“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

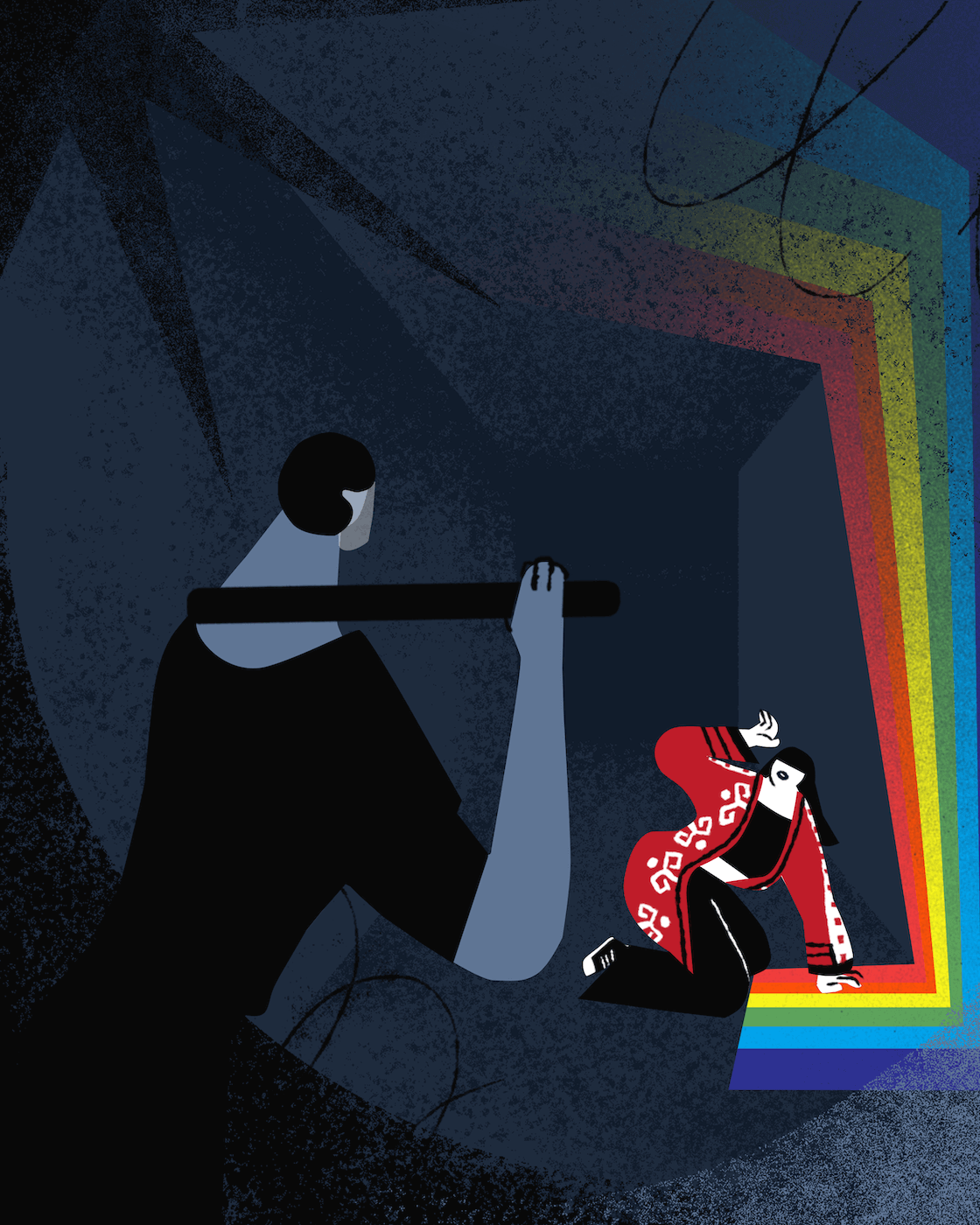

Despite progress in many areas and the gradual improvement of living conditions for LGBTQ+ people, Kazakhstan continues to be a relatively homophobic country in which queer people face discrimination, contempt, and cruelty.

[playht_player width=”100%” height=”90px” voice=”Noah”]

Our interlocutor, Askar, lives in Almaty and is openly gay. He told a difficult but inspiring story of how he served in the army and struggled with internalised homophobia, but eventually accepted his identity and began to live an honest and happy life.

Askar, 21

I am an openly gay man living in Almaty. I was born in Ekibastuz in the north of Kazakhstan. I work as a sales manager in a floristry business. I studied to be a programmer at a vocational school, but I didn’t work in my profession – I did it for the sake of a degree. I had a scholarship for the first three years of my studies and things were looking up.

On Coming out

I was 17 years old and applying for my fourth year at a vocational school.

On a summer night, I was going out with my friends. My mother was outraged: “Why? Who are all these guys? They’re all wearing make-up, they don’t look normal”. Those were my first queer friends. When you meet someone like you, it’s very valuable because they understand you. I was a rebellious teenager and I liked to stand up to my mother. She would ask, “Why do you have long hair? Why are your ears pierced?” That night, in a fit of rage, I shouted, “Because I’m gay”. I said I was leaving home. I moved in with a female friend, working and paying my part of utility bills and food.

I had a male friend at the time, also a queer person. He had tattoos all over his arms. My mother’s view was that he was a bad person and that he was on his way to prison. Before I left, she used to say, “He’s spoiling you. He’s a bad influence on you. Who is he? Is he your boyfriend?” She kept asking me if I was sleeping with him. Even though he was just a friend of mine.

After a month of living apart, my mother started writing long texts, calling me, and making me feel guilty. On the one hand, I felt sorry for her, but on the other, I realized that I wouldn’t be accepted in the family. My parents are very conservative. At the time, I thought I would never go back home. They seemed like enemies to me, I hated them.

How I got into the Army

One day I got a call from the military recruiting office. They said they were going to enlist me. I had to go to the military recruitment office with a draft registration slip saying that I was going to do my fourth year at my school. Looked like they backed off, but it didn’t last long.

I was at work when two men in uniform came in, asked for me, and tried to take me away. They said I had to go once again to the military recruitment office to confirm that I was a student, and then I could go back to work. I went, and in the car, they said, “That’s it. You are joining the military service”. I started arguing and pushing for my rights, which I wasn’t aware of at the time.

They said, “Your mother called us”. At that moment my brain just shut down. I could not comprehend how my own mother was able to make such a call behind my back. Later I called her, but she pretended not to understand. I asked her, “Why? Why would you do that?”

But in the end, I didn’t say anything. I passed the medical examination and was found to be able-bodied for military service. I resisted, but the draft board officers said, “We’ll send you to a shithole where you’ll be beaten up and you’ll come back crippled”. It was very frightening. But I manned up and decided to prove that I could serve, I turned high-minded.

Before going to the military unit, I called my mother again and told her that I needed some stuff. She came and burst into tears. I said, “Why are you crying? You sent me here yourself”. My mother came to visit me once in 2020 with my stepfather and my sister.

There were no problems related to my sexual orientation in the army. I wore a social mask for a year: facial expressions and affectation were erased in the army. I suppressed my emotions to survive so that no one would identify me as gay, so I wouldn’t get killed there. I know I wasn’t the only one who was gay, there were other guys. I even talked to one of them about it, but after two days he said he didn’t want any trouble and we stopped communicating.

Back from the Army and Dealing with Trauma

I was 19 when I returned to Astana from the army. The first night we sat down to dinner, my mother made Beshbarmak. She was very happy and said, “Askar, good job, you served your country, Balam. I am so proud of you. Soon you will bring home a fiancee, you must get married”. I replied, “Mum, nothing has changed. A year in the army didn’t and won’t fix me. It’s not a disease, it can’t be cured. I liked boys before the army and I like them now”.

I saw how upset my mother was and I thought I should not have said that. That’s where internalized homophobia comes into play. You have no hope of being accepted. You think you’re sick, even though you know you’re not.

I continued to live with my mum, and I got a job. I would go out with my friends, but I found it very difficult to express my feelings. They would make jokes and I physically couldn’t laugh. It was hard to cry too. My friend’s father died, I knew him very well. The friend was crying and I was sitting there stone-faced. I thought, “What’s wrong with me?” Now it’s over, but for about eight months after I left the army, it felt like I had no emotions at all.

The misunderstandings between me and my family continued. My mother used to say, “Let’s get you a job as a policeman, you’ve got a military record. We’ll figure something out”. I didn’t want to do that. I said, “Mum, I’m 19 years old. I’ve served in the army like you wanted me to. Here’s my diploma, here’s my military service card. What else do you want from me?” We fought all the time. I moved out again.

On Relationships with Girls

I had a thing for boys from childhood, but it was easier to communicate with girls: we could discuss which boys they liked. But I didn’t talk about my preferences, I just listened.

I started relationships with girls twice. The first one happened when I was in seventh grade. I was in love, but I wasn’t sexually attracted to her. When I was 16, I started seeing another girl. I liked her too, but I didn’t feel what I wanted to feel. It bothered me. I thought, “Here’s a beautiful girl, I’ll go out with her”. A lot of guys in our clique were jealous of me. In the end, I broke up with her. I said, “Sorry, I’m gay”. She was very upset, but we remained friends.

For a long time, I blamed myself for hurting that girl. After that, I was very depressed about my orientation and the relationship. I stayed at home and thought about what I’d done. I couldn’t imagine having sex with a girl. I fantasized about boys, but rather unconsciously, and when I realized it, I pushed those thoughts away and felt ashamed.

Now I realize that I was dating girls because I was trying to change who I was. At the time, I really wanted to change. But I couldn’t.

On Internalized Homophobia

In our family it was taboo to talk about sex, so there was no sex education. Once a guy in our clique told me he was gay. I started reading a lot about bisexuality, and homosexuality. I read and thought, “No, that’s not my thing at all”. When someone I knew said they liked another guy, I judged them.

All gay people have internalized homophobia. I would even say that the gay community is toxic, although that sounds very homophobic on my part. I think most LGBTQ+ people don’t accept themselves, so they have a lot of communication issues.

There are also a lot of straight people around me, which is a bit surprising. In Kazakhstan, if you are gay, you are usually friends with either queer people or girls. I am not only friends with girls but also guys, and boys from the hood. They only care about my personality. Above all, I am Askar, not gay Askar.

It was a year and a half ago that I fully accepted that homosexuality or any kind of queer identity is normal. Before that, I had been a raging transphobe for a while and couldn’t understand how you couldn’t be a man if you were born a man. It helped to realize that other people were thinking the same thing about me, “How can you be gay?” It helped me to see my own double standards.

On Gay Propaganda

Gay propaganda doesn’t work, and neither does heterosexual propaganda. I spent my whole childhood watching films with scenes of men kissing women and saw only heteronormative couples around me. But that didn’t make me heterosexual. I’ve never quite understood why public displays of affection aren’t propaganda for heterosexual couples but are for queer couples. The only thing that the lack of so-called gay propaganda had on me as a child was that I hated myself for too long.

On Relationships with Men

Very few people in Kazakhstan actually agree to give an interview or give their real names. Sometimes you meet someone on a website, you text for a week, and then it turns out that his name isn’t Aidar, but Kairat. People often ask me, “Is your name really Askar?”

Many fear what will happen if someone else finds out. If you are gay, you cannot be employed in many places, such as government offices. Although I had the chance to socialize, sleep or go on dates with officials, they asked me not to talk about it, to avoid mentioning their name to anyone. LGBTQ+ people who are closeted are very common, even in my experience: teachers, the military, and the police.

On Self-Acceptance

First of all, my people helped me: friends, the queer community, and my own sister, who did not turn away from me, even though the news came as a shock to her. Other straight people also supported me. For example, a classmate from Astana. He was not a queer person, just a guy from the south with a traditional Kazakh mentality. He was the first friend I confided in and told him I was gay.

He said, “Askar, no problem”. This is despite the fact that he comes from a religious family, just a backyard kid who lived “by the code of the streets”. It was very important for me to see that a person from such a background could accept me so easily.

About a year ago I moved to Almaty and started going to Amirovka [a queer safe space in Almaty – ed.] and I realised that nobody cares who you are or what your sexual orientation is. The local queer community is more enlightened than in other regions of Kazakhstan. Here I can go out on a date without worrying about how I look. Of course, it’s not all so perfect, but Almaty is relatively fine and safe.

In November 2022 I started to see a psychotherapist. At the end of our first month, I came out to him. Although he didn’t identify as LGBTQ-friendly, he acted professional and said, “It’s OK. Come back next month and we’ll talk about it”. The therapist helped me to work on accepting myself and on other aspects of my life. I didn’t know what to do with myself before. Now I feel much better.

Living in a Homophobic Society

I try to spend less time with homophobic and toxic people who express unrequested opinions, or people who ask inappropriate questions. It’s not like I ask guys on the street who they have sex with and in what positions. There have been times when I’ve been stared at in a shop because of my pierced ears. I used to check out and leave as quickly as possible, but now I ask myself, “Why do I have to leave? It’s not like I’m going to look in their bag to see what they’re buying”. The stupidest question I’ve ever heard is “Were you molested as a child?” Homosexuality is not a result of trauma.

Most of the time I avoid conflict, I’d rather walk away and keep quiet. For my own safety and peace of mind, I think this is the most sensible thing to do in most situations when living in a homophobic country.

On the Present and the Future

I would like to stay in Kazakhstan. It is very comfortable here, especially in Almaty. I don’t share the idea that we have to leave Kazakhstan for Europe. But if I encounter severe homophobia or persecution, I will have to move. It’s the worst thing to leave a country that you love but that doesn’t accept you. For me personally, it’s a nightmare.

I love walking in the mountains, it calms me down a lot. I love long journeys, I love trains and planes. In January, my friends and I are planning a trip to Vietnam, the first one for me. I want to travel and get to know other cultures, nature, and interesting places. Right now I am concentrating on myself and my peace of mind. I don’t have any global plans like getting married or having children.

Why I am Talking About It

I agreed to do this interview because I want my parents, the guys in my circle, and the whole of Kazakhstan, in general, to see that homosexuality is normal. Accepting oneself is a big step. I was really scared when I gave an interview to AIRAN: I was afraid of my family’s reaction, but I wanted to be seen. I’m not talking about popularity, I’m talking about visibility for the queer community, so that other people who have realized themselves as queer understand that this is normal. I’m just a normal guy who served in the military and grew up in a pretty homophobic family, but I keep going and I’m not afraid.

It is normal to be gay or lesbian. Being a transgender person is also normal. To be afraid, to hide, is terrible. By living in fear, turning a blind eye, and deceiving yourself – you only ruin your happiness and live a completely alien life. I wouldn’t want that. I have given up a lot to be who I am.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

Influence

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”