The Great Mothers. LGBTIQ+ and feminist characters in Kazakh fairy tales

As someone who questioned and accepted myself as a lesbian in my teens, I was a lonely child. I could not find fairy tales or legends in Kazakh literature that reflected my quest and showed the image of a strong and daring girl. All I came across were batyrs (Kazakh horsemen warriors – ed.), tricksters, khans, magical animals, and viziers. I can hardly recall any female characters, though I read a lot. I won’t even talk about classic Russian literature, because reading it did not make me feel better.

The world literature, which I read as part of the school curriculum, also did not stand out very much: there were very few stories with female leads. I came across queer fairy tales much later, but I am not disappointed at all. I often share these discoveries with my acquaintances and friends. I use the stories as examples when talking to people who attack the LGBTIQ+ community.

After all, according to opponents of gender diversity, Kazakhs had no practices other than heteronormative, heterosexual ones. However, as I found out, that was not like that.

Let me tell you this in order.

Ambivalent monstrosity

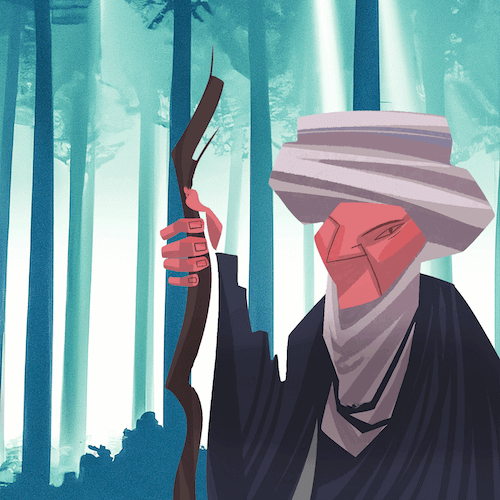

Famous Zhalmauyz Kempir, Zheztyrnak and Albasty appear in many Turkic myths and legends. They are the beings of the lower world who bring death, failure, and misfortune. Their resistance to the established order (attacking batyrs, eating human meat, sucking the blood of girls, living away from people) is presented as a negative thing. Asima Ishanova, Ph.D. in Philology, professor at L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, commented on the image of Zhalmauyz:

“I think the monstrous female characters of Kazakh folklore are rather ambivalent, ambiguous. This ambivalence is felt in Kazakh mythology and folklore, as well as in world culture. The archetype of the Great Mother, woman (Baba Yaga, Kali) – they are destroyers and liberators, bloodthirsty and wise, kind and cruel at the same time.”

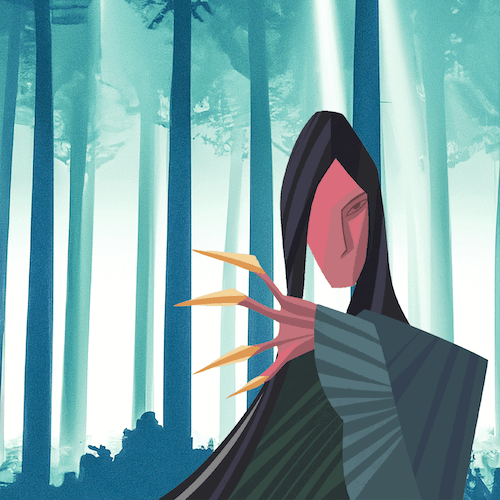

Zheztyrnak, the genderfluid shapeshifter

Zheztyrnak is a female daemon with brass claws. She is voracious, has a shrill voice and is extremely physically strong. She can also transform into an animal or take on the form of any girl. This creature often does not indicate its gender, so the traveller tries to recognise it by its clothing and appearance, and the guess is not always correct.

Zheztyrnak sneaks up and attacks a log or a stick (more precisely, she jumps and hugs it), which the hunter leaves in his stead. This episode has sexual connotations – the hunter is worried about his bodily boundaries being violated by a man. If Zheztyrnak appears in a female form, the hunter is easily tempted and enters into a sexual relationship with the creature (even if his wife is waiting for him in the village).

Zhalmauyz and Zheztyrnak vs. Baba Yaga

Russian-language literature from the Soviet period notes that Zhalmauyz or Zheztyrnak are similar to Baba Yaga, the demonic heroine of Slavic folklore. This is a very superficial and colonial comparison. Zhalmauyz Kempir holds traces of shamanism. She is the mistress of the family hearth and the guardian of the “death land”.

But what distinguishes the demonic woman from all other female characters? In almost all fairy tales, she gives fire back to a girl who had it negligently extinguished. The girl pays by letting Zhalmauyz suck blood from a toe or knee. This action can be interpreted as an intimate sexual act.

The norm-defying Albasty

These examples show that fairy tales contain illustrations of irregular gender roles and perceptions of Kazakh society. It was not all so straightforward.

Fairy tales provide room for imagination and freedom for practices that break taboos, demonstrating sexuality, new meanings and a rejection of the conventional.

Thus, rather than being a tale of monsters and demonic women, this one is about great foremothers who gave power and potential to other heroes and heroines of legends and tales.

This article was originally published in Russian here

Nothing beats good old email

For our monthly newsletter, we pick the most important news and analysis,

and add selected content and art from queer creators.