Beyond Blurred Existence

“I am Georgian and therefore I am European”, former Chairman of Parliament, Zurab Zhvania, said in front of the Parliamentary Assembly of Council of Europe in 1999.

[playht_player width=”100%” height=”90px” voice=”en-US-ElizabethNeural”]

Years pass and this quote continues to mark a loud call for Georgia’s European Union (EU) aspiration. Stuck between the Soviet past and the widely chosen European future recognized by the Constitution, Georgia tries to figure its self-identity out. While on a national scale, the present is overshadowed, some marginalised queer people try to grasp their blurred belonging to the society that refuses to see them, here and now.

“We are all rooted to one fungus base, whose task is to destroy the accepted social construct that seems to be standing firm, but actually rots from the inside.”

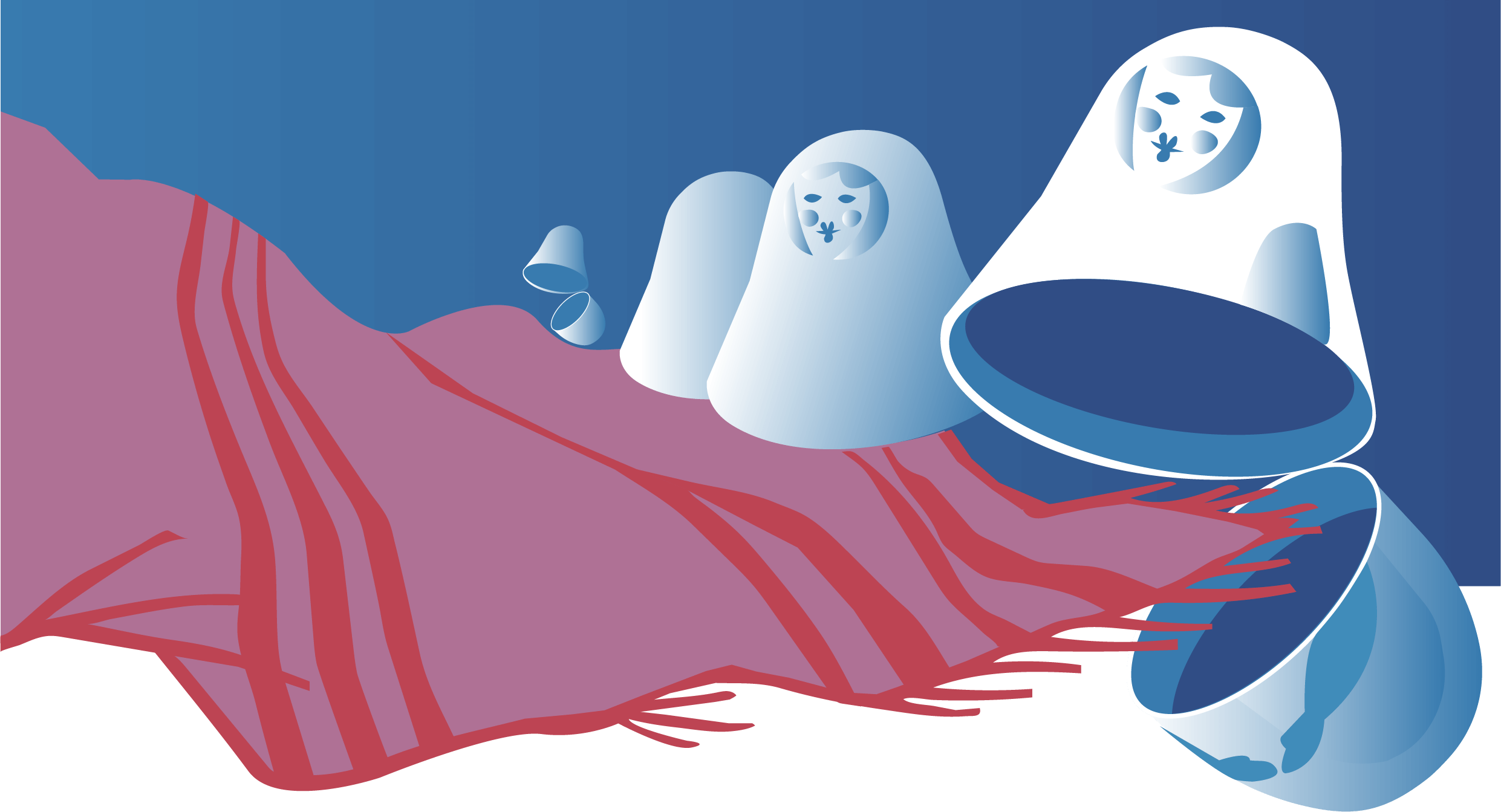

Based in Tbilisi, Georgia, queer art collective Fungus is an alternative space that attempts to deconstruct dominant structures and binary ways of being.

Founded by Uta Bekaia, along with David Apakidze, Mariko Chanturia, K.O.I. and Levan Mindiashvili, a multimedia artist based in New York and Tbilisi, Fungus is a collective movement for not only visual artists but writers, musicians and anyone who wants to express themselves and experiment. Finding a voice in Georgian tradition, culture and modernity, this movement is an example of visualising the coexistence of past and future grounded in the present.

“I want the freedom to carve and chisel my own face… to fashion my own gods out of my entrails…”

It’s this thing that Gloria Anzaldúa, an American Chicana lesbian scholar of working-class origins, tried to create through her writing, that I, as a queer woman from Georgia, attempt to explore through (re)thinking and (re)writing stories beyond a blurred existence.

Conversations about decolonising post-Soviet spaces are relatively recent. Coloniality and decoloniality may feel distant because of the geographical roots in another part of the world. Decolonial studies emerged in the early 2000s, largely made up of male scholars from Latin and South America, who have been working for the United States and European universities and research centres. Perception of the history of the Russian Empire as colonial in nature tends to be controversial. However, an adaptation of decolonial narratives may serve post-socialist nations such as Georgia to move towards self-determination, envisioning a more inclusive and equal society.

Thanks to history, nationalism and geopolitics, Georgia has not had the luxury of freedom to make sense of its identity. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the homogenous perception of the nation and nationals as Georgians became a key aspect of a dominant narrative negotiating the Soviet past and the European future. This resulted in exclusionary policies and the vision of minority groups as ‘others’, not fitting in the primary account of who may be perceived as Georgian. The marginalisation of queer individuals is no exception and continues to exist in narratives of ‘othering’.

How Uta navigates his ‘othering’ experience is through self-exploratory artistic practices. He engages with his sociocultural roots, his existence in the present and his expectations for the future. “It feels like socially accepted norms and rules do not apply to me. I am already perceived as an outsider because of my gender identity.” How he works his way around this is by allowing self-expression without any limitations or societal frameworks.

Paradoxical or not, the experiences of Georgian queer individuals and Georgia as a country are closely connected. Elisabed, a queer community member, believe that the (re)exploration of Georgia’s national identity is related to their self-exploration as queer. They think:

“In both cases, a rethinking of our experiences should not be about (re)building an identity, but it should be used as a method to deconstruct identity politics as such which imposes gender and sexual binary ways of being on us.”

For instance, they recall the experiences of their queer friends who often object to the perception of themselves or each other as either feminine or masculine. Elisabed believe: “Complexity of our identity is lost in this binary understanding. How I try to create safe space around me is, together with my queer friends, through practices of care.”

In this regard, Uta likewise believes the path of queer community members to self-determination is mirrored on a national level. He considers that Georgia is characterised by European pragmatism and Asian poetism. He shares: “I find one of the biggest challenges of Georgia is an identity crisis, influenced by the Soviet past and white colonial vision of the world. We, queer individuals, also face an identity crisis because of this, a perception of the self as not being worthy of owning our individuality.”

Uta connects this experience to the forgotten (queer) past. He adds: “We do not know where our queer identity comes from. There are only bits and pieces we try to grasp, such as Kinto from 19th century Tbilisi.” Kinto is associated with men, who were assumed to be queer. A marginalised group, they often dressed in traditional costumes and worked as entertainers at restaurants and parties.

Levan*, another queer community member, acknowledges the equally important connection between national identity and religion. Wider Georgian society equates Georgian identity with being an Orthodox Christian and embracing the values of the Georgian Orthodox Church. He argues: “Considering that the Georgian Orthodox Church often incentivises violence against queer individuals, religion in Georgia fuels our marginalisation.”

Returning to Georgia’s European aspiration, Levan’s conscious memories of Georgia’s transitional period determined by the European path stem from the Rose Revolution in 2003. Born after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he believes that following the revolution, LGBTIQ+ individuals and their experiences started gaining attention.

“If this had been a taboo topic, my self-perception as queer would be either very low or non-existent,” he said.

One of the ways to disrupt the long-standing patterns of coloniality and imperialism in a post-Soviet space is through decolonial practices of knowledge and being, unlearning what has been externally imposed and creating a conscious narrative; a story that reconnects with multicultural and inclusive roots of Georgia.

Referring to the word ‘queer’ is already an attempt to reclaim spaces queer individuals have been left out from. ‘Queer’ passes national borders and unites LGBTIQ+ individuals in an umbrella term, irrespective of where they come from. This is a vivid example of a decolonial practice, originating from the awareness of multiple identities that allows (re)connection with sociocultural roots and traditions, beyond and in-between dominant colonial narratives.

What this means for Georgia and the Georgian queer community is a journey that continues.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

What if homophobia in Central Asia is a product of colonialism?

Russian Propaganda’s Influence on Soviet and Post-Soviet Homophobic Narratives in South Caucasus

Russian Colonialism and Homophobia in Moldova

Migration Is the Path to Freedom. A Photo Report about Sumaya

Russia’s Homophobic Law Inspires Azerbaijani Political Elites

“I Put a Lid On My Sexual Orientation, I Buried It”: Life of LGBTQ+ People in the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine

Non-traditional Values: Did Uzbekistan Inherit Homophobia and Family Concepts from Soviet Union?

Gay Pride Parade, “Dazhynki” or White March: which holiday suits “Belarusians of the future”?