From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

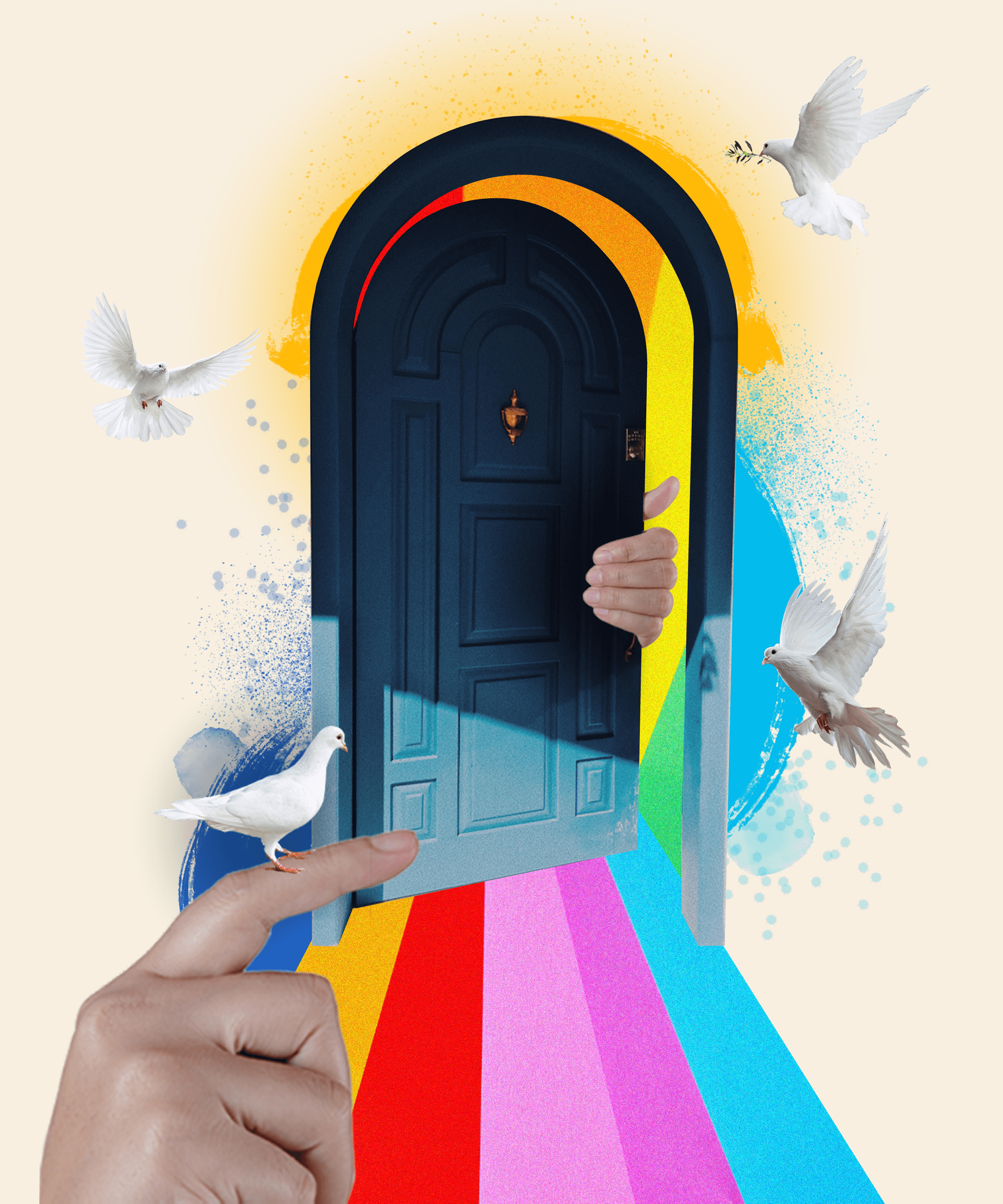

After years of trailblazing activism for the Georgian queer community, Nata Talikishvili is now using humor and storytelling to bring the everyday challenges of queer people to a wider audience in Georgia.

[playht_player width=”100%” height=”90px” voice=”en-US-ElizabethNeural”]

In the intimate space of the Klara Bar in the capital Tbilisi, Nata brings the audience in — inviting them to experience the difficult and dangerous life of the LGBTQIA+ community in Georgia today.

“At first, I was terrified,” Nata recalls. “I didn’t think I could do it, but the audience adored me, and it made the process much easier.”

Stand up is a new profession for Nata, a trans woman who has also been a chef and activist. Her show, Call Me Nata, was born when the owner of Tbilisi’s well known Club Basiani, Naja Orashvili, and a queer activist, Giorgi Kikonishvili, overheard Nata speaking with people at the club. When Klara Bar opened in 2022, Nata’s show opened with it.

“As they told me, the reaction of the crowd, the focus on me, the sound of applause and laughter were indicators that we could start something new,” Nata recalls. “Klara Bar was created around this concept, as a space that would be more focused on socializing rather than entertainment or music.”

Photos by Tako Robakidze

For Nata, the show has offered a new way to be an activist and push for a better life for Georgia’s queer community. Georgia, where homophobia remains widespread, has been slow to protect the LGBTQIA+ community from discrimination and hate crimes. While Nata was raised by two grandparents who accepted her as she was, few others accepted her in her native village of Norio, in eastern Georgia. After her grandparents passed, a relative sold their house and left her homeless. She was just 15.

“I was sure of my gender identity from such a young age that I had no idea what the fear was, so I didn’t have any problem sharing with others that I was a girl. My grandma and grandpa supported me from the start and tried to provide me with the information I needed. Their attitude helped me to accept myself,” she says.

“Everything changed after their death. Soon I realized that people I thought loved me were only thinking about themselves — some of them even stole things from the house where I grew up.”

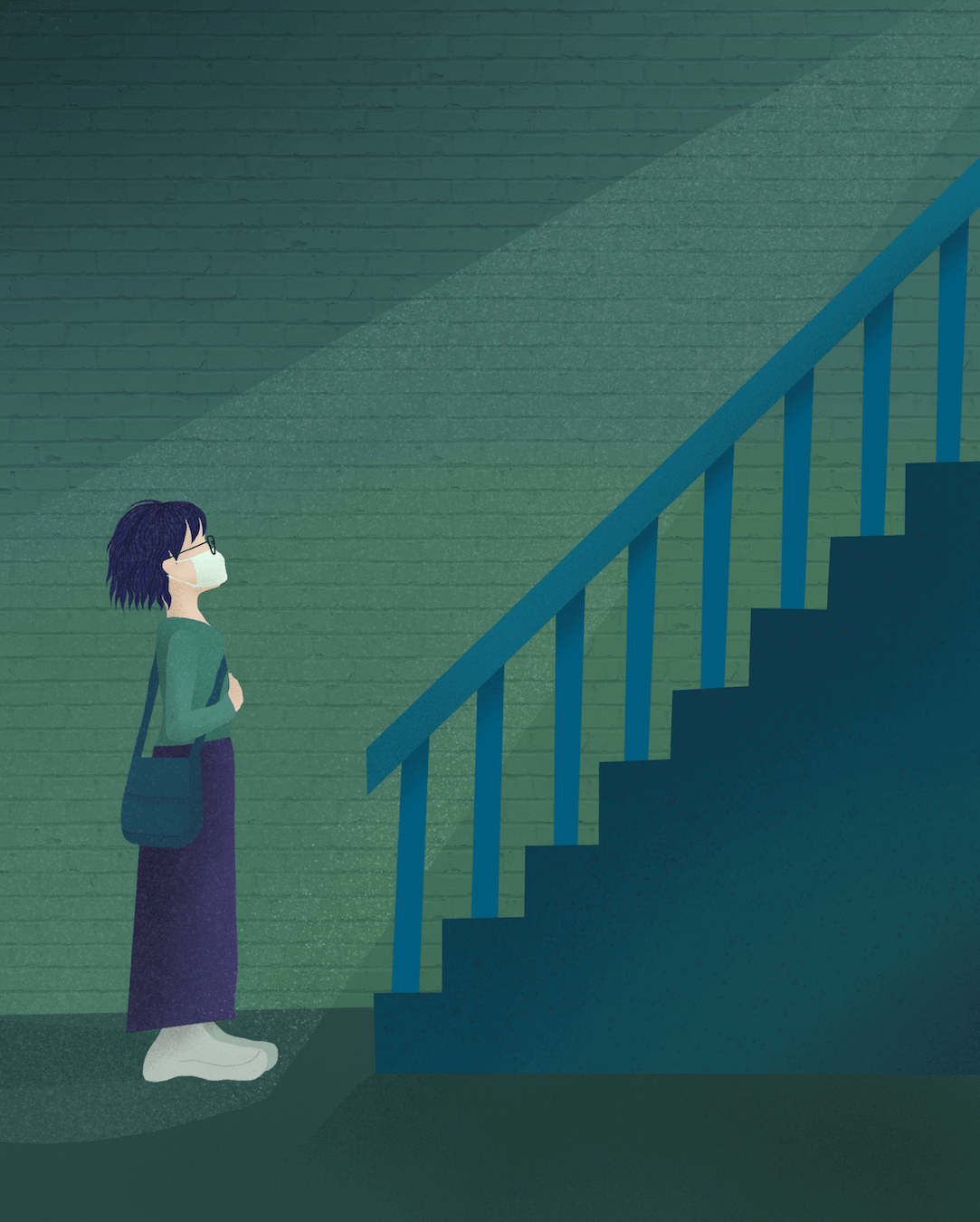

She decided to move to Tbilisi. It was 2006, and at the time, the queer community in Georgia faced daily harassment as well as physical assault. Police often treated them violently, and no one was held accountable. When she first arrived in the city, Nata lived on the streets for a few days before moving in with two older trans women.

Life was difficult. Nata supported herself through sex work and learned she had to depend on herself for her survival.

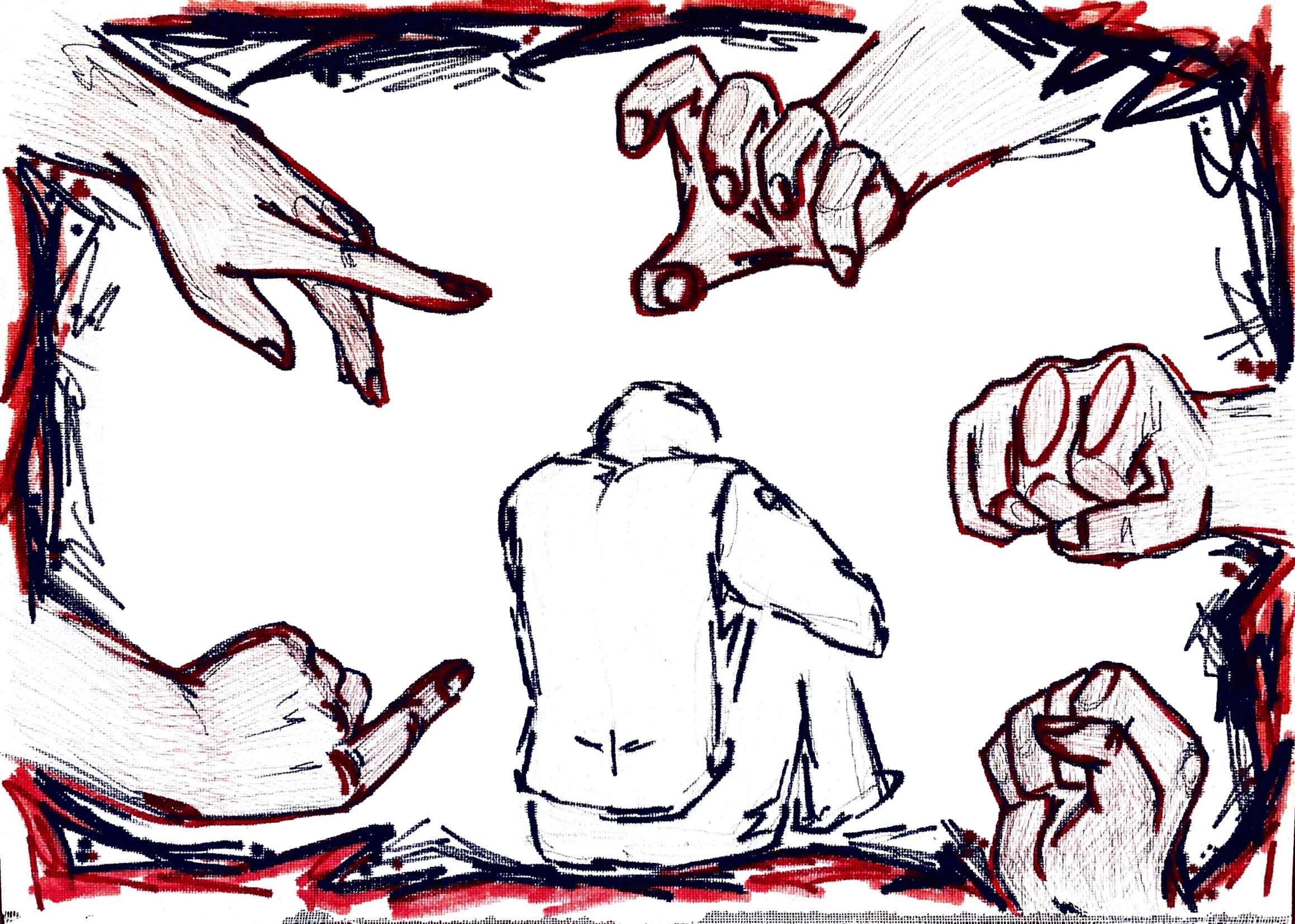

“Soon after arriving in Tbilisi, I realized that there was danger at every step, and I shouldn’t have faith in anyone. The instinct of self-preservation led me to stand up, engage in sex work, and sustain myself independently,” she says. “Even in the LGBT+ community, everyone wanted to get ahead, to prove their superiority over others. The cisgender women who worked at the circus area were resentful, and we had to deal with them.”

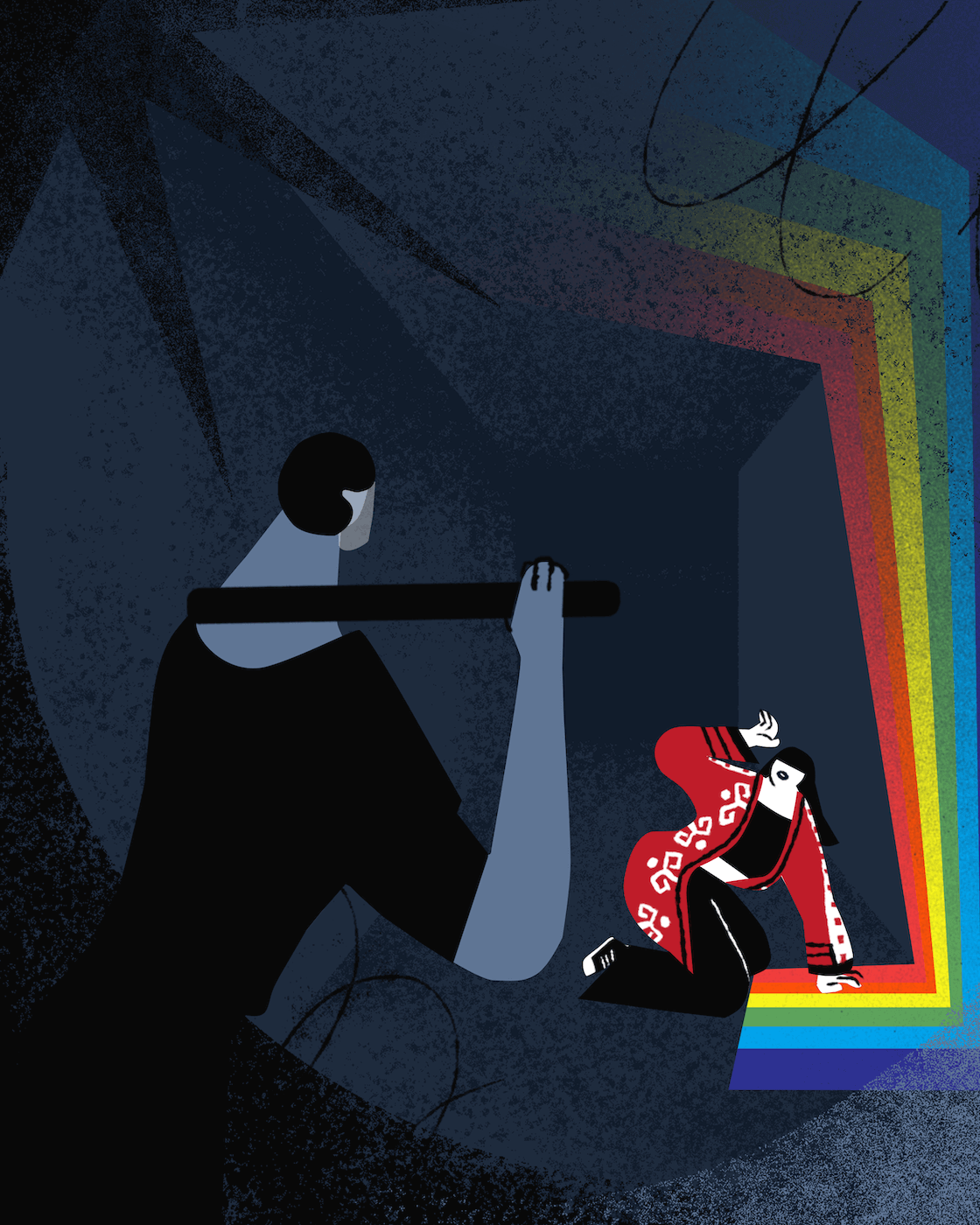

She recalls a time when women engaged in sex work, especially trans women, were exploited by all sides, from the police and political groups to men sent to attack them by cisgender women.

“Those people, particularly, benefited from exploiting queer people who were not out. Many people who were engaging in sex work were constantly terrified because their family members were unaware of their gender identity or sexual orientation, forcing them to live a double life. Members of criminal groups could easily blackmail them, force them to agree to sex, or use them to assert power,” she recalls.

“I lost everything, everyone dear to me and had nothing to lose, nothing for them to scare me. I was out, underage, and could use police protection for me or others around me — trans women who were constantly beaten and insulted, and gays who were subjects of humiliating attitudes from the other members of the community. I had to fight all the time, and I don’t even remember much from those years. My memories have faded.”

Nata traces her fingers along the wounds she received from street fights and explains that it taught her the value of knowing one’s rights and the necessity of being as direct as possible when interacting with the police in order to get their attention and urge them to take action.

“Selective approach is the one of many problems; if we conduct an experiment, go out and call the police separately about an attack, you say you’re a journalist, and I say I’m a transgender woman, we’ll see which one they respond to quickly,” she says.

Georgia passed an anti-discrimination law in 2012, which includes a number of protections for LGBTQI persons, however its efficacy is still up for debate.

A 2019 survey conducted by the Tbilisi-based non-government organization Equality Movement found that 11 out of 18 respondents had interacted with law enforcement officers. All 11 reported that police treatment was demeaning and abusive.

Today, the threat of daily attacks is much lower compared to the past and public surveys show positive changes in how society views LGBTQI people. A 2021 report by the Tbilisi-based Women’s Initiatives Supporting Group found that attitudes towards LGBTQI people in Georgia improved compared to 2016. For instance the number of people who perceive talking about the LGBTQI community’s legal equality as “propaganda” and “pushing their way of life on others’ ‘ reduced from 66.5 percent to 55.9 percent in five years.

However, problems and threats remain very real.

In the months of May and July, queerphobia is at its peak, especially around Pride Week, celebrated the first week in July. This year the closing ceremony was disrupted by far right protesters, and violent groups attacked journalists covering Pride Week in 2021. The organizers of the attack have yet to be punished, and only some of the attackers have been charged. Furthermore, the leaders of an aggressive, pro-Russian group, Alt-Info, continue to issue violent calls and openly threaten those who spread “propaganda of depravity.” Over the past few months, private businesses have come under attack for spreading queer “propaganda.”

Trans people in particular have struggled to find security and sustainability. It is difficult for them to secure jobs or pay for hormone therapy, hair removal, or plastic surgery. These “luxuries” are particularly crucial for some trans people to visually align with their own gender, but priced at $12,000 to $20,000, the procedures remain out of reach for most.

Many of the trans women Nata grew up with in Tbilisi either left the country or were killed because they did not receive the support they needed. For instance, her friend Sabi Beriani, a 23-year-old transgender woman, was murdered in Tbilisi on November 11, 2014. Another trans woman, Zizi Shekhiladze, died on November 23, 2016, as a result of injuries endured in Tbilisi on October 14, 2016.

“You had no time to mourn or unwind. After just a few days, you have to start all over again, otherwise you wouldn’t survive,” Nata says.

“When Sabi was killed, I was in Turkey and it was hard for me, but it was even harder when Zizi was killed…I started looking for pepper spray, life started again, I blocked out all the emotions I had felt up until that moment. For the past 15 years I’ve always carried pepper spray, even in the most peaceful places.”

By 2016, Nata decided to work with non-governmental organizations to support the queer community and work with people who needed help. As Nata says, her personal experiences helped her to better understand others in need.

“I know what it’s like to live on the street when no one is there to support you and you don’t have a family to lean on to. There have been times when those I’ve helped disappoint me, but I chose to turn a blind eye just because I understand them.”

She started at the organization Identoba, which was dissolved soon after she joined. She then started working as a coordinator at the Women’s Initiatives Supporting Group. Over the years, she says she realized that most of the people she has helped cannot develop because they spend all their energy simply surviving.

“How are you supposed to think about self-development when you have to constantly think about making a living?!?,” she asks. “It’s more challenging to fit into a different schedule when you work as a sex worker, and at the same time you have to deal with mental health issues, lack of motivation. You need a supporter who won’t let you stop and will motivate you. Even some of the trans women who are able to work in different fields get such dismal salaries that they are forced into sex work.”

In Nata’s scenario, in addition to personal concerns, she has to think about other people’s problems as an activist, which frequently leaves no room for anything else.

“I started learning English, but quickly discovered that I didn’t have any resources, so I left. Constantly concentrating on your own and other people’s issues makes personal development or personal life impossible. You reach a point where no one wants to be in a relationship with you. It’s like a dead end.”

Along with having fewer possibilities for romantic connections, trans women, according to Nata, find it much more difficult to develop a connection with people, to trust, and often the relationships are far from honest.

“Perhaps because we often do not have a relationship with our family, we lack warmth and connection, so we forgive those who give little attention. Such relationships tend to be less honest, with the partner trying to ‘use’ you. For example, sex is less essential to me; I am looking for a housemate with whom I can talk and share emotions, share the responsibilities and with whom I will not be constantly in the role of caregiver — but I haven’t met such a romantic partner yet.”

Nata manages to live independently by working multiple jobs as well as various projects at the same time, but it is difficult and does not leave any time for a personal life.

“I work on a variety of projects, mostly on little pay, in order to support myself. It’s unfair since I’m one of the most visible trans activists with years of expertise, yet I’m always worried about money,” she says. “Many people, however, do not have even that. Even temporary housing for queers is not designed to meet the needs of trans women. What should they do if they are unable to work at night? Furthermore, there are no appropriate services focused on empowering trans women and providing them with the knowledge they need to be economically empowered.”

“Confrontation, division between LGBTQI organizations weakens the community,” Nata explains, noting that “when especially visible events are planned, it is necessary to listen to the ideas, needs, and opinions of the community so that they do not feel isolated from the process. We should assess the dangers carefully, in order not to jeopardize the community’s interests.”

After years of activism, Nata decided to find different ways to protect LGBTQIA+ rights and spend less time working as an activist.

“Progress is slow, but I hope we will be able to build a country in which people who left can return without fear of being hit with a stone,” she says. “Personally, my goal is to have my own house, possibly somewhere in the quiet village, where there are fewer people.”

Until that day, Nata is using the stage and her power as a storyteller to build bridges between the queer community and wider Georgian society.

“I can’t deal with all the crying, so laughter sounds good to me. I never imagined that some people would discover that they had been victims of sexual violence after listening to my stories, some of them were embarrassed to share their experiences, but my monologues helped them to open up,” she says, noting that her performances are so unplanned she normally does not even remember the conversations afterwards.

“The topics of discussion are purely unplanned. I accumulate stories from my personal experiences or conversations with friends — so there is always something to talk about… and so a conversation is born.”

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect