“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

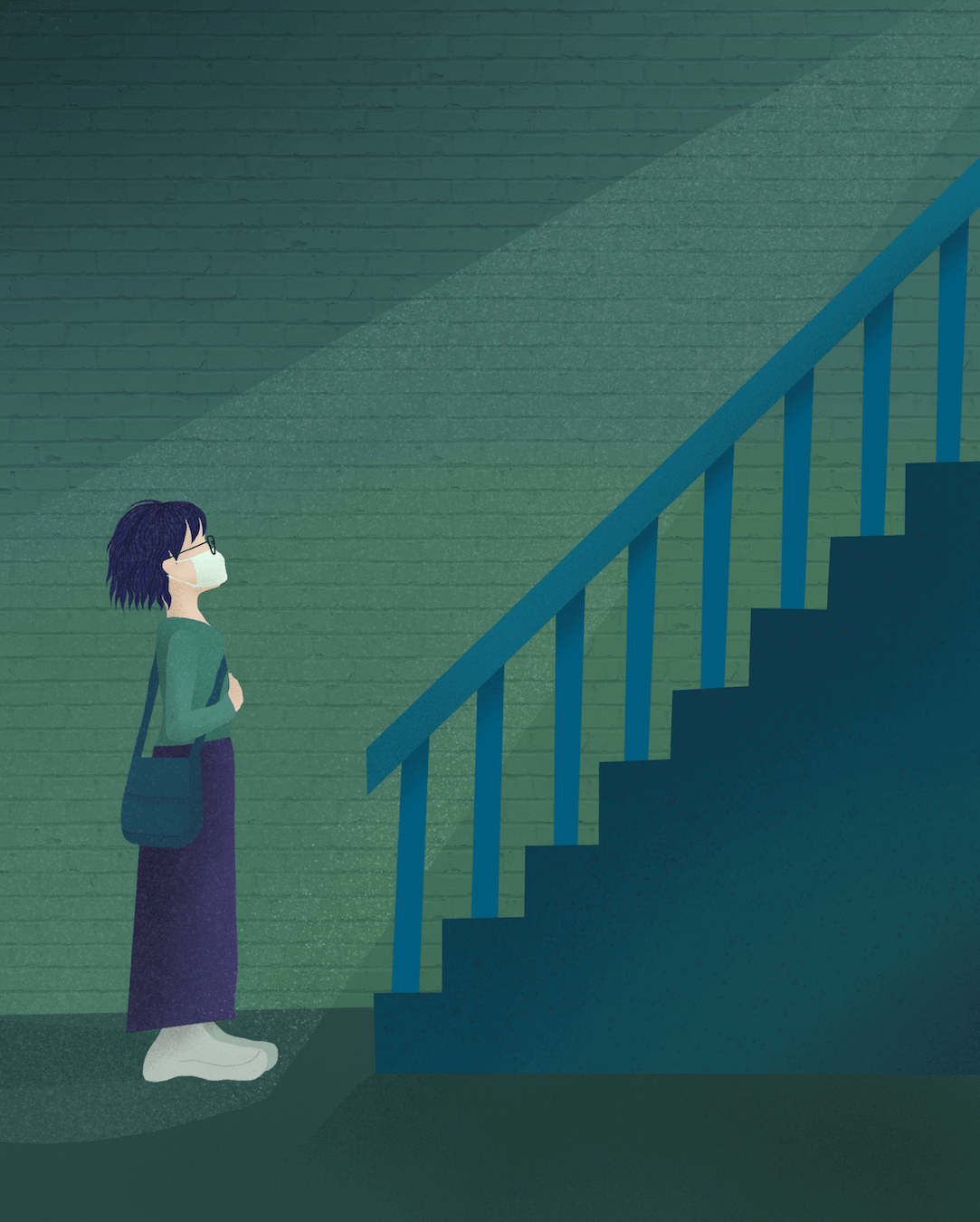

Aigul K.: “Focus on the next step, not the whole staircase”

Please introduce yourself.

I am Aigul K., 22. I have a law degree and I am currently working as a teacher’s assistant. I want to work in my profession and build my career.

Tell us about your sexual and gender identity.

I am a non-binary, gender-fluid person, and my sexual orientation is lesbian.

Could you describe your disability?

I have several chronic autoimmune diseases, arrhythmia, hypermobile joints and ADHD.

What’s it like to be a queer person with a disability in Kyrgyzstan?

Feels quite lonely. It feels like I can’t be fully accepted by any society. Because my disability is invisible, people just perceive me as a perfectly healthy person who just ‘acts weird’.

That’s why they put labels on me: people think I am lazy, not a person who is in pain, who is tired every day and tries their best to get on. Ableism and homophobia are so commonplace that society doesn’t even realise how accustomed it is to excluding disabled people from many things.

I have a certain sense of not even belonging to the queer community. I am one of the very few people who still accept the pandemic as a new reality, so I am vaccinated and wear a mask – my condition makes me vulnerable to sickness. However, masks work better when everyone wears them, and I rarely meet people who still wear masks regularly, which gives me the feeling that people around me do not care about my health, are willing to exclude people like me from many areas of life, and are unwilling to take measures to improve the safety of people with low immunity and those who are likely to suffer infection with long-term consequences.

What challenges do you face in your work as a queer person with a disability and how do you handle them?

I felt the difficulties at my very first job interview. The interviewers immediately became tense when I told them I had a health problem. Also, because of ADHD, I stand out and people perceive me differently, they think I’m weird. That’s probably why I couldn’t fit in.

How have queerness and disability affected you as a person? Where do the two parts of your identity intersect? What conclusions have you been able to draw?

First of all, because of ADHD, I have problems understanding my feelings and emotions, so it took me a long time before I realised I was queer.

It is also very hard for me to open up to other queer people about my health, I feel like I will be judged or people will stop talking to me, so just a few people are aware of my condition.

To be satisfied with your life, what are the needs that you have that are not being met in your country? What is missing in Kyrgyzstan?

Many things are lacking. There is a lack of safety for people with low immunity and a lack of awareness of the problems of people with disabilities, especially those with ‘invisible’ disabilities. When people hear ‘a person with a disability’ they think of a person with a mobility aid (wheelchair / crutches / cane etc.), not a person who looks exactly like others but has special needs. And hardly anyone can imagine a queer person with a disability, people just don’t think of us.

What or who has helped you to carry on, to live and to grow?

My friends support me every day, believe in me when I face a wall and never judge me, for which I am eternally grateful.

What advice would you give to people with a similar background?

Don’t give up, you’re not alone, even if you feel lonely. Don’t put too much pressure on yourself. The fact that you have survived another day is a real victory.

Zeé: “Just do it with love”

My name is Zeé. I’m a creator, a blogger, an influencer, and a TikTok vlogger. People also give me other labels. I don’t try to hide my queerness, instead, I use it as a tool to tell stories employing ‘affectation’ and language associated with queers. I’m a media expert, a content writer who advises big companies and bloggers on growth and creating content that goes viral. In short, I’m popular, girl 💅🏻

I identify as a non-binary person. In terms of sexuality, whatever goes. That means I don’t have an attachment to a particular gender. It depends on the person.

I have infantile cerebral palsy. It is a childhood disability, it is not acquired. I was injured at birth. As a child I couldn’t walk, I was dragged around, but physiotherapy helped me to get on my feet. That is how I am today.

On being a queer person with a disability in Kyrgyzstan

You become part of two vulnerable groups, and social pressure is doubled. No allowances are made. You get the disadvantages of disability and the disadvantages of being queer at the same time. When it came to expressing basic things, there was some physical overlap.

When I was a child, there were things I couldn’t do because I was ashamed. When you are ashamed of your disability, it has a cumulative effect. Emotionally, it’s hard to shake off, and all those traumas and limitations carry over into adulthood. I spent my teens getting used to the impact of disability on my life. The queerness manifested itself at the age of reason. In short, I’m like ‘Nescafe: 2in1’ or Hannah Montana.

People with disabilities are treated with pity. When one helps people with disabilities, they feel like heroes: “Look, we have a disabled person working here, give us a pat on the back”. I don’t feel any social or commercial barriers in that respect.

Of course, being queer hinders my financial and professional development. I am becoming popular, but my personal indicators of success are hard to reach. I’m losing ad offers because of my queerness and freedom of expression. My colleagues respect me, but when it comes to clients, my pool of opportunities shrinks considerably.

On queerness and disability

I perceive my queerness not so much in terms of sexuality but rather of gender identity. It’s a determining factor for me in how I move in this world, how I perceive my appearance, and how I relate to my body. Sexuality floats and changes over time and I don’t ‘pin it down’.

Disability, on the other hand, has produced a lot of complexes, traumas and constrictions that I am still dealing with. When I start relationships with people, or when it comes to sex, I have to teach the person: to explain where the boundaries are, what is comfortable, and where there is no need to be shy.

To be satisfied with your life, what are the needs that you have that are not being met in your country? What is missing in Kyrgyzstan?

Compared to other people with disabilities, I am mobile and quite privileged. I will not break it to you if I say that on a social level, I would like to be accepted, not tolerated. We don’t need to be tolerated, we need to be accepted.

What or who has helped you to carry on, to live and to grow?

It wasn’t until I was an adult that I understood my parents’ upbringing strategy. It often happens that when a child has a disability, they are pitied and not allowed to do much. In my case, I did what my brothers did. I never felt deprived or special. I was given a healthy attitude as a child about who I was and what I could achieve. That’s a credit to my parents.

Relatively healthy self-esteem and the understanding of “Oh my goodness, I can do a lot” helped me to gradually gain confidence later on.

What advice would you give to people with a similar background?

If you have inhibitions in your head, anxiety, problems, if you don’t want to accept anything new, to compromise or take risks, to change, then really go and see a therapist. I don’t know anything better than therapy. Most people with disabilities desperately need it. People with disabilities, especially in our region, are very traumatised. Even ‘invisible’ disabilities imply certain traumas. Therapy is needed to understand your mental weaknesses and strengths.

It is important not to give up and to be as open as possible to new things.

Rapunzel: “There are things one doesn’t choose”

I used to have long blonde hair, but when disability came into my life I had to cut it short. My people joke about it and call me Rapunzel. I’m 25 years old. I’m a young woman with a disability. I use exactly that phrase, I am not ‘disabled’, and my abilities are not limited. First of all, I am a girl and disability is just my status. I am involved in project management. I also volunteer in several initiatives that support young people with disabilities. My lifestyle is dynamic, I have a higher education in a field that is useful for my work, I travel, I even publish scientific articles in magazines, I volunteer, and I am an organiser of many cool events.

I’m a cisgender woman. Bisexual.

I have an acquired disability – cerebral palsy caused by a viral neuro-infection and complicated by a brain aneurysm. I was about 10 years old then. It just happened and divided my life into ‘before’ and ‘after’. A long period of rehabilitation followed. Now, after a long journey of pain and trials, I have survived. I don’t run or dance like I used to, but I live a full, free, independent and fulfilled life.

On being a queer person with a disability in Kyrgyzstan

Perhaps because I don’t want / need to be out at the moment and am a ‘closeted’ bisexual person, I don’t generally encounter the problems that openly queer people face. In the LGBTQ+ community, I have never experienced overt discrimination because of my disability. I don’t know exactly how many queer people with disabilities there are in the community, maybe not that many, and it doesn’t make sense to choose a party venue with a ramp or an accessible toilet, for example. But there is a big problem with the inclusivity and accessibility of a lot of community events. That aspect is not given enough attention.

Harrow and alas, I encounter discrimination, stigma and stereotyping about disability all the time outside of the community. It seems to me that everyone understands everything.

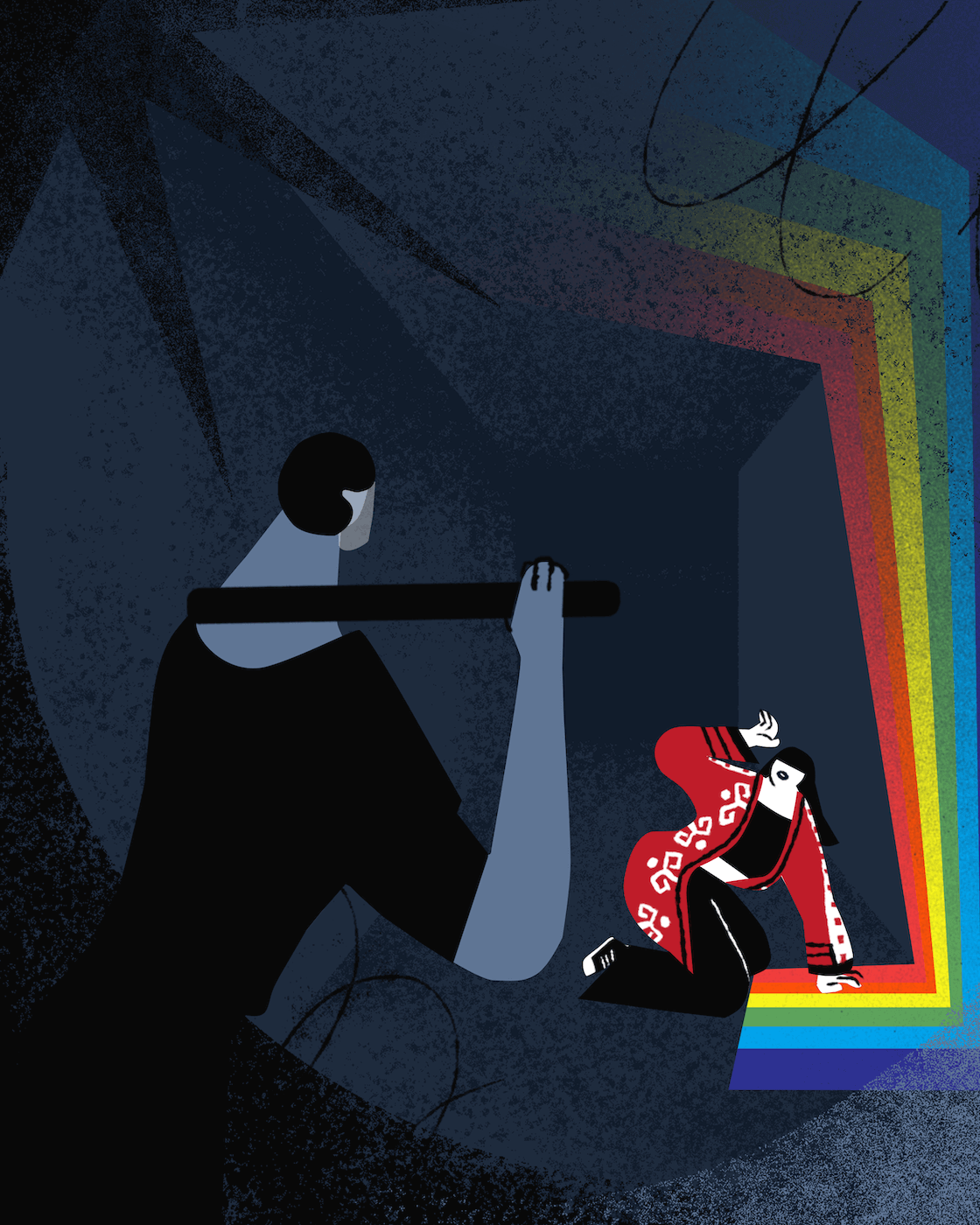

I want to talk about relationships, it is very difficult to find a partner for a queer person with a disability. Many potential candidates are simply afraid of the responsibility. Afraid that I’ll need support, even though I’m quite a self-reliant person. Probably, they are afraid that I won’t always be able to (physically) help them. I’m talking specifically about the relationship with the girl who broke my heart. This is where I experienced discrimination based on ability, not so much from her as from her close friends. She and I were doing great up to a point when I met her terribly toxic company. These people were looking me in the eye and saying, “You’re a great couple! She takes such good care of you!” while gossiping about me behind my back, “Honey, why do you need this handicapped girl?”. It all happened the way it was supposed to. Honestly, I was very much affected by the experience.

On queerness and disability

I have a strange relationship with my disability and queerness. I have to say that it has greatly influenced certain attitudes and my worldview. Without the disability, I would not have acquired most of my current life principles. Because of the disability, you just start to see the world differently. You start to see things that are in the background for others. You see much more flaws in the world than the average person, and your sense of justice is sharpened immensely.

Your worldview changes once and for all. And you suddenly start to notice discrimination not only against people with disabilities but also against women, LGBT+ people, people of colour. You start to question not just your ‘beloved’ state, but society as a whole; you start to care not just about your life, but about the world.

To be satisfied with your life, what are the needs that you have that are not being met in your country? What is missing in Kyrgyzstan?

Again, it comes down to inaccessible infrastructure. As a woman with a disability, I face many challenges. Sometimes I can’t go to the places I want to go. I can’t use public transport. There are times when I can’t use the toilet. I could go on and on about the needs of a person with a disability that are not met in Kyrgyzstan: education; a decent job that pays a decent wage; respect for my rights. Speaking of queerness, there is of course ‘covert’ discrimination, aggression, manipulation and stereotyping of the whole LGBT+ community. And the fact that I can’t speak openly about this side of my identity is in itself indicative of discrimination.

What or who has helped you to carry on, to live and to grow?

Of course, my mother, who is always by my side, was the most engaged. She has supported and encouraged me in all my endeavours, even the craziest ones. My psychologist is generally one of the best people in my life, who also introduced me to a stranger girl with a disability that I was. Many thanks to my friends with and without disabilities, I couldn’t have done it without them. The Kyrgyz Indigo team, especially one staff member I met at a human rights training. I have become friends with her and she has started inviting me to various community events.

Most importantly, I am grateful to myself! I was the one who helped me to go on and to live instead of existing!

What advice would you give to people with a similar background?

In general, mental health is a priority. For everyone, for able-bodied people, for people with disabilities, for queer people, etc. Take care of your mental health!

Also, although the experiences of different people with disabilities vary, a sense of community can help people with disabilities cope, especially given the systemic barriers and stigma that persist. Accept and respect yourself, accept and respect the uniqueness of each person and see everything as a natural and beautiful part of human diversity, including disability and queerness and beyond.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”