What if homophobia in Central Asia is a product of colonialism?

Our society is divided into those who are LGBT+ friendly and those who are aggressively hostile. Of course, some are neutral on the issue – but I don’t factor them in because a neutral stance essentially plays to the advantage of the againsters.

[playht_player width="100%" height="90px" voice="en-US-ElizabethNeural"]

Homophobia manifests in the persecution, discrimination, and stigmatization of people because of their sexual orientation. I want to explore the ethical side of it: why it seems normal for people to hate others whose sexual preferences differ from the “accepted,” “normative,” and “traditional.” I also want to speculate about whose “traditional” and “accepted” values this term refers to.

In this article, I will discuss the reasons for this intolerance, its roots, and its relation to colonialism.

What is homophobia?

When referring to homophobia, we are talking about the discrimination that members of the LGBT+ community face throughout their lives because of their sexual orientation, which differs from the socially normalized one.

There has always been much controversy around this term. For example, some psychoanalysts contend that “homophobia” is not a pure “phobia” because the negative behaviour is not based on fear. Other experts link homophobia to xenophobia – fear or hatred of the “other,” the “foreigner” – and refer to the fear of someone different. In this article, I will rather rely on the similarities between homophobia and xenophobia.

In doing so, it is important to clarify that human sexuality is a natural – and innate – function of the human body, which develops uniquely according to one’s individual life experience. However, if human sexuality is natural and unique to everyone, why does our society refuse to fully accept this fact and continue to suppress members of the LGBT+ community on a systemic level?

The history of Soviet homophobia and prison ethics

I believe that homophobic attitudes and behaviours are rooted in our history, in the history of shaping the way we think. Kazakhstani society is still considered post-Soviet for many reasons. One of them is intolerance towards various social groups based on “otherness” – economic, social, sexual, gendered, aged, physical, and so on.

The Soviet era constructed a discriminatory attitude toward gay culture, perceiving it as criminal and forbidden. The official ban not only made the topic taboo but also fostered a culture in which non-heterosexuality was labelled with words bearing contextual meanings, such as goluboy (“blue”), rozovyi (“pink”) and tema (“being in, in the know”).

Being associated with an unattractive and stigmatized gay culture in Soviet times was shameful and dangerous – including because of the prison culture that had developed over decades, in which being gay meant being “turned out.”

Of course, the rejection and stigmatization of gay people did not emerge with the establishment of the USSR, but much earlier. If we study the beginnings of homophobia in the Russian Empire, we will find that in the 15th-18th centuries, the Orthodox Church had relatively little regulation of sexual matters. Same-sex relations were treated as gaieties and amusements rather than as a serious crime. Meanwhile, in Western Europe homosexuality was a sin punishable by death.

Peter the Great, who wanted to hack through a window on Europe and modernize Russia, adopted laws and penalties for various crimes, including “sodomy,” among other things. In 1716 he imposed new disciplinary restrictions on sailors and soldiers. Nicholas I in 1835 extended this prohibition to the civilian male population of Russia. In 1915, the tsarist regime considered an all-encompassing introduction of the Criminal Code of 1903, under which sodomy would remain a crime – but after the revolution, in 1922, it was decriminalized. In 1933, however, same-sex contact became an offence again – and even resulted in forced psychiatric treatment for gay and lesbian people.

It was in this year that Stalin signed a law that included punishment for homosexuality in the criminal codes of all Soviet republics. According to researcher Rustam Aleksander, Stalin, concerned about the infiltration of German spies into Moscow’s gay circles, started a purge among the cultural elite. Besides, the “leader of the peoples” himself hated gay people, so suspicions of espionage killed two birds with one stone.

By this time, the USSR had already established a network of penal labour camps within the Gulag system in strategically rich areas – their main purpose was to exploit these resources using prison labour. There were 11 Gulag camps in the Kazakh SSR alone – with 427 throughout the USSR. As researcher Dan Healey notes, one can only speak of Soviet homophobia after studying homosexuality in the Gulag.

Prison ethics and culture shaped certain institutions: norms and rules for behaving within a rigid system of restricted freedom. When released, the former prisoners moved to special settlements without the right to leave for a specified period. Subsequently, the concepts and norms of prison culture were passed on to those who interacted with the ex-prisoners in any way. The stigmatisation of ex-prisoners, based on prison norms, spilt over to the outside world, including the stigma of homosexuality, which entrenched terms such as “top-bottom,” “punk,” “turned out” and so on. The criminalisation of homosexuality meant that former prisoners carried the stigma of homosexuality with them, in addition to memories of forced labour and abuse.

In the USSR under Stalin, people lived in constant fear of saying or doing the wrong thing – and ending up in prison. Over the years of the Gulag’s operation, more than 11 million people passed through the camps, which resulted in a widespread occurrence of prison culture.

It can be assumed that since the criminalisation of same-sex relations in Russia – that is, since its Europeanisation by Peter the Great – the gay culture has been marginalised, closed off, forbidden, and practised either in secret or in spaces that allow it. According to researcher Dan Healey, Russian prisons were already practising such relationships before the creation of the Soviet Union and were effectively a form of accepted systemic violence normalised by a particular prison code.

Given that the prison system in Central Asia emerged with Russian colonisation and flourished during the Soviet era, it is safe to assume that homophobia – in its current vile, horrific form – spread across the steppe with it.

Racism and homophobia in Central Asia

Today, our society continues to stigmatise people with non-heteronormative sexual preferences. We have already explored the roots of this aggressive homophobia in the prison system and culture of the Stalin era. However, racism is another important factor that overlaps with homophobia.

When we talk about the Gulags, we are referring to the entire Soviet Union, not just Russia. And while many books have addressed LGBT+ and homophobia in the context of Russia and the Russian Empire, very little research mentions the roots of homophobia in Central Asia.

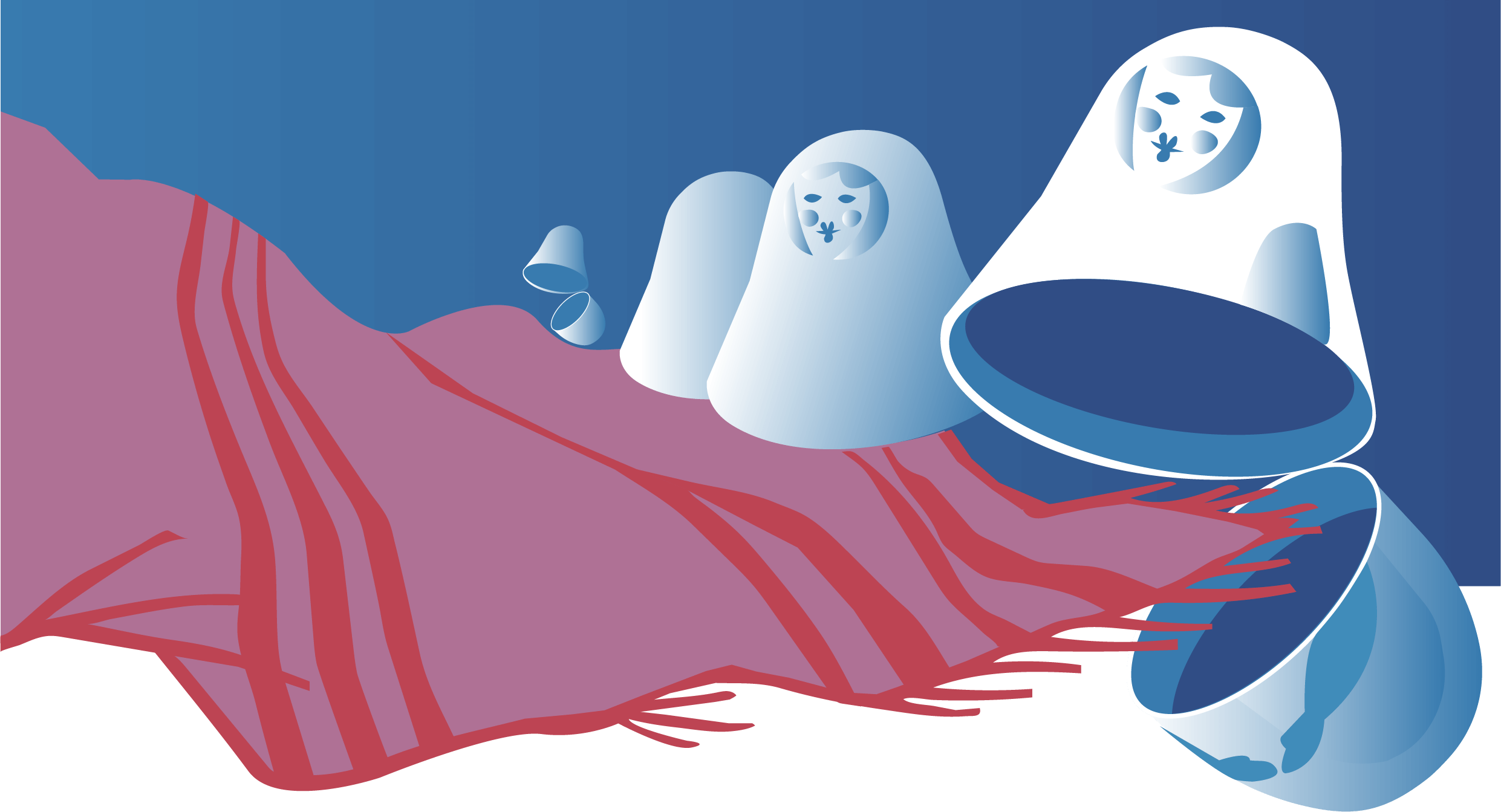

The Central Asian countries are heirs to the USSR in law-making and homophobic rhetoric. However, homophobia in Central Asia did not emerge in the Soviet era, but much earlier – with the onset of Russian colonisation and the research of ethnographers, military officers and travellers who created an image of the Orient for the Russian Empire. According to researcher Madina Tlostanova, 19th-century Orientalism involved the perception of the Orient and its peoples as objects of study – compelling and profoundly different from the European subject. Naturally, European travellers perceived any practice alien to their culture with surprise or condemnation.

An Orientalist interpretation of homosexuality, especially in its male variant, was common. Same-sex relations were outlawed, first by the Russian and then by the Soviet Empire – and presented as an expression of Central Asia’s pervasive morality, though unrelated to Islam.

The notes of travellers and ethnographers are full of condemnation of the Bacha culture – boys from poor families who were trained as dancers to please adult men. Such practices were of interest to travellers, described vividly and in detail, but seen as immoral and criminal.

Of course, nothing can justify the sexual corruption of young boys for the pleasure of rich men. But practices such as Bacha Bazi indicate the normalisation of homosexual life in general in the urban culture of Central Asia.

In the eyes of the traveller, the Orient presents itself as a colourful urban culture, full of men entertained by a performance of Bacha dancers – and women almost absent from public spaces.

Conclusion

It should be noted that negative attitudes towards gay people were particularly manifest during the Soviet era, due to the prison culture that spread throughout the country during Stalin’s rule. However, this is not the only reason for the stigmatisation of homosexuality: the colonial experience of Central Asia and the objectified image created by ethnographers and travellers are superimposed.

When we talk about the colonial roots of homophobia, we see that in the Russian Empire itself, before the reign of Peter the Great, homosexuality was treated as a gaiety. His attempts to Europeanise Russia led to a ban on various cultural and social practices, including homosexuality.

Peter the Great also laid down these rules in Russia, relying on European laws, where same-sex relations were punishable by death. Subsequently, these laws were only tightened, and even after the October Revolution, which initially decriminalised homosexuality, these persecutions were intensified.

It is worth bearing in mind that gay people, forced to conceal their identity, hid and found special places to meet and date. In Russia, these were public baths, toilets or flats. One such place was the prison – with its established culture of communication, its hierarchy and its institutions of punishment and subordination. Fear of Stalin and the desire for economic gain drove literally half the country into the camps, where the pre-existing prison culture included a dismissive and demeaning attitude towards gay people, and used homosexuality to create mechanisms of humiliation and oppression.

As far as the pre-Soviet era is concerned, we know little about homophobia in Central Asia – and a tendency to idealise the pre-colonial past is not helpful in research. It is possible that same-sex relations were condemned but not severely punished. This is something that needs to be explored in each and every region of Central Asia.

However, the image of the “effeminate Oriental man” constructed by Russian travellers, the condemnation of the practices of young boys and boy dancers, and the almost total absence of women in the public sphere influenced the disdain for homosexuality among those colonised peoples who had Bacha-Bazi-type cultural practices. All the more so because these populations were considered to be prone to “sodomy”, which made them doubly stigmatised.

References

- Vlad Skrabnevsky. Sudba gomoseksualov v Rossii: ot drevnerusskoy zabavy do ugolovnogo prestuplenia [The fate of homosexuality in Russia: from an ancient Russian pastime to a criminal offence]

- Daniil Melentiev. Etnografia i erotika v Russkom Turkestane [Ethnography and erotica in Russian Turkestan] // Gosudarstvo, religia, tserkov v Rossii i zarubezhom 2020, No. 38(2).

- Dan Healey. Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Dan Healey. Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi. Bloomsbury, 2018.

- Georgi Mamedov. Illuzia sovetskogo: konservativny povorot v Kyrgyzstane. Zakonoprojekt o zaprete “gey-propagandy” i sovetsky diskurs o gomoseksualnosti [The illusion of Sovietism: the conservative turn in Kyrgyzstan. The draft law banning “gay propaganda” and the Soviet discourse on homosexuality]. Kvir-kommunizm eto etika [Queer Communism is Ethics]. Svobodnoe marksistskoe izdatelstvo “Novye krasnye”, 2016.

- Georgi Mamedov, Nina Bagdasanova. Tema, a ne “LGBT”? Vremia I prostranstvo seksualno-gendernogo dissidentstva v postsovetskom Kyrgyzstane [Tema, or “LGBT”? Time and space of sexual and gender dissent in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan]. Cahier du Monde russe 62/2-3, Avril-Septembre 2021.

- Madina Tlostanova. Dekolonialnye gendernye epistemologii [Decolonial Gender Epistemologies].

- Rustam Aleksander. Zhizn gomoseksualov v Sovetskom Soyuze [Life of Homosexuals in the Soviet Union]. Moscow, Individuum, 2023.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Russian Propaganda’s Influence on Soviet and Post-Soviet Homophobic Narratives in South Caucasus

Russian Colonialism and Homophobia in Moldova

Migration Is the Path to Freedom. A Photo Report about Sumaya

Russia’s Homophobic Law Inspires Azerbaijani Political Elites

“I Put a Lid On My Sexual Orientation, I Buried It”: Life of LGBTQ+ People in the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine

Non-traditional Values: Did Uzbekistan Inherit Homophobia and Family Concepts from Soviet Union?

Gay Pride Parade, “Dazhynki” or White March: which holiday suits “Belarusians of the future”?

Beyond Blurred Existence