With each edition, I saw that new people are always coming to the festival, after hearing about us from friends or reading about the events in the media. We always see young people coming for the first time who are a bit shy. They come in, look, take a seat somewhere on the side, and watch the whole movie. They’re probably university students. What makes me happy is that we didn’t get any aggressive reactions so far.

— So there was never a case where you feared a possible violent incident?

— No, never. At times I may have been suspicious of organized groups I saw. Once or twice we saw some people gathering in the area. But we always have security guards who are very discreet. We just have to let them know there’s someone at the door trying to get in and we’re not sure of their intentions. Generally, though, there aren’t any issues.

— Why a film festival and why do you think representation is important in regions of Moldova that are far away from the capital?

— Well, I come from the cinema world and so do my colleagues, and we share this belief that film can change attitude because a film goes deep inside the heart of a character or a topic and thus cultivates more empathy. This was my position from the start: using film as an instrument to change people’s attitudes. I started putting it into practice with the Moldox Festival and I could tell from the discussions that followed the screenings that the audience enjoyed it. Besides, the films we feature are not likely to be on TV, so it’s something new for a lot of people. A lot of heart, thought and resources were invested in the creation of these films. That’s why we use film as a means of bringing people together with Queer Voices and Queer Cafe, which hosts a lot of cinema-related events. At Moldox, for instance, we show a film on this topic every year.

— Moldox also has an educational component — people can come and learn how to make a movie and explore their topics of interest. Why do you think it’s important for people — including queer people — to be able to grab a camera and tell their own story?

— There are a lot of subtle aspects when it comes to queer people’s perceptions or lifestyles. Such aspects are often portrayed as exotic by those outside of the community, who fail to do justice to the queer identity. Furthermore, queer or LGBT+ voices were put on mute for many years, so it’s important to have as many personal testimonies as possible, shared from the perspective of those who are living these experiences. It is an act of courage that also signals a sense of belonging.

— How did Queer Cafe come about and what has this alternative space changed for LGBT+ people in Moldova?

— Queer Café is the “child” of Queer Voices. We organized the festival in winter, when it’s cold outside, and we noticed that people came to the movies without spending too much time at the festival location, and then left. This was the case because there was nothing for people to do, nowhere for them to hang out and if there was a break during the movie, people just left and we weren’t sure they were coming back. We started thinking about a chill-out zone at the bar, seeing how a lot of people wanted to spend time there after the movies. People would stay and chat, it was awesome to see them spending time at the festival location. So we said, “Why not make a café here, that also works during the weekend?” And that’s just what we did. We got some funding that made it possible for us to open this space. We didn’t want a café or bar setting per se, but more of an alternative culture space, where people from different backgrounds meet. We wanted a place that promotes cohesion and inclusivity, where there’s always an opportunity to socialize, take part in a workshop, or go to parties where you’ll find movies, poetry, or art.

— How do you stay on top of things happening in Moldova while living in Greece?

— It’s something that’s on my mind a lot these days. The way I see it, it’s very easy to absorb negativity in Moldova. For sure the distance and living in Greece have enabled me to meet interesting people who are also amazing professionals, whom I could bring home for certain events. The best example is the amazing drag queen Chraja. Nowadays, with all the drag queens here in Greece, you have to be very lucky to get a hold of Chraja. I met her 5 years ago in the club where she is working. I would have never imagined Chraja would take me up on my invitation to come to Moldova – not once, but three times. She even managed to create a drag community here, which is no small feat. So I think that sometimes, being abroad can help you bring more value to those back home. This was the case with Queer Voices as well as Moldox.

— How do you see the queer cultural scene developing in the following years, considering that Moldova invests so little in culture as a whole?

— The queer cultural scene relies entirely on the support of international partners. If for some reason they will be out of the picture, that will be the end of queer culture in Moldova. I don’t believe queer culture would be a priority for Moldova, in the absence of external resources.

— According to various reports and surveys, in recent years, the Republic of Moldova has seen some improvements regarding the rights of LGBT+ people. From your own experience over the last 10 years, have you noticed any signs that we’re getting better as a society at understanding diversity?

— Yes, when we held the first Queer Voices edition or when we opened Queer Café. Just the fact that these projects can and do exist is a source of hope.

Free of Any Prejudice and Hate: Drag Shows in Moldova

At the end of last year, a team of drag performers was formed in Moldova who is now organising shows in Chișinău.

Jenny (22), an experienced dancer, is part of this team and shared the story of how the group emerged and developed, but also how they chose safe spaces for their events.

— How did dragqueens.md come to be and why is it important to have this collective in Moldova?

— It’s our way of expressing our queer essence. Both the group and the platform were actually the result of a workshop during the Queer Voices Film Festival, where we were guided by Chraja, our mentor and a popular drag queen from Greece. This interaction inspired us to create our own team that would do drag the whole year around and promote this culture.

— What was that like and how did you manage to get together and create this group? Moldova is not yet a very safe space to do that…

— It is, in fact, a bit hard to find people who are open. There are people who are interested but are afraid to take part in it, so they prefer just to watch from the side. We get support from friends and partners, who offer us spaces for us to put on our shows. They have to be safe spaces, because a drag show, in my opinion, should happen in a queer space.

— How hard was it to find these open platforms for shows on your own?

— Pretty hard, we had to search a lot until we finally found one. Not everyone is open to collaborations because not everyone understands queer art. And not everyone wants to learn about it. It’s a bit difficult to find locations for our shows, but we stay hopeful.

— How did you start doing drag and what prompted you to do it?

— I first found out about it online, from watching different TV shows that inspired me a lot, although I never thought it would be possible to do something like that in Moldova. My role model was Chraja — seeing her in Chișinău made me realize that I too can do that. I was a dancer before and was used to being on stage, so drag came as an extension of that. I grew out of being a dancer, but drag managed to tie in that experience with what I’m doing now.

— Having this dance experience probably made it easier for you to transition to drag…

— It was a sort of safe start for me but anyway, a drag performance can be anything. It doesn’t have to be a dancing and singing show, it can also be poetry, stage performance, or art performance. For me, dancing was a big help and a good start. It made me feel comfortable knowing I could entertain an audience and pique their interest.

— What were the first shows like? Were you struggling with the fear of going on stage? How did you overcome it?

— I took a long break after the last time I was on stage and yes, I was quite nervous, but once I got over it, everything went smoothly. I no longer had stage fright. Of course, I still get nervous before each show, like any person, because I put a lot of work into what I do and it’s important for me to see a good result. I really want everything to turn out well.

— What reactions did you get after the first shows where you went on stage? From my understanding, the audience was friendly, so I hope there were never any incidents…

— Actually, there were some, but I only found out about them later. We had a show at Queer Café and the team there intervened and saved us from that situation. A straight couple had seen a promo for our show online and came to see it. More visibility is always a good thing, of course, but we also have to exercise caution, because a lot of different kinds of people learn about us. Anyway, from what I was told later, that couple became quite aggressive in trying to get into our show. When they were asked to leave, they called the police to report that they were being denied entrance. In the end, they were kept out of the venue and the whole incident came to a resolution. I do want to thank those who took charge of the situation because we didn’t even know that was happening and thus, could focus strictly on our show. Other than that, we get some negative comments online, but we ignore those. Some can be a bit more sensitive to that kind of feedback, but I think that as queer people, we are used to facing a lot of hate both online and offline, so we have developed an internal shield to deal with all of that. We are very resilient.

— What does “doing drag” mean in Moldova? How can our country grow in that regard?

— I think drag is really unknown to Moldova, people here don’t really know what that is. To me, drag is a form of expressing myself, a way to bring a community together. I can’t say I’ve seen in Moldova any event that brings together LGBT+ people the way a drag show does. From my experience, each queer person has their own little group and rarely goes beyond it. When it’s a drag show, however, everyone gathers and socializes. It becomes clear in those moments that we are a large and powerful group.

— Which stereotypes and preconceived notions about drag shows have you encountered since being part of dragqueens.md?

— That women can’t do drag. I’ve noticed this prejudice even in our queer community in Chișinău. I’ve had some tense debates with LGBT+ people claiming that women shouldn’t do drag, because it wouldn’t be real drag. I don’t agree with that at all. The beginnings of drag are tied to sexism, during a time when women weren’t allowed to be in theater plays, so men performed the female parts as well as the male ones. That’s how drag came to be. Nowadays, the world is changing, everything is, and drag is more about expressing yourself than anything else. You can’t just take that away from somebody, claiming it’s not for him/her. We are very open-minded and don’t discriminate. We are free of any prejudice or hate.

— On the opposite end of the spectrum, what has been your best experience so far since doing drag shows?

— The most enjoyable experience is someone asking to take a photo with me after a show, that makes me feel good. My favourite show we did was the one at Pride Park this year because I saw a lot of new faces in the audience. I’m always glad to discover more and more people in our community because it means our community is growing and becoming more united day by day.

— Why is it important to have representation in Moldova, including drag representation?

— In my view, a drag show in the current climate can only be a good thing. We are living through some pretty hard times, with a lot of problems, but coming to a drag show allows you to just detach from everything and enjoy the art. It’s an opportunity to relax and socialize with new people. A drag show is an event that brings the community together and makes us feel good. We leave all our problems at the door and come there to have fun, communicate, and spend quality time together. A drag show is a very fun experience. I never met anyone who came to a drag show and thought it was boring.

— What does queer culture have in Moldova and what is it missing?

— It has many activists promoting love, peace, and other positive values. What it’s missing is queer spaces. There are some, but not nearly as many as there could be. It would be nice to work on improving this.

— What are your hopes and dreams for the future of dragqueens.md?

I’m hoping it will grow into a big independent project, with our personal space, more participants, more shows, and of course, always improving the quality. We have certainly made progress since our first events, but there is still room for growth.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Behind the Mask: Contemporary Drag Culture in Kazakhstan

Chemo Dao

Queer Self-Expression in Kyrgyzstan: Between Cultural Norms and Personal Values

Drag in Armenia: An Evolution of the Artform

Guess the Fact – Queer Artist Edition

“Discover Your Own Point of Tension and Pleasure. Trust Both”

Colourful Petals

Emotions. Feelings. Uzbekistan

Peculiarities of Running LGBTQ Spaces in Kazakhstan