“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

When Ali was 13, they saved pocket money from their parents and ordered an LGBTQI+ flag online. They brought this flag to their school, took a picture with it and hung it on the window.

[playht_player width=”100%” height=”90px” voice=”en-US-ElizabethNeural”]

“On the first day, only the children found out. I told those who asked that I just support it, that I myself am not gay. When I went to school the next morning, everyone in the hallway looked at me strangely. Our class teacher came up and said that if the principal finds out, they will hit me. When I went home, my mother hit me on the leg. Three people from school came to our home and told her that I was an outcast. My phone was taken away and I was forbidden to go anywhere except school.”

In the annual report of the European organization ILGA, Azerbaijan ranks last in respect of the rights of LGBTQI+.

Learning about the difficulties of queer life in Azerbaijan, young activist Ali Malikov also learned to deal with these difficulties by securing their economic freedom via writing articles on queer platforms and creating podcasts. Being able to live in a relatively safe environment due to their economic freedom, Ali has been fighting for their rights since the age of 13.

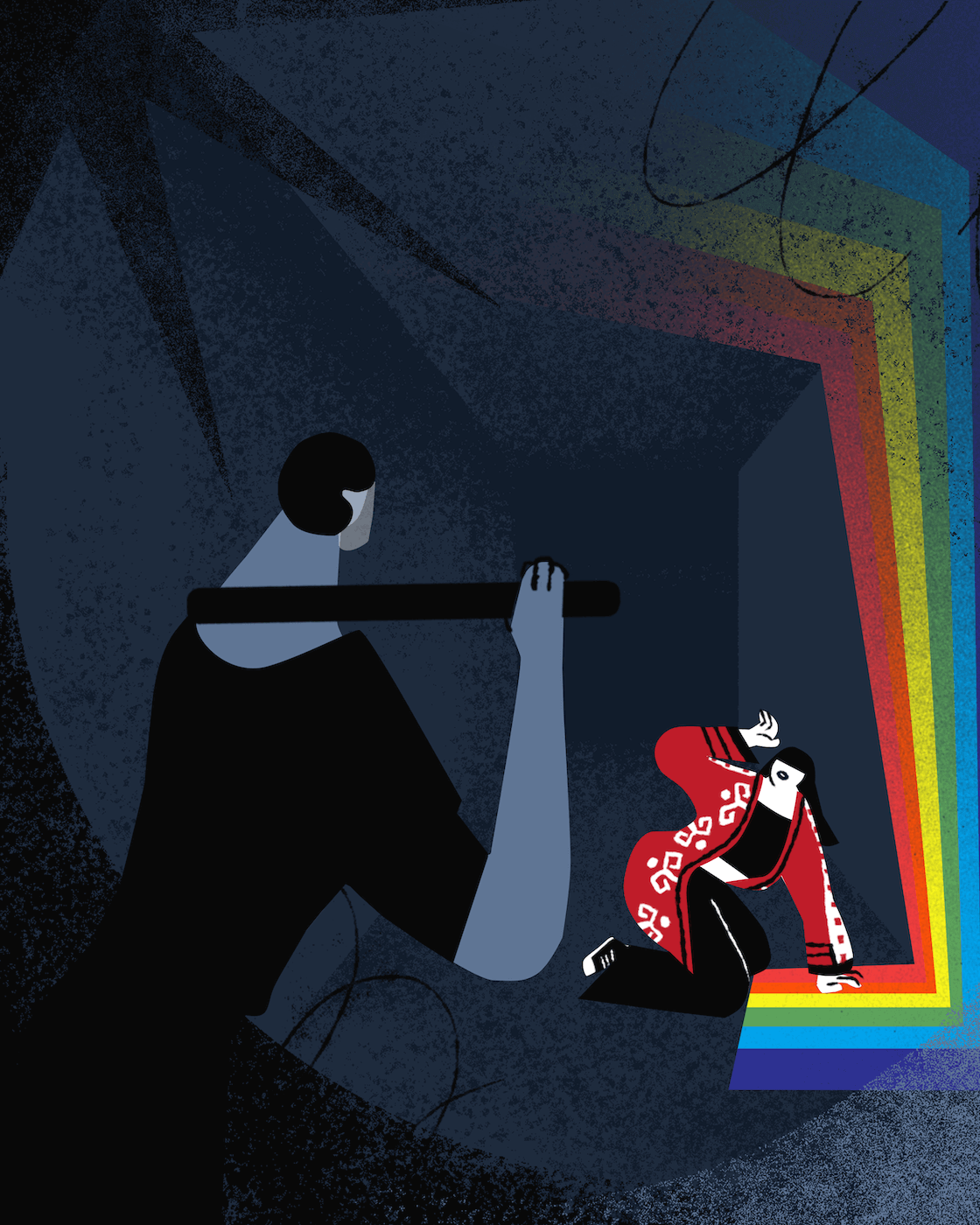

“In Azerbaijan it is difficult not only to live queer, but also to discover yourself and learn something about it. I remember when I was nine or 10 years old, I realized that I felt different from my friends, and searched the internet using the query “I like boys.” But almost no information in the Azerbaijani language could be found, so I had to read in Turkish. Since I was a child and could not fully master the Turkish language, I understood almost nothing. The only thing I could see in Azerbaijan was how the reporters of the local ANS TV channel were chasing transgender people and filming their faces, and I was very afraid of that environment. I was taught that if you are transgender, you are immoral.”

The struggle that followed the “flag problem”

“At the time, I had an Instagram page called LGBT Azerbaijan. Since my phone was taken from me, once a day I secretly took my sister’s phone and shared a post.

“At school, my teachers tore my notebooks and lowered my grades. The children in the corridor, looking at my face, cursed, hit me and ran away. I was still in the 8th grade, I was silent, because I was a child. I studied in Binagadi, so I did not know how to defend my rights in such an environment. They spread the address of my house and my photos. My friends’ boyfriends wouldn’t let them talk to me, and they didn’t talk.

“Then I realized that for many years I had been an object of entertainment for them. Everyone considers gay people funny.

“A few years later, I met my current best friend through Facebook. It was a time when the feminist movement was very active. We created the Femkulis platform. Since we were both under 18, that was all we could do, so we shared daily news there in an attempt to raise awareness of the Istanbul Convention. Later, we started posting “free woman” stickers in the subway and on the streets. One day the police called us, and my mother and I were called to the police station. I was afraid and my mother was crying. My mom was told by the police that queers can be perverts and drug addicts.”

“For the first time in many years, I felt comfortable walking around the school”

In the 11th grade, Ali, who decided not to be silent anymore, began to talk publicly about the bullying at school. After that, they were subjected to an even sharper reaction from the people around them; the person who supported them during this period was their mother. At the age of 16, Ali gave interviews to many media platforms about the bullying they experienced in school.

“After that, I got calls from everywhere. When I contacted the Committee for Family, Women and Children, they told me to delete the status I posted on Facebook. I didn’t remove it. When I went to school, I saw that Schoolboy’s Friend and the Ministry of Education sent two psychologists to me. The psychologist sent by the Schoolboy’s Friend told me that I was provoking myself. The one from the Ministry of Education said that I need to switch to online learning. I said I wouldn’t do it. Once the Ombudsman called, but then nothing was heard from her. One day the police went to school with me. After that, no one teased me at school. For the first time in many years, I felt comfortable walking around the school.”

After some time, 16-year-old Ali began writing blog posts about queer education and gained a considerable audience of 40-50,000 readers. Later, they expanded their activism and began to take part in protests.

“After I got into activism, I realized that this is what I wanted for years, and this way I feel happier. My mom scolded me, saying that enough was enough, I became too noticeable. But I made my choice. One day I went and told my family that I was giving up on them before they would give up on me, that I didn’t like the family structure anyway. I left home and began to live separately. True, sometimes I miss my mother, but having a separate house helped my activism a lot. Now I can be more sympathetic. When something happens to someone, I can easily go out to them and even share my house if it’s someone I know.”

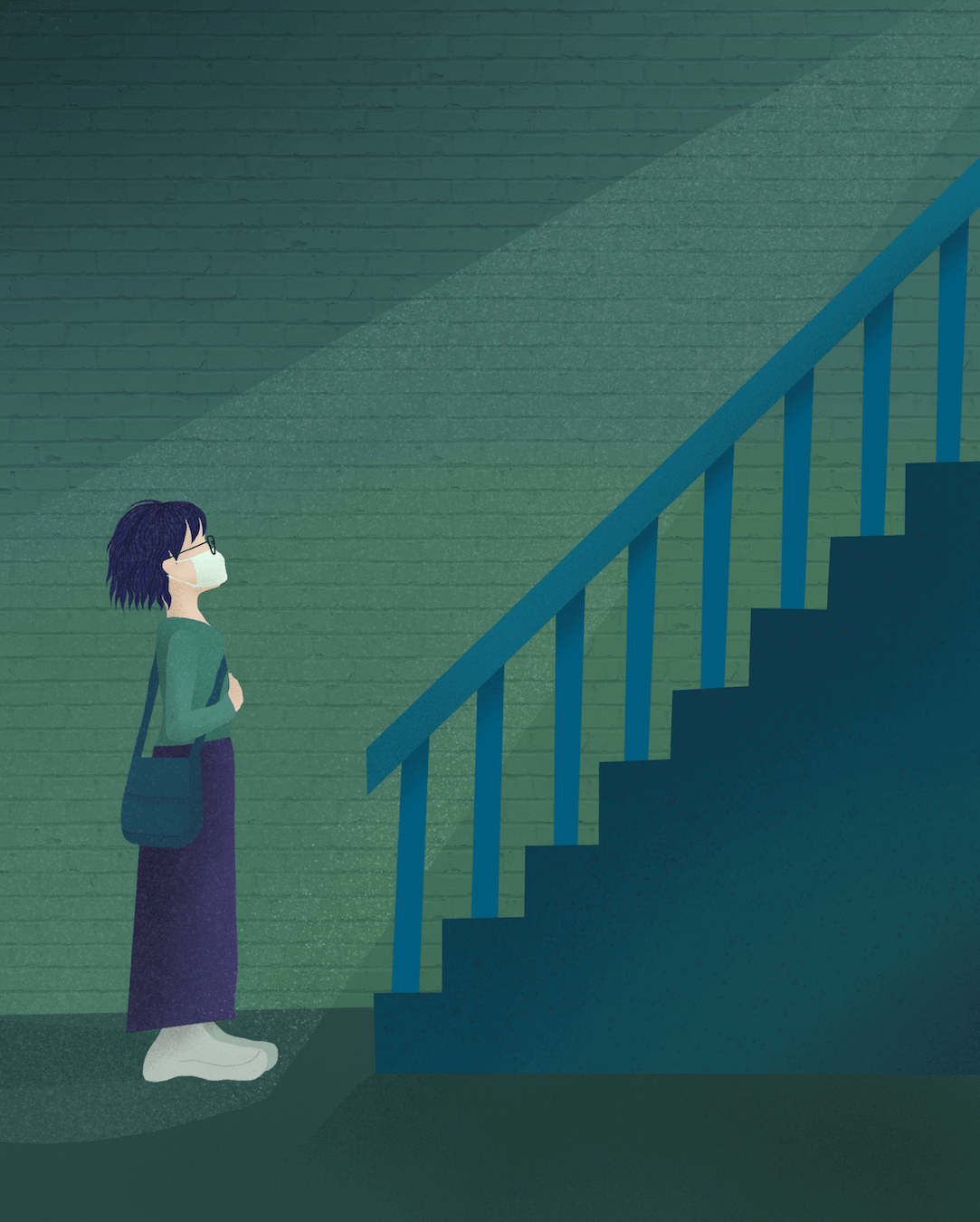

Military Commissariat in Queer Practice

In Azerbaijan, queer people are considered unfit for military service. Queers who claim that there is a gap in the law in this regard say they have “psychological problems” listed on their military ID. This can cause various problems in the future in work, in property matters etc.

“I recently resolved my draft issue and am now officially unfit for military service. I still didn’t want to join the army. In the worst case, I would have abandoned the army. I went to the military commissariat together with a social worker. The people in various structures don’t want to talk to queers, so it’s better to have someone with cis / hetero appearance with you. We are ignored as individuals. They didn’t even put me in line with the other conscripts so as not to embarrass anyone. They sent me directly to the dispensary. I went there and waited in line. Again, the social worker talked to everyone. Psychologists asked me why I wouldn’t join the army. Said I was queer and didn’t want to serve. They said go ahead. The next morning they told me to come pick up the documents. They wrote on my military ID that I had psychological problems. Every three years I have to go and say that I am still transgender and I have psychological problems.”

First Pride Month Party in Azerbaijan

On June 28, 2023, for the first time in Azerbaijan, the “Pride Month” party was held by the “Nafas LGBTQI + Azerbaijan” alliance.

“In general, we have always focused on pain in our posts and speeches. I understand that emotions are very important in activism and we learn from our losses. But we never have fun. Entertainment is also political in nature, and in Azerbaijan, indeed, our entertainment facilities are closed and limited. Entertainment venues are under serious police raids.

“We thought that we should gradually form the tradition of celebrating the Pride Month in Azerbaijan. In addition, perhaps a fun pastime will expand our social circle. Up to now we have united only around our friends who we have lost, people who have been killed. We decided, let’s finally have fun together.

“This year we also supported queer artists. We were able to talk with parents of queer people about loneliness and alienation. A queer parent spoke in a panel discussion. We also told our stories of self-discovery. Psychologists and social workers have also considered the challenges we face on the path to self-knowledge. We are moving forward on the way to organization,” Ali says.

“I want to become a point in a small story”

Ali says that what they want most is to live in a situation where queer people are more organized, able to speak out more about themselves, and where their voices are heard nationwide.

“Personally, I want to have my own space, my own home, which I would not have to change regularly. Where I could live a happier and more comfortable life with my family. Where I would be safe and people in danger could gather in that space.

“I want our fight to continue. I always tell my friend: “If your protesting hand gets tired, I will come and take your hand.” My biggest wish is that in the future, when someone starts doing activism, they can look back and say that there was an activist named Ali who created opportunities for us to continue this struggle. I want to be a part of this little history. This will strengthen us. I want to hope for salvation for my community.”

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect