No Trauma, No Drama. Rewriting Media LGBTQI+ Narratives

Nora`s shoes, Yerevan, 2018, photo by Diana Karapetyan.

“The media still loves representing the image of queer people as lost, dramatic… often without money and basically at the very low point of their lives,” notes Nora Petrossian.

“But when things are different, they’re not interested anymore.”

Nora, 24, a professional dominatrix, experienced the power of the media at a young age. He was just 18 when he ran away from an abusive family. His story was widely reported in the Armenian media, often focusing on the trauma and sensationalism instead of his ability to survive and thrive.

Nora Petrossian in Yerevan, 2021, photos by Artem Mikryukov.

“If I’d write about myself, I’d tell how a young 18-year-old boy, who escaped his home and left behind his family, which was abusing his identity and choices. Who slept on the street because he had less than $10 in his pocket and in just one month pulled himself together, rented an apartment in the city center, and turned his passion into work for life!” Nora says.

“There was no prostitution, crimes, and drugs involved, nothing that the media usually loves showing… It is important to show a different story, also because it affects the people within the community who read them. They need to see themselves succeeding, healing, and moving on… They need to know that it is also a possible line in their story!”

Nora notes that reporters lost interest in his story once he started to live a fulfilling and happy life.

He recalls one story published by the well-known Russian media outlet “Dozhd”, which began with the line, “It’s not the good life that forced the transgender Nora to become a prostitute.”

“It’s just weird to talk to people sometimes tell your story, and later see that nothing of what you said was heard,” he continues, adding that he is a cisgender male who has worked as a dominatrix for over eight years and can’t really understand how the interviewer could misrepresent him in that way.

“Often whatever you say is turning into this dramatic clichéd version of your life, which more matches their perception of your reality or how it should be,” he notes.

“Once I started to change, and I think I have a better life, healthier one, with stable relationships, successful work, and my own NGO, it stopped interesting them — maybe because a good life isn’t a ‘hot topic’ and provokes no one.”

Today Nora lives in St. Petersburg, Russia with his husband. He runs a successful dominatrix business in Russia but unfortunately left behind running his NGO “Fearless” in Armenia, mentioning that it showed him the dark competitive side of the NGOs working in the LGBTQI+ community in Armenia, and he preferred shutting it to no longer see “how people put each other down for receiving grants,” as he notes himself.

“Yes, people in Armenia are aggressive sometimes, but mostly they are like that when they see you’re weak. And mostly I started understanding that many of their reactions come from poverty. Yes, yes, they see me in nice clothes, resting in nice places, and immediately comment something bad not because they’re necessarily homophobic, but because they haven’t rested for some 10-15 years,” he says.

“Of course, my profession, which to me is a more extensive, tough form of therapy, is often seen both by the media and society as prostitution. I’d love people to understand more what it really is, but I guess that’s another story.”

Nora notes that after three years of running his NGO “Fearless”, he eventually left the organization. He believes the breakdown in communication can run both ways.

“Many clichés and misinformation are still circulating in society because our community itself is not really communicative. There is a gap between society, simple people, and our community, that often gets bigger with the policy of different NGOs, which are like…fueling a sense of seclusion from society,” he says.

“People from our community sometimes see themselves from such a self-marginalized, victimized position, that they perceive everything from that prism, even if it has more things to do with their improper actions in public spaces, where objectively anyone could be criticized.”

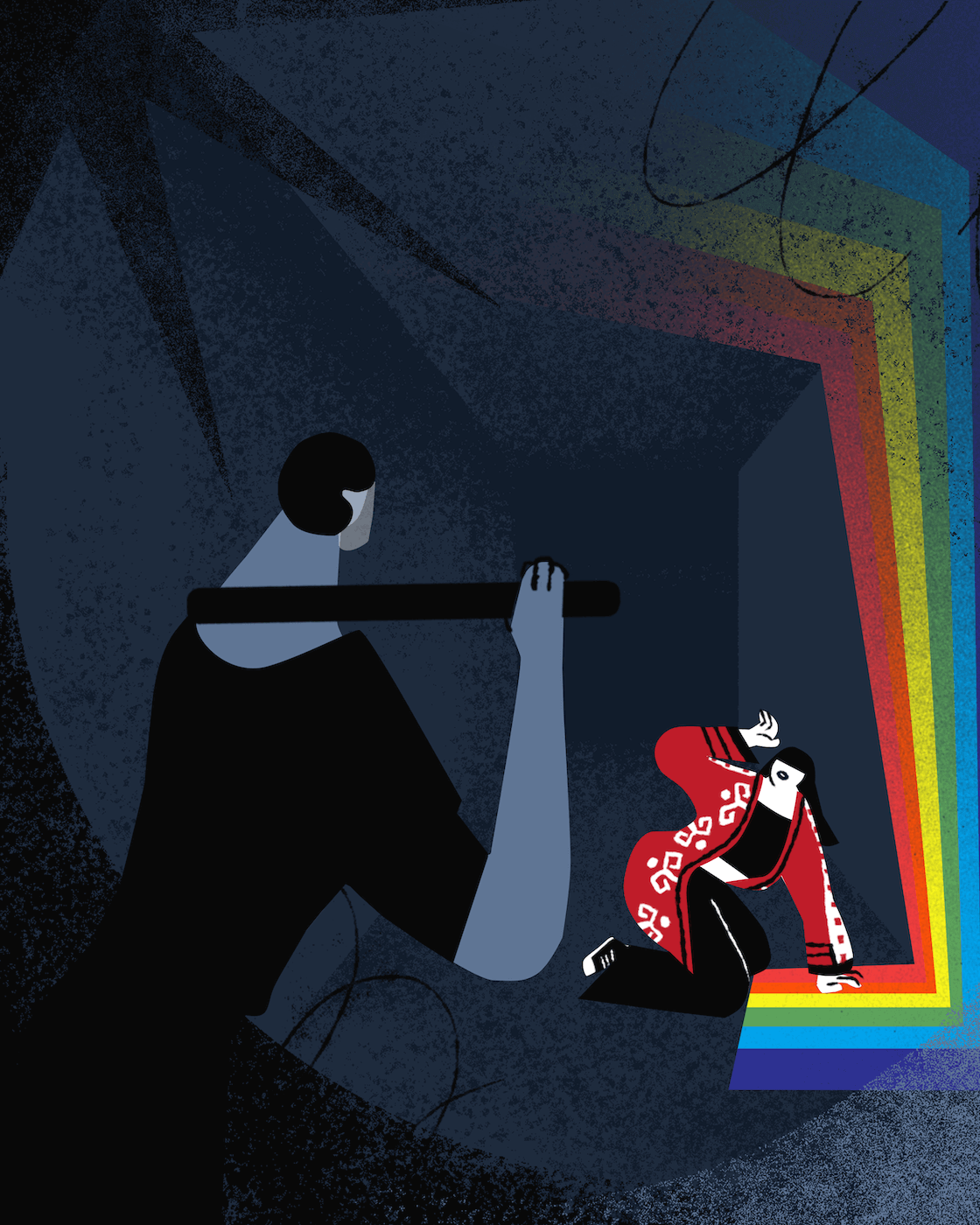

Stills from the project “Save the date” photo courtesy of Mischa Badasyan.

Mischa Badasyan, 35, an ethnic Armenian born in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, is also trying to empower Armenians through his animal rights activism, art, and social work in the field of migration and refugee support.

Although based in Zurich, he focuses on the general taboo of being different that exists in Armenian society. The fear of otherness runs so deep that his family does not accept the fact that he became a vegetarian at the age of 17.

“I was born into an Armenian family and grew up in post-Soviet society. Both mean pretty conservative structures and old frameworks of life,” he notes.

“I left Russia when I was 20. Up until that point, I didn’t come out and I never talked to anyone about being gay. All this led me to move away and enjoy my freedom in Europe.”

Since starting his life as a gay man in Europe, Mischa has gained international attention through his art, especially his performance art piece “Save the Date,” which explored the themes of LGBT, and loneliness through his experience of having sex with 365 men over one year.

During the project, Mischa began receiving threats from Armenian nationalists, who accused him of “damaging the image of Armenians.”

Mischa says the experience didn’t deter him from activism but instead reinforced his belief that Armenian culture connects the idea of Armenia and being an Armenian with “drama and pain.”

“People are stuck in the past and don’t know how to deal with reality. Any criticism is not welcome. You are not allowed to criticize your homeland,” he says, noting that some nationalists see everything as a threat to their vision of reclaiming Armenia’s historical borders but no one pays attention to real issues in the country, like working plumbing or decent roads.

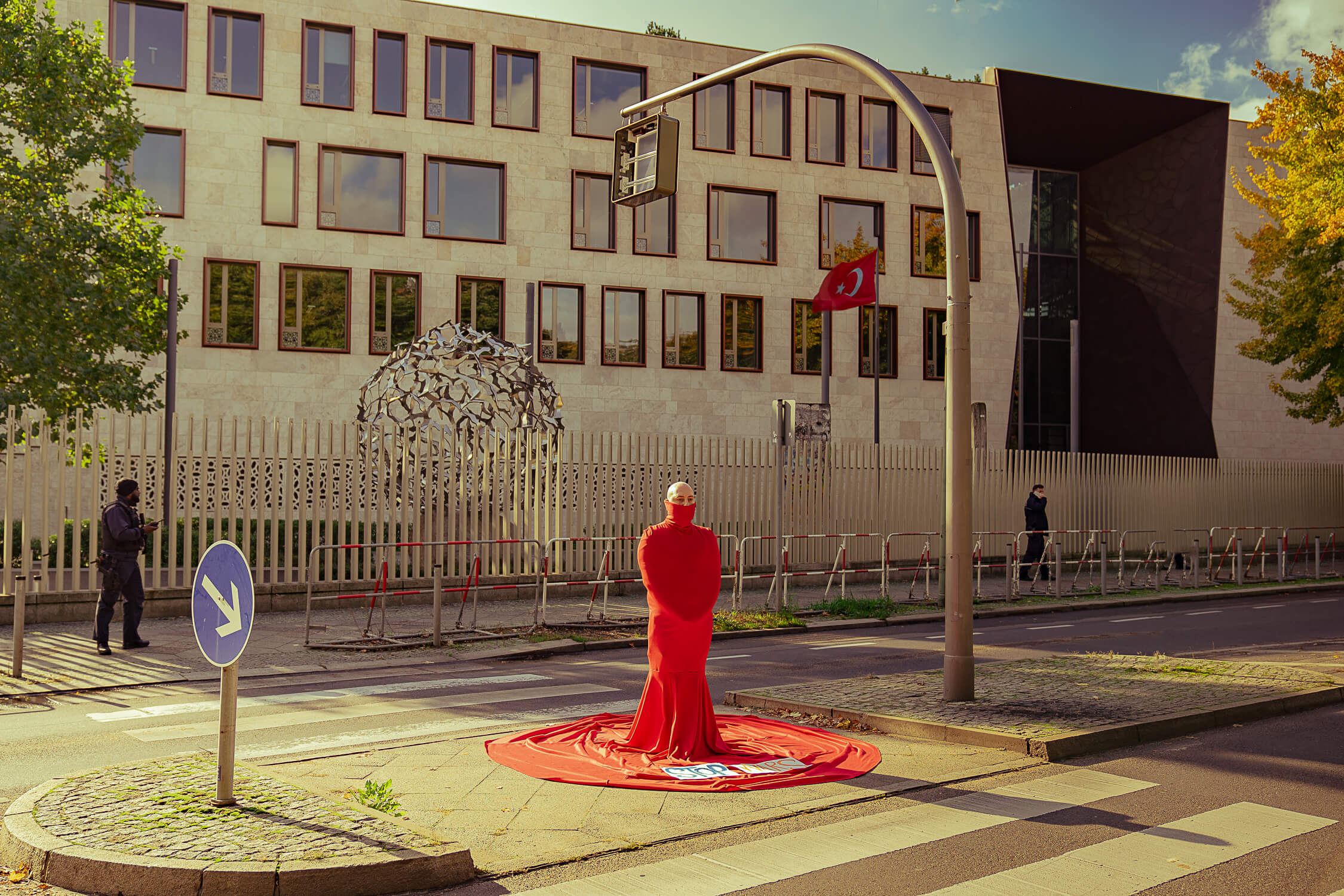

STOP WARS! Performance in front of the Turkish Embassy in Berlin, photo by Abdulsalam Ajaj , photo courtesy of Mischa Badasyan.

After years of dealing with topics like depression and cultural discord, Mischa says today he is focused on empowerment and issues that bring people together, like animal rights.

He is currently supporting animal shelters in Armenia and promotes environmental responsibility. “I realized those souls receive little from this world even though they give 100 percent of their love to us.”

Photo courtesy of Mischa Badasyan․

Nora believes the key is to help people find a common language and promote equality in society through education and engagement.

“You can’t just demand a good attitude towards yourself, if you treat people like enemies, or try provoking them when they are more bothered by your social behavior than your gender identity,” he says, adding “I believe if you want to be part of society, you have to see yourself as part of it. Otherwise, with your actions, you are really proving that this image of a crazy, drug-addicted, sex-starving transgender male who provokes people is actually true. This way you make the society see our diverse community only from that perspective,” adds Nora.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions