“This Is My Feminist Manifesto”

Violetta Tarasenko is an activist and openly gay woman. She has been fighting Russian propaganda with journalism and videos for nine years, and now serves in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. This text is an abbreviated but frank biography of Violetta, from the moment she became interested in human rights to the realisation that she is now forced to defend them with arms.

I come from a small town in self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic”, Avdiivka, where I lived for twenty years. I had a happy life and didn’t think about moving to another place, because Avdiivka was a small, cosy city where everything was calm and quiet. If we needed some action, we went to Donetsk.

I came out when I was in middle school, and later at work and to my mom. I have hardly ever encountered homophobia, which comes as a surprise to everyone. I dated girls from secondary school, gave them presents, and talked openly about my partners. Even in the company of so-called ‘bydlany’, they just spoke to me about it, and nobody acted aggressively, as I was also part of that group.

After high school, I entered the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Donetsk. At that time, I was not an activist and took no interest in politics, urban development, or legislation. During my second year of study, I completed an internship at the sole independent media outlet in Donetsk. This experience sparked my interest in activism.

Courtesy: Violetta Tarasenko

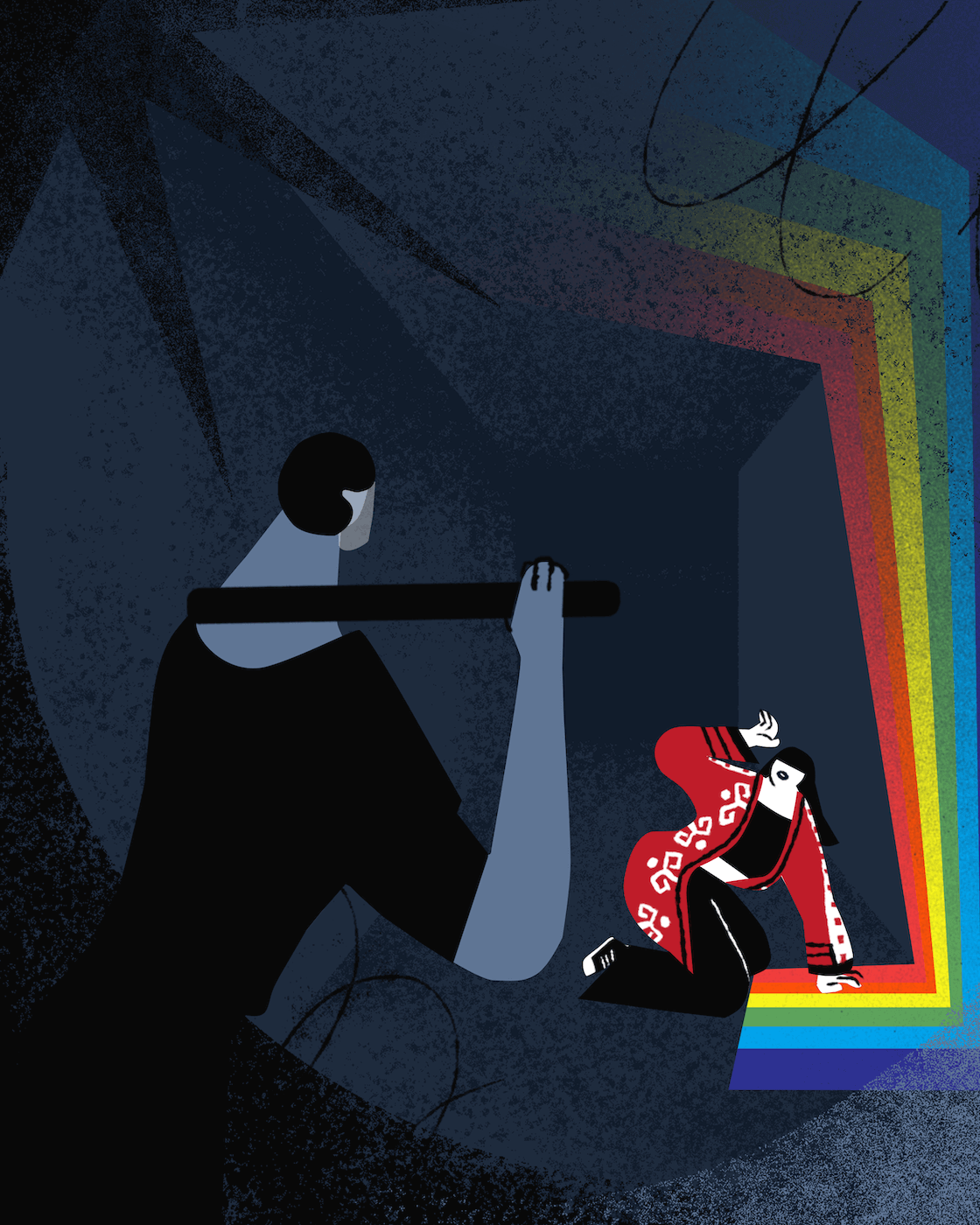

Soon after that, when the occupation began in 2014, I began to expose Russian propaganda through my journalism. I covered Donetsk’s Euromaidan rallies, attended by 150 people on better days. They were opposed by 200 ‘titushky’. They threw paint at us, followed people after the protests, and beat us in the stairwells. The police did nothing about it, did not stop them. I was at the rally when Dmytro Chernyavskiy was stabbed to death.

I saw everything with my own eyes. I witnessed the city getting taken over, with all that had been constructed during decades of independence being demolished. For the past nine years, I have carried this pain. Therefore, I have worked to oppose Russia and the conservative values it promotes, specifically within Ukrainian society. For instance, the conservative ideas of extreme nationalism seem identical to those of Russia but expressed in Ukrainian.

I also went to all the pro-Russian rallies, covered them live, and showed what was really happening there. Due to this, my private information and photographs were shared across pro-Russian social media groups, which identified my location and made the call to locate and harm me.

Over time, I left Donetsk and returned to my native (then occupied) Avdiivka. At the time, the occupation authorities were actively searching for me. They referred to me as a spotter because I identified the locations of checkpoints, the people responsible for them, their funding, and other details.

Once, I was trying to take my grandmother to a secure location when a van arrived at the bus stop and two individuals with firearms disembarked and attempted to coerce me into going with them. I replied that I was not going anywhere because I had an old lady here who needed to be taken to the train. Then one of them made several shots in front of my face, trying to intimidate me. But my face did not move. It was the first time I realised that I don’t panic in stressful situations. I stayed put and persisted that I had to send off my grandmother first before I joined them wherever they wanted to go. And they just left! I think what helped me was that there were a lot of people at the bus stop, and I’m a one-and-a-half-meter-tall girl. They just couldn’t push me into the car in front of everyone.

Courtesy: Violetta Tarasenko

“After the liberation of Avdiivka, I moved to Kyiv. You could say that my beloved city was dead. Cut off from Donetsk which is still occupied, Avdiivka didn’t develop much. There was only work available at the factory and most of my friends left. It was just a border point between Ukraine and the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic” that was being gradually destroyed by Russian artillery.

In Kyiv, I kept up with my activism, but things were different than in Donetsk where we only protested Russia. I started going to rallies for women’s and queer rights. It is interesting that in Donetsk, separatists tried to intimidate me, but in Kyiv, they were replaced by right-wing radicals. But after being threatened with an assault rifle, the attacks of teenage radicals only made me smile.

I also did not stop working as a journalist, and overall, I dedicated nine years of my life to opposing Russian propaganda. Also, I worked for Update, a website that discusses human rights, mental well-being, and drug regulations, which is renowned among the LGBT community.

But Kyiv did not become my home. In 2019, I decided to move to Mariupol because I really wanted to go back home to the Donetsk People’s Republic. I spent three happy years there and I loved my life in Mariupol. It was a really calm European city by the sea. Every two months new venues opened there. There was a continuous effort to fix and renew the space. We saw that money was really being invested in the city.

We also had our own space, the TU platform. It was a place for LGBTQ+ individuals and anyone who felt uneasy in their homes, workplaces, or town in general. It was a place for lectures, parties, film screenings, workshops, and a wide variety of art.

Several times we were attacked by local right-wing radicals, who smashed everything and hit the staff. But later, the police interfered and the attacks stopped. Over time, the whole city knew that there was a platform called TU, that gays were ‘hanging out there’ and holding their ‘gay parades’ every year. In fact, we organised events about human rights on different issues. In the last year of the platform’s existence, we had a fantastic programme for teenagers, which drew in plenty of enthusiastic young people.

This art space was created by IDPs from Donetsk, and I think it was the experience of struggle that made us more active. We wanted to do something for society, not just sit around. We liked living in Mariupol.

Courtesy: Violetta Tarasenko

On 24 February 2022, my partner and I woke up at 6 a.m. to a call from a friend who asked if we had heard explosions in Mariupol. I went online and saw on Telegram news channels that a full-scale war had started. We woke up calmly, I was preparing our breakfast, while my partner contacted her friends abroad. I knew what to prepare for, so I didn’t panic, I had already packed my things and my ‘survival kit’.

There is probably no point in talking about the occupation of Mariupol. Everyone already knows what happened there. Heating, water, gas, and other utilities were shut down almost immediately. So were the Internet and mobile communications. No one counted the dead there. People were buried in their yards, there were cemeteries in every park, and people burned in their own homes. No one will ever find them.

It was also difficult because I was at my partner’s house, with her family. Because there was a military unit in my yard. there was a military unit in my yard. Her family didn’t like me very much, so I had a feeling that I was out of place and I had nowhere to go. We were under occupation until March 17, and then miraculously managed to leave.

When we got out of Mariupol, we broke up. I think I couldn’t cope with the stress and she saw our life differently and decided not to continue the relationship. While we were there, I didn’t feel supported, and that’s probably why I couldn’t be a support for someone else.

From Mariupol, I went to Zaporizhzhia, then to Kyiv, then to Lviv, then across the border to Greece, where my mother has lived for many years, and then I stayed with friends in Georgia for a few months, and finally, I ended up in Berlin for the first time. But I decided to return to Ukraine. I don’t want to flee, I don’t want to live another life abroad and be displaced again. Again! Ten more times. I have the strength to fight them.

At the end of last summer, I started preparing for the army. I did some training with my neighbour, borrowed body armour from my friends, and wore it for a few hours every day to become accustomed to it.

I was accumulating anger at Russia and at what happened in my relationship. For the whole year before I joined the Armed Forces, these emotions fueled me, I had no other life. Apparently, I did not fully process what happened to me with a therapist, neither in terms of what I experienced in Mariupol, nor in terms of breaking up with my girlfriend, nor in terms of the fact that my hometowns were destroyed. The rage just kept accumulating inside me and I decided that I was ready to go to war.

I cannot say that I am not afraid to die for Ukraine, because I want to live for Ukraine. But I can’t imagine any other life now, where I would be in a safer place, for example, in Kyiv, working a civilian job, going on dates and parties. I tried to do all that when I came back to Ukraine, but I realised that I couldn’t because my mind was always on the war.

When people asked me why I was joining the Ukrainian Armed Forces, I answered, “Who else but me?” Because I saw Kyiv living a peaceful life again, with parties and recreation. I saw robust men come up with the excuse that they were holding the economic front by donating. We do need donations, without them we would be fighting with our bare hands, but without people, there would be no army and no one to donate to. The war became something far away again when the Russians withdrew from the Kyiv and Chernihiv Oblasts. We are running low on willing men to fight, and sometimes the ones who are called up do not behave honourably. They drink, leave their post without permission, and desert their positions.

At the same time, many of my friends tried to dissuade me and did not believe in me because I was a woman, because I was one-and-a-half-metre-tall and weighed fifty kilos. Even if women join the army, commanders are hesitant to assign them to combat roles or send them on combat missions. I don’t want stereotypes to stop me, I’ve been fighting them all my life and will continue to do so, just now I will do it in the Armed Forces.

Courtesy: Violetta Tarasenko

To officially register in the Armed Forces, I went to the Military Commissariat for two months — they refused to enlist me by contract. They were looking for different reasons to refuse, I had to provide a lot of documents. At first, they wanted to mobilise me as a combat medic. I said that if I became a medic, it would be of my own free will, not because they wanted to make me a medic because I was a woman. Only after that, I was offered a three-year contract.

After signing the contract, I was finally sent to training. It felt like a prison. They don’t train or prepare for war, but rather for a military-style service like in the Soviet Union. All we did was dig trenches and carry things back and forth, and we had no right to talk back to our superiors. The chief instructor kept repeating during the training that he did not really believe in women in the army and was suspicious of the fact that there were now so many of us. That’s all the training we had.

Now I have arrived at my unit. I serve in the Ivan Bohun First Separate Special Forces Brigade, part of the Dyke Pole (Wild Fields) battalion, in an assault company. Our battalion holds positions in the Lyman sector on the border of Donetsk and Luhansk regions. I’m a soldier of this battalion, I’m not allowed to say more. I cannot say that I am in my proper place, because I don’t think anyone belongs in war. But for sure I feel better here.

Of course, everyone tries to take care of me, I’m the only woman here, but other than that, I’m treated like everyone else. The only thing is that I get to be treated with candy more often. In fact, everyone here is polite and nice, and everyone is just doing their job. But there was one case where, on my first night on duty, I was told by a fellow soldier that I should be “producing children instead of sitting there, that there was no need for a ‘skirt’ in the position”.

I didn’t tell anyone about my orientation, but one of my brothers-in-arms, with whom we share all our meals, found me on Twitter. I post there about queer feminism and all that. I was very embarrassed, but he turned out to be an okay person, and he even started following me. I mean, not everyone here is homophobic, he didn’t stop communicating with me because he saw what I shared on Twitter.

There was another story. One guy liked me and asked me for my Instagram. Then one night he came and invited me for tea, and asked if I was gay. I admitted honestly. It is not something I tell everyone, but neither will I be a liar and a denier. It was my first coming out here and I was very nervous waiting for his response. His first words were, “The guys will be shocked,” and I said, “Yes, they will.” I couldn’t sleep all night and didn’t understand what would happen tomorrow. If he told anyone, the whole company would talk about it. But he turned out to be decent, and we still hang out, train together and are friends with each other.

Courtesy: Violetta Tarasenko

The key message for everyone to understand is that it’s not the Nazis aiming to seek retaliation against the Russians, as some assume abroad, but rather regular Ukrainians who are tired of being targets. I want to take revenge for everything the Russians did to our country, to its people, for all the broken lives of my friends and my own.

For nine years, my friends and I have been dreaming of going back to Donetsk and strolling on the Kalmius riverbank. Now this feeling has become very real and it keeps me going. The main thing is to stay alive and prevent our country from becoming a military dictatorship or becoming conservative after winning.

That is why I need to show that LGBTQ people are just like everyone else, like other Ukrainians who are ready to lay down their lives. That women are ready to lay down their lives, that this is not only a man’s business, but everyone’s business. This is my feminist manifesto. I am here to defend the values of freedom and equal rights for all. Maybe others are fighting for something else, but I am here for this.

Edited by Inga Daraselia

Translated by Valeria Khotsina

The original article was published here (in Ukrainian)

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect