In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect

For Maria*, a transgender woman and sex worker, even a simple trip to the store is fraught with risk. “When you go down to the store, you can be subjected to humiliation and harassment. Also on the street. There can be no question of transport, no trans person uses public transport. Everyone just uses taxis,” she says. “There is plenty of cruelty [in the world].”

[playht_player width=”100%” height=”90px” voice=”en-US-ElizabethNeural”]

While the LGBTQI community in Armenia is protected by human rights guarantees in the constitution, in reality, widespread homophobia and discrimination make it difficult for people to protect themselves.

Lilit Martirosyan, director of the Right Side NGO, notes that the local majority recognizes only two genders, male and female, and they have a set of rules in their heads about what a person should be and what they should do.

“And a person must necessarily be a man or a woman, necessarily cisgender and heterosexual. I am expected to start a family and have children,” she says. “People are not ready to admit the fact that there are rainbow people who do not fit into the system of binary perception of the world.”

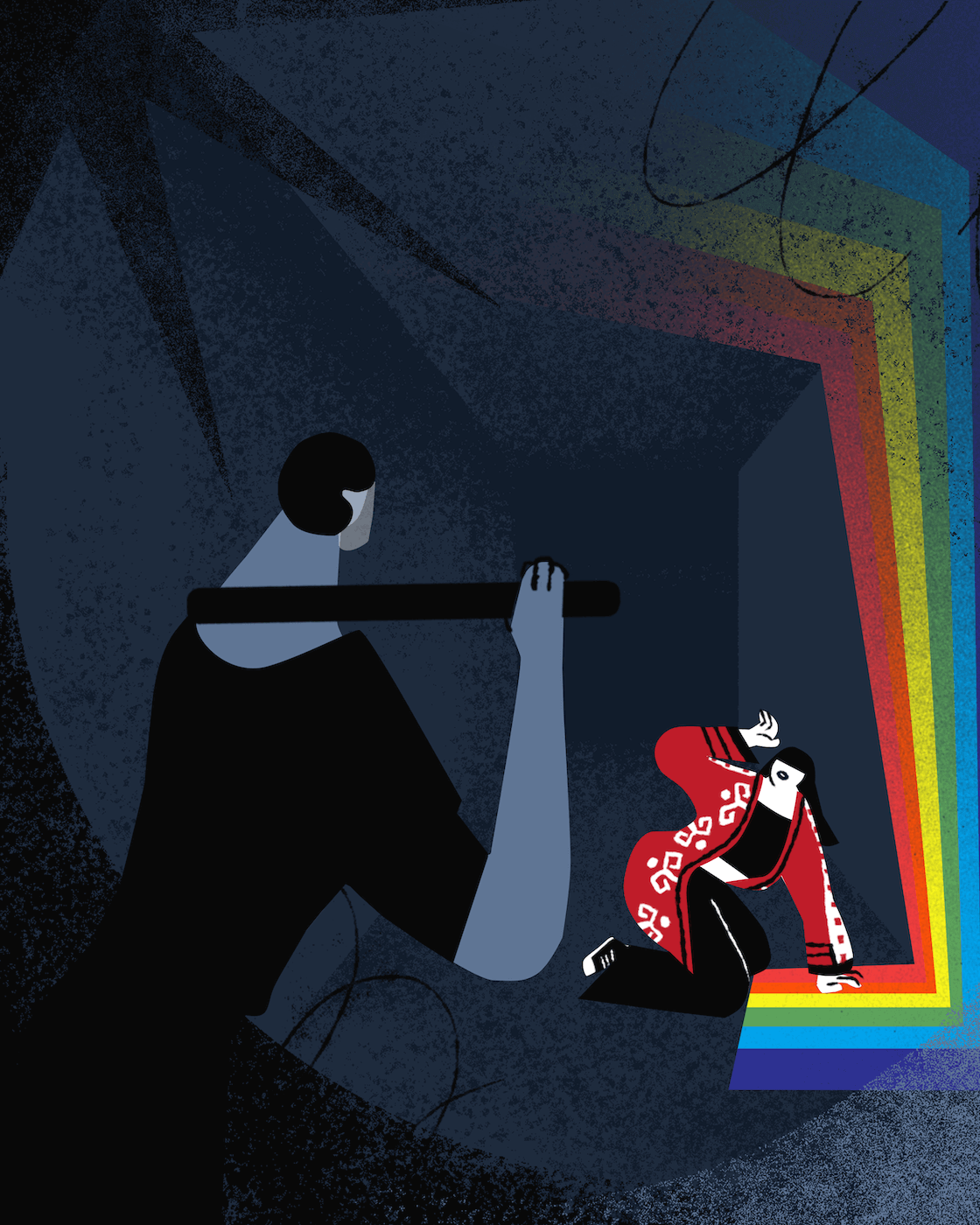

Lilit, a trans woman and activist, established Right Side to protect the rights of both trans people and sex workers in 2016. As the only trans woman to ever speak at the Armenian parliament, Lilit has experienced inequality and discrimination firsthand. In particular, access to health services is difficult and can be dangerous.

Lilit notes that the issue is even more acute because, starting in 2025, Armenian citizens will qualify for universal health insurance — except for transition-related services. Without insurance, hormone therapy will be prohibitively expensive for them. In addition, no doctors provide hormone therapy for trans people in Armenia today.

For Lilit, it is vital that trans people have access to all the services they need, from general examinations to the proper hormones.

“We are the first and leading organization in Armenia that deals with the issues of trans persons, we communicate directly with the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Justice,” she says. “In addition, we carry out various programs. For example, we had a program that provided more than 20 trans people with hormone therapy, general medical examination, meetings with an endocrinologist, etc. In addition, we are currently working with the government to start the supply of high-quality medicines and hormones to Armenia. Since many hormones needed by trans people are currently absent in Armenia. We also interact with foreign endocrinologists and psychologists. As well as people who can train local endocrinologists to help trans people.”

Many transgender people take hormonal medications for the rest of their lives, meaning they need to be regularly monitored by doctors. Plus, the transition process itself also requires close medical attention, both physically and psychologically.

“During a sex change, a person may have such psychological problems as depression, apathy, fears, phobias, anxiety, doubts, panic attacks, etc.,” clinical psychologist Vergine Ter-Gasparyan says.

“As a result of gender reassignment, people often face a discriminatory attitude from society, which leads to a constant state of stress. That is why, before deciding on a sex change, it is necessary to conduct a long-term psychological and psychiatric examination. A person should be able to get rid of the existing psychological problems that they had, work through all the traumatic experiences of the past, and realize that their decision was made in an adequate and healthy mental state. A sex change cannot be made based solely on your desire. It must be psychologically and biologically necessary, and in this case, a sex change can be carried out,” he adds.

Today, Armenian transgender people face discrimination both in hospitals and by psychological services and therapists. Henry, 21, an LGBTQ+ activist at Right Side NGO notes that the dangers are so high for some, they turn to friends to get the names and dosages of hormones they should take instead of seeing a doctor.

“There are only a few psychologists in Armenia who can really be considered psychologists since many still call homosexuality and transness a disease and mental deviation and try to ‘cure’ people from this,” he says.

In Armenia, though transness is no longer officially considered a disease, there is still no clear definition of these concepts at the legislative level.

When Karen*, a middle-aged transgender man and trans activist, began the process of his transition, it was still required to be officially diagnosed with transsexualism by a psychiatric state clinic. While this is no longer necessary, the process is still unnecessarily challenging: due to the lack of specialists, it is common for people to travel abroad or invite a doctor to Armenia.

It can even be difficult for the trans community to find doctors willing to treat them at all.

“There have been cases when people went to the hospital and doctors refused to serve them, just kicked them out,” he says. “While the situation is getting a little better, it still happens that there are people in the doctors’ waiting room who, if they realize that a person is trans, can start bothering them and forcing them to leave… there are a lot of such cases, especially in regions that are even more conservative, where everyone knows everyone. It is impossible to remain anonymous, and if someone finds out that you are a trans person, a nightmare will begin.”

As a result, trans people in Armenia often opt to try and avoid doctors, which can put them in danger, especially when they are taking hormones. Henry also notes that at times doctors refuse to treat them officially but take cash payments to provide “unofficial” diagnoses and prescriptions. Since the treatments are taking place unofficially, patients have no recourse against unscrupulous doctors or malpractice, he adds.

“It even seems to me that many trans people pray to God not to get sick, so that they don’t have to go to any health organizations and hospitals,” Maria says.

“The doctors are afraid to harm their reputation, but will do everything for money,” she says.

“What we need is a discrimination law and hate speech law. And a surgery law because we don’t have that practice. Right now, we don’t have a law about sex reassignment surgeries. It’s not legal or illegal… We don’t even speak about it. We need to work with the health ministry, justice ministry, and the National Assembly, if the other two won’t help.”

* Some respondents are identified by other names for their safety.

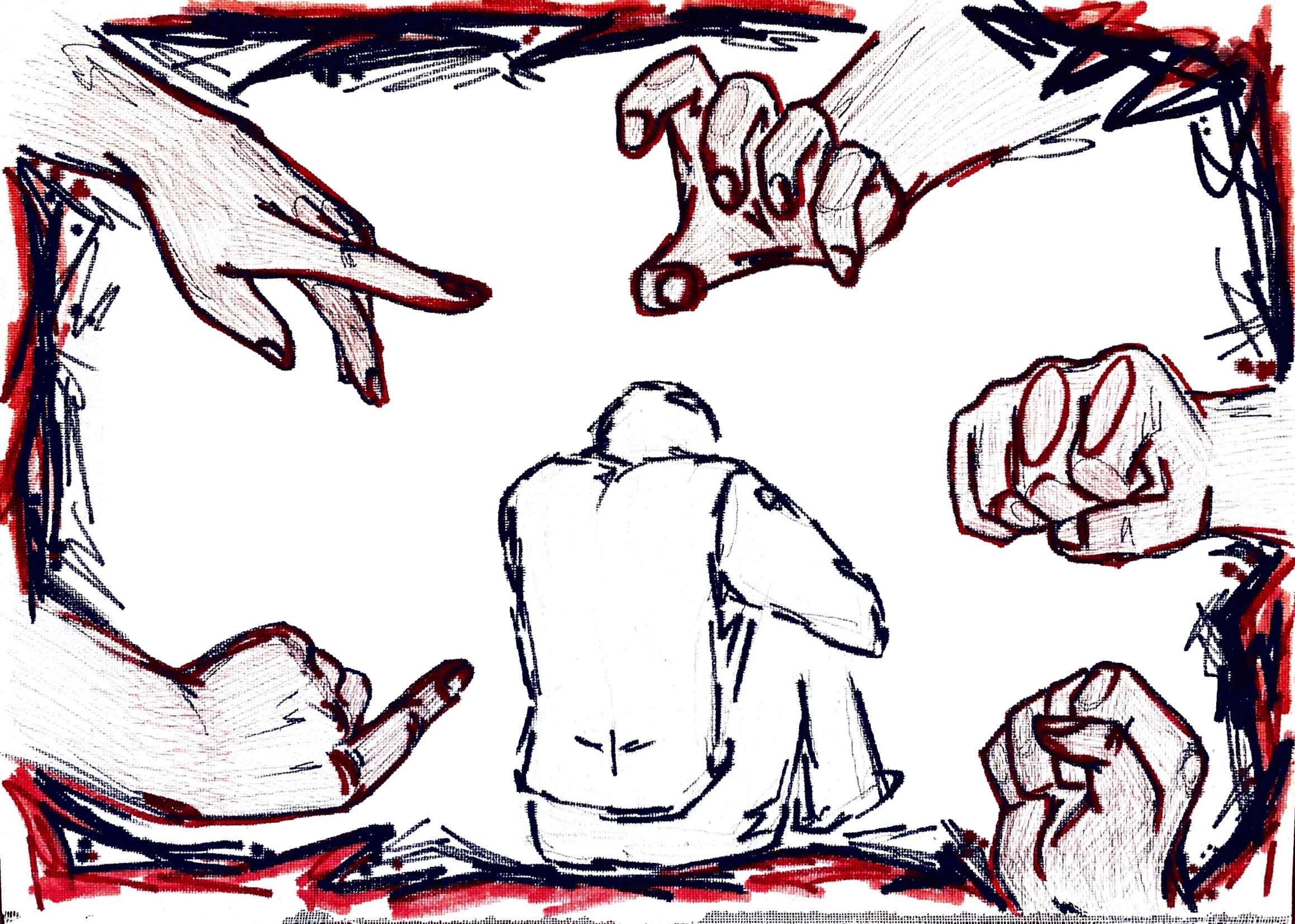

Illustrations by Mary Hovsepyan

The article was originally published here (in English), as well as in Armenian

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”