Drag in Armenia: An Evolution of the Artform

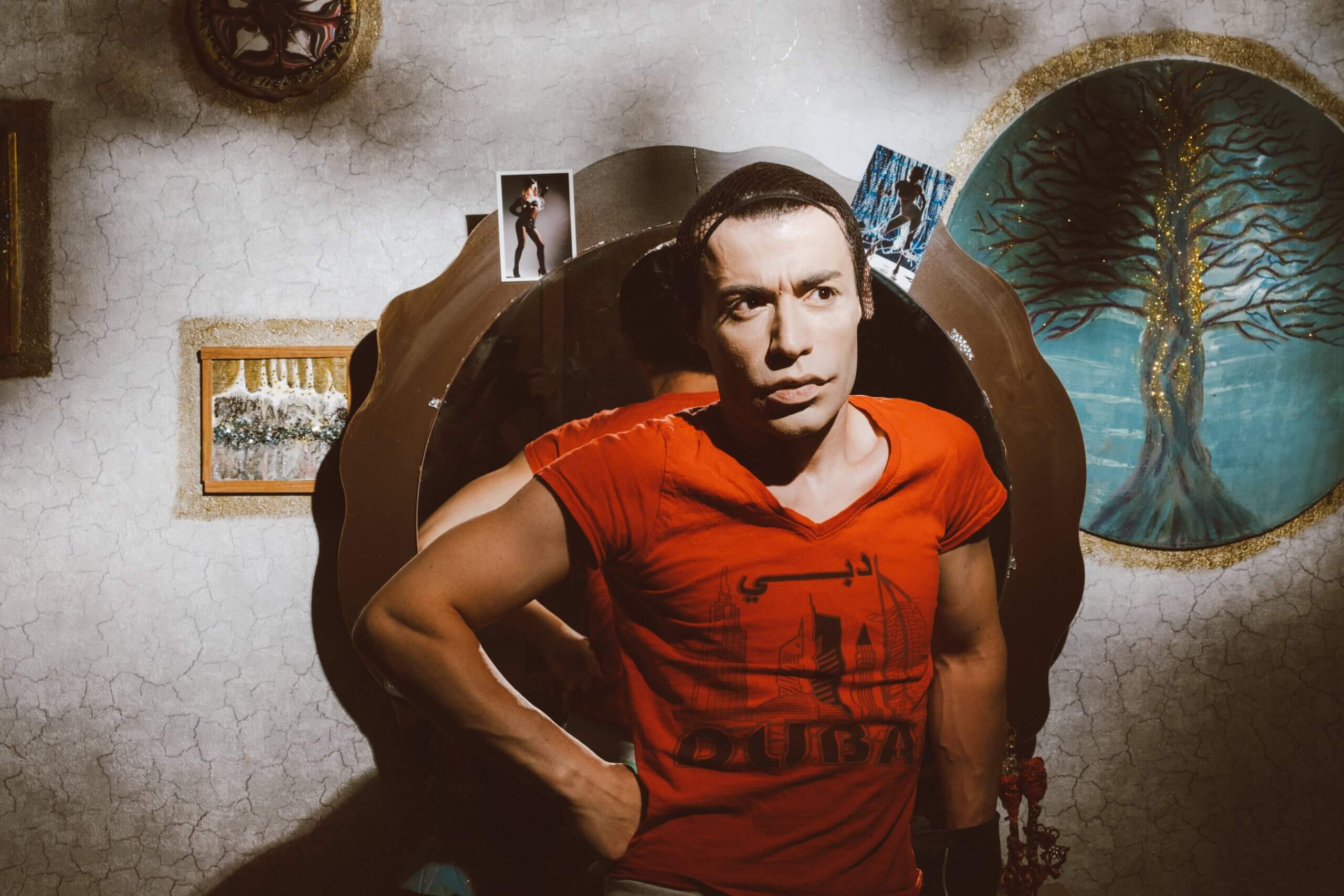

When Margo Patchi* started performing travesti in Armenia in 2016, drag and travesti shows were just beginning to gain popularity. Drag and travesti artists were largely limited to performing for free at spaces provided by LGBT+ non-governmental organizations or queer-friendly bars, she recalls.

Leona Love Vodkahouse started performing in drag shows in 2017. She recalls that she and her fellow performers were viewed as the “freaks” of the LGBT+ community at that time. Not a lot of people, even in the community, were familiar with either art form. Many confused drag artists with transgender women.

“It was fun back then because there was a lot of hate toward us. Now it’s boring. Everyone loves us. Hate motivated me more to do drag as a protest rather than a celebration,” Leona recalls.

“Doing drag is always expensive and we were doing it without a budget, using our own resources,” she continues. “All art forms need financial support to exist and grow, and without that, we were not able to create new looks or elevate our drag.”

Margo Patchi notes that there was one queer-friendly bar before the 2018 Velvet Revolution where most drag shows took place. It was closed down due to tax evasion not long after the new government came to power. However, this left performers dependent on the non-government organizations that supported them—and they did not always give drag queens total creative freedom. “There was always some kind of censorship which created obstacles for the art form to be free,” she said.

After 2018, major performers, like Leona and Margo, stopped putting on shows because it became too difficult to find safe places for them. Many even left the country.

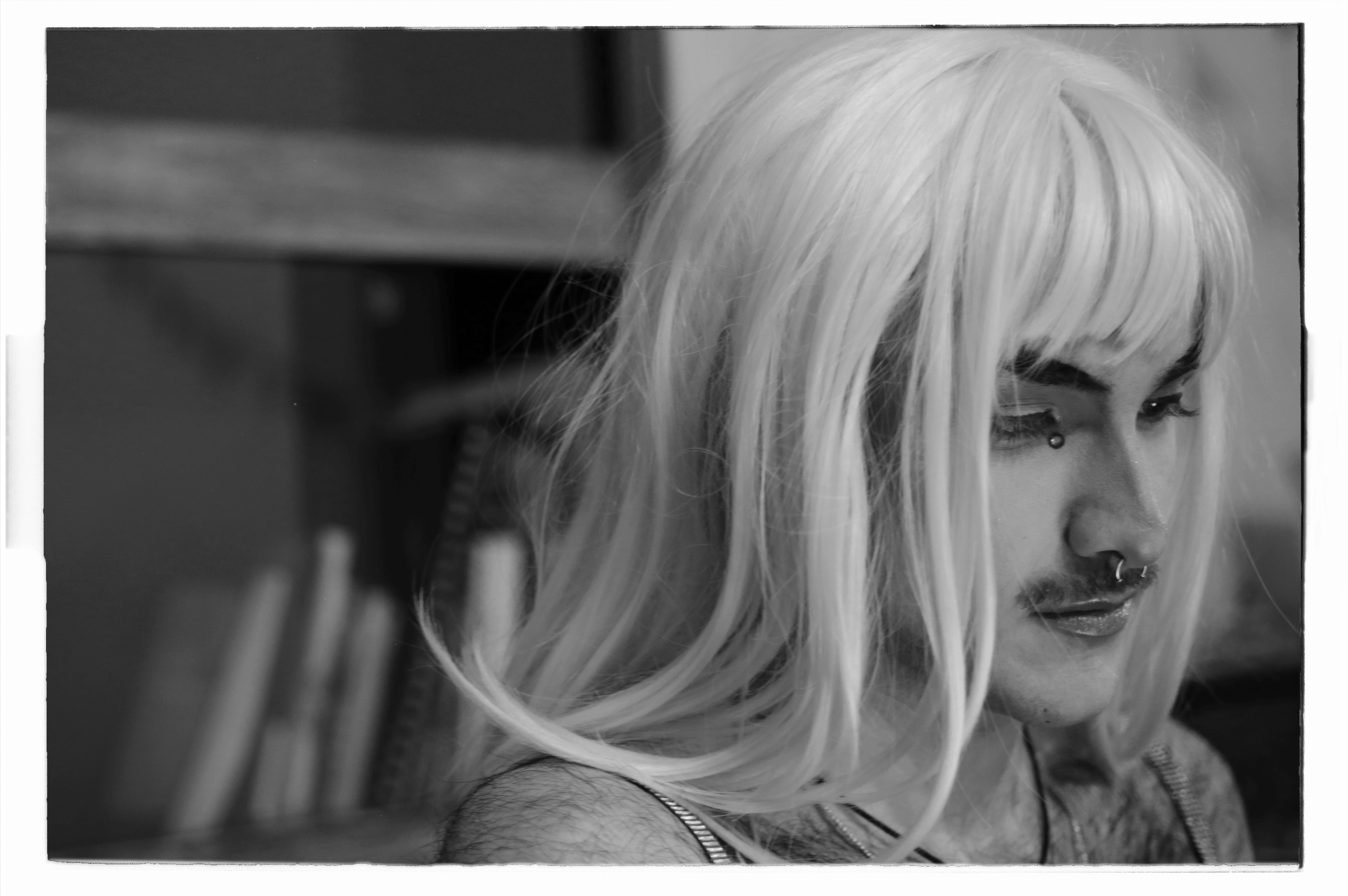

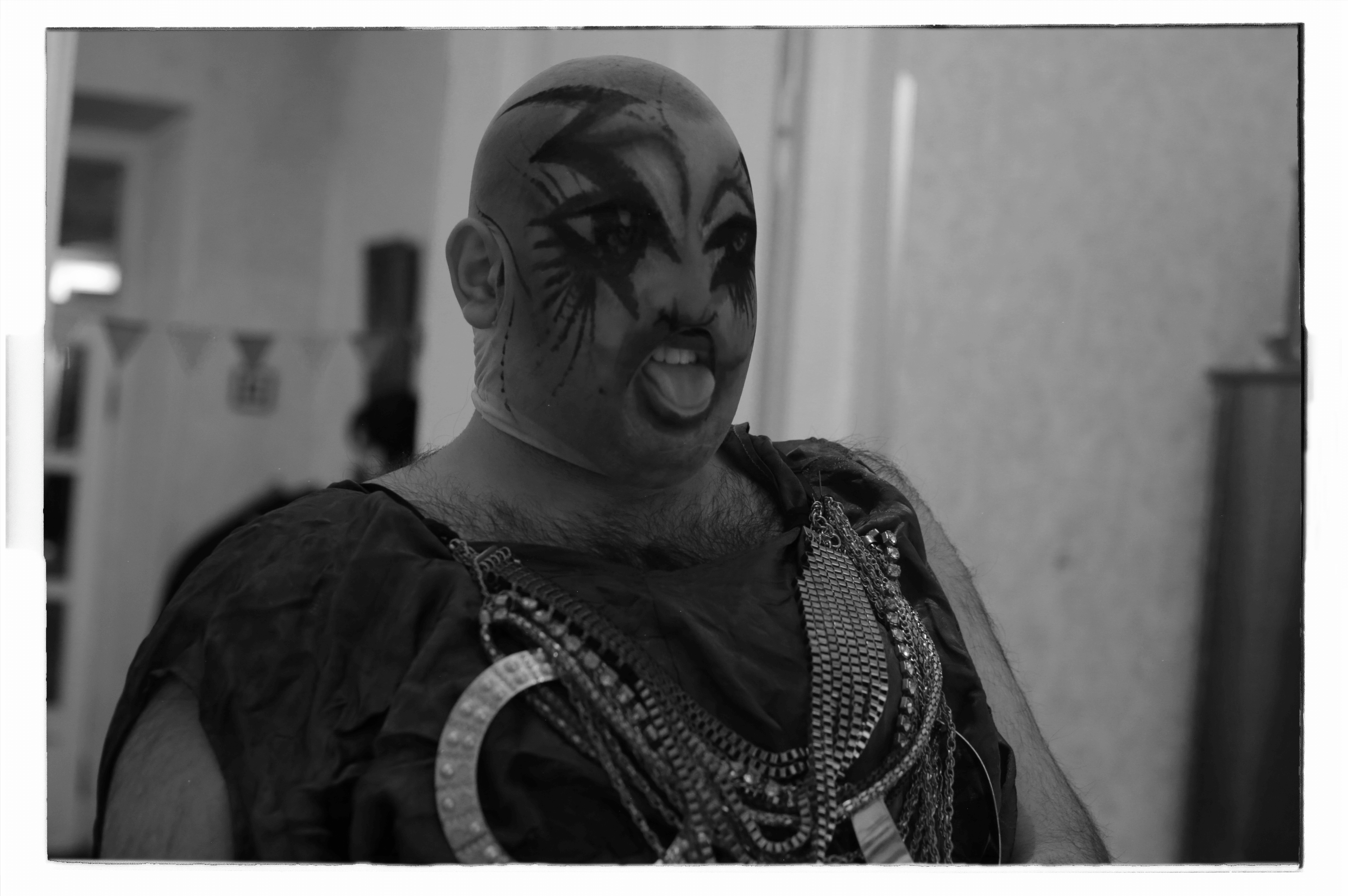

“Lady Die, February 2023”

Drag queen Sisi (a play on the Spanish word for “yes” and Russian slang for “breasts”) decided to use her last public performance to reveal her male persona, an attempt to show the audience how difficult it was to live the life of a drag queen.

“I knew I was moving to Ukraine and no longer wanted to do drag. I had accomplished my mission—I had motivated others, so I felt free to step aside,” she recalls.

Her inspiration was a song by the ethnic Armenian singer, Charles Aznavour, “What makes a man a man.” Throughout the years, many travesti divas have performed this number, during which they change into their casual clothes while the song talks about the difficulties of doing drag. By the end of her performance, much of the audience was in tears.

After a four-year break, new artists have started performing in Yerevan.

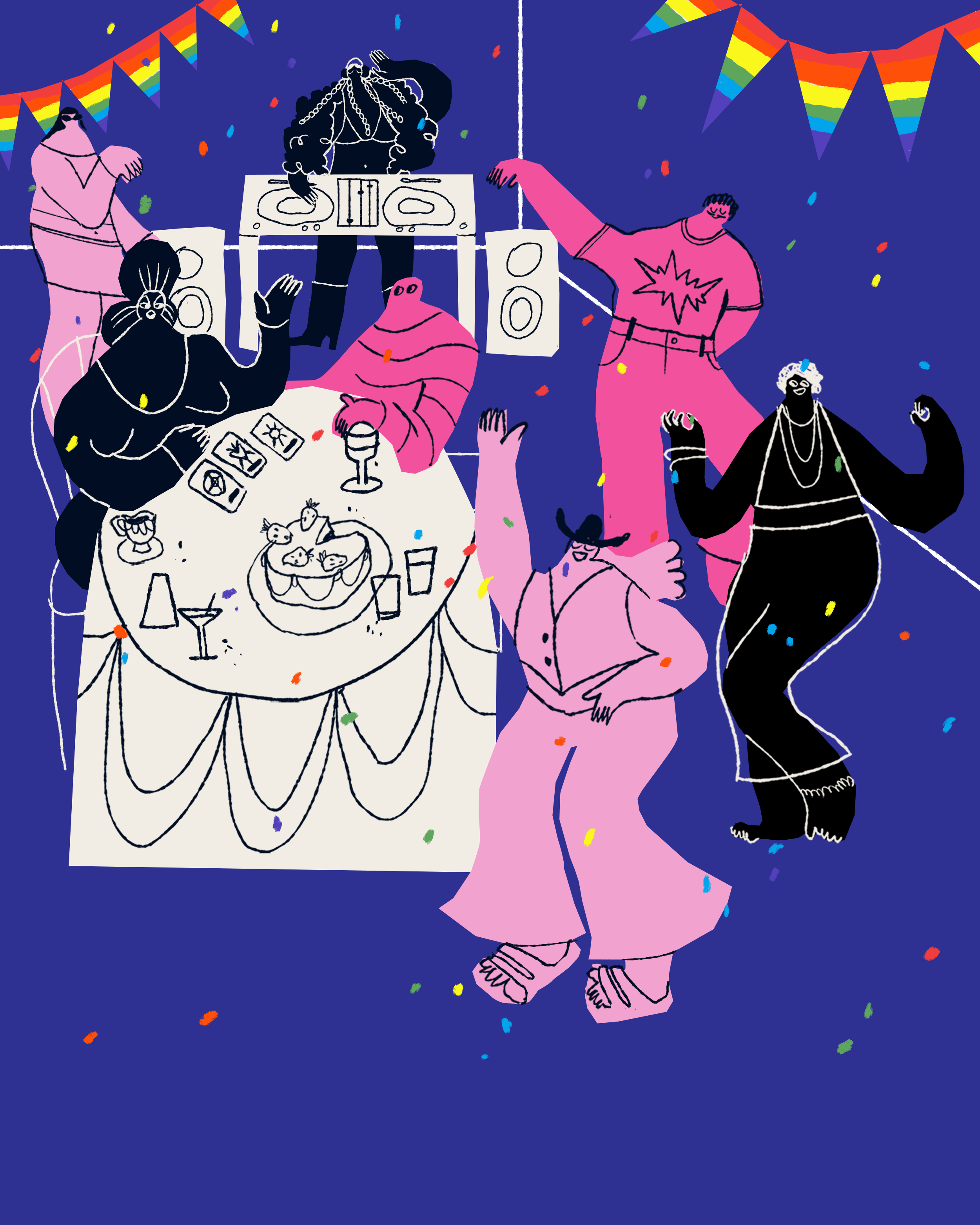

Four years later, new opportunities for drag artists began to appear. Old artists, such as Leona, started to perform again at new venues, like Poligraf, a techno club that hosts some queer events.

During a party to celebrate the anniversary of Pink Armenia in December 2022, five people performed, including new artists such as Frigid Bardo, Lady Die, Gigi Aries, and Remi Gelathoe.

The new artists are taking inspiration from Western drag performers while also looking for ways to express their own voices.

Remi Gelathoe first saw drag in person in 2021 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, where they lived for almost six years. After coming back and finding a queer community here, drag became a serious part of Remi’s life.

They decided to create a weekly drag event in Pink Armenia’s community center to give new artists a secure platform to discuss drag culture and watch films about drag history.

Lady Die, a cis woman in and out of drag, is working to challenge the norms in the queer community. She is inspired by her life and the concept of hyper-femininity, but sometimes she has to explain her drag to more experienced queens.

She notes that her everyday makeup could easily be an exaggerated drag makeup on the faces of the assigned male at birth artists, which shows the effort that she has to put into her art to fit in.

She adds that she faces slut-shaming because the freedom of femininity is associated with sex work, which is also highly stigmatized in the country.

Lady Die and Remi Gelathoe during a rehearsal in Yerevan.

Gigi Aries seeks to keep Armenian culture and society in her performance, although it is a challenge.

“Since childhood, we have been taught what Armenian art and culture is and how pure it is. Now, as a queer adult, who sees all the influences and layers that our culture has, it is very hard to find what speaks to my heart and which parts of national culture would be smartly used in my drag,” she says.

Gigi thinks that drag can be used not only to reclaim the presumably queer aspects of the Armenian history, such as Parajanov’s cinema but also to challenge aspects of a culture that have rejected the queer community, for instance by referencing popular Armenian comedy shows in their performances.

In Gigi’s view, right now globally drag is trying to be classified as art. She wants to perform in Armenia, even though safe spaces are still hard to find.

In the past, drag queens were freaks and existed only underground. Now I have the impression that drag artists all around the world are trying to say that they’re valid artists too, that they can both make money with what they do and create art, not ‘a freak show,’” Gigi says. “We’re all together in this journey in a way, even though we’re in different stages.”

A pair of Gigi Aries’ high heel shoes.

Right now there are individuals who are trying to keep the emerging art form alive in Armenia. Active artists believe that safe spaces and sufficient payment for performers are necessary to ensure that drag culture grows and develops in the country.

For instance, Sisi worries about safe spaces. She notes that if artists cannot find venues and aren’t paid, drag in Armenia will eventually fade away.

“We need to be smarter as a society,” she says. “First, it would be very beneficial for venues from a business point of view, because it would bring flows of people and money… For us artists, it’ll also be beneficial in another way, because it will provide a space for us.”

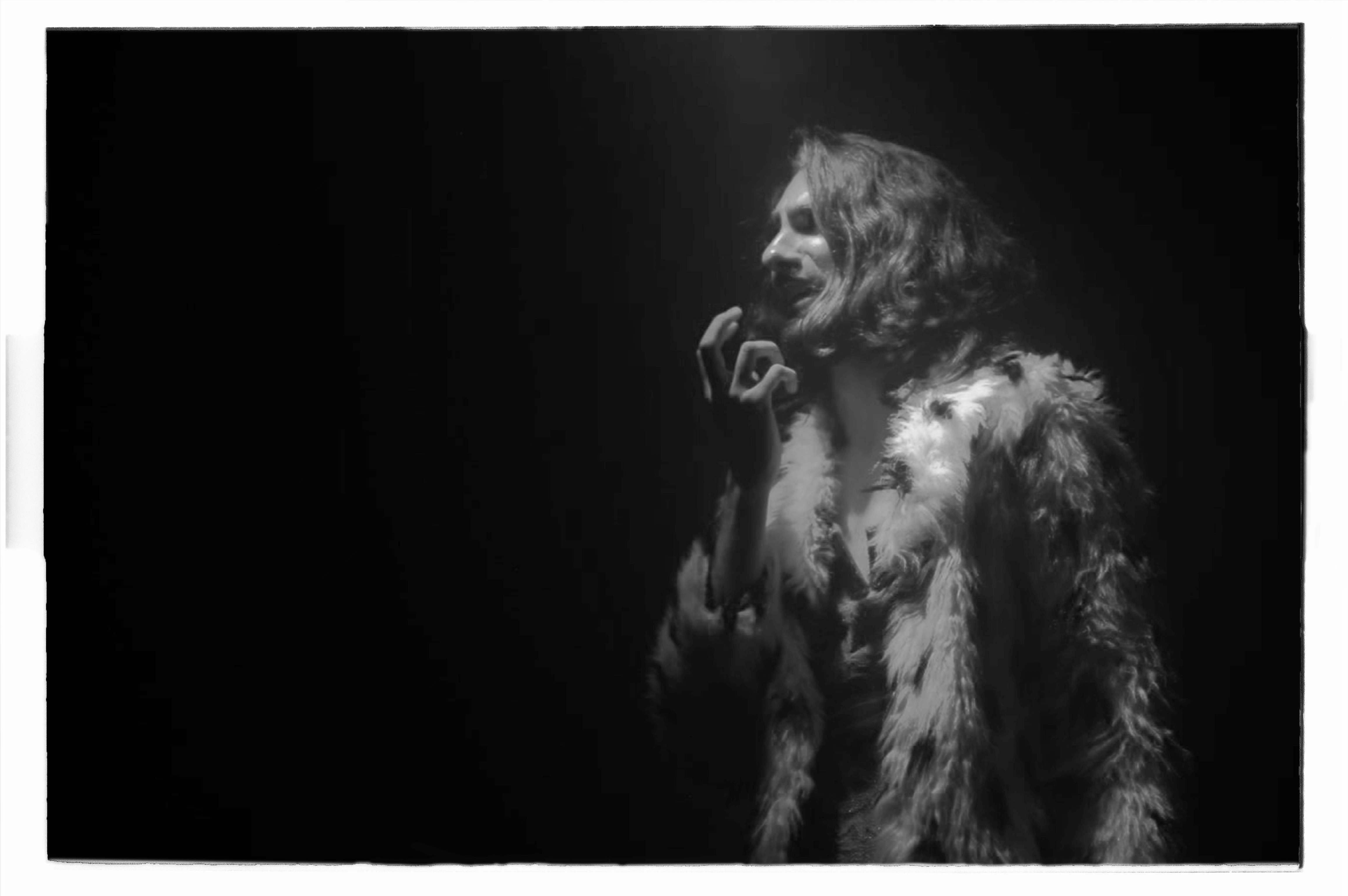

Gigi Aries performing at a club in Yerevan.

Gigi Aries, February 2023

A wig hangs on the wall in a drag queen’s apartment.

* All respondents are identified by their performance names for their safety.

Photographer: Maria Zakaryan

The article was originally published here (in English), as well as in Armenian

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Behind the Mask: Contemporary Drag Culture in Kazakhstan

Chemo Dao

Queer Self-Expression in Kyrgyzstan: Between Cultural Norms and Personal Values

Three Stories from Moldova: Drag, Cinema, Literature

Guess the Fact – Queer Artist Edition

“Discover Your Own Point of Tension and Pleasure. Trust Both”

Colourful Petals

Emotions. Feelings. Uzbekistan

Peculiarities of Running LGBTQ Spaces in Kazakhstan