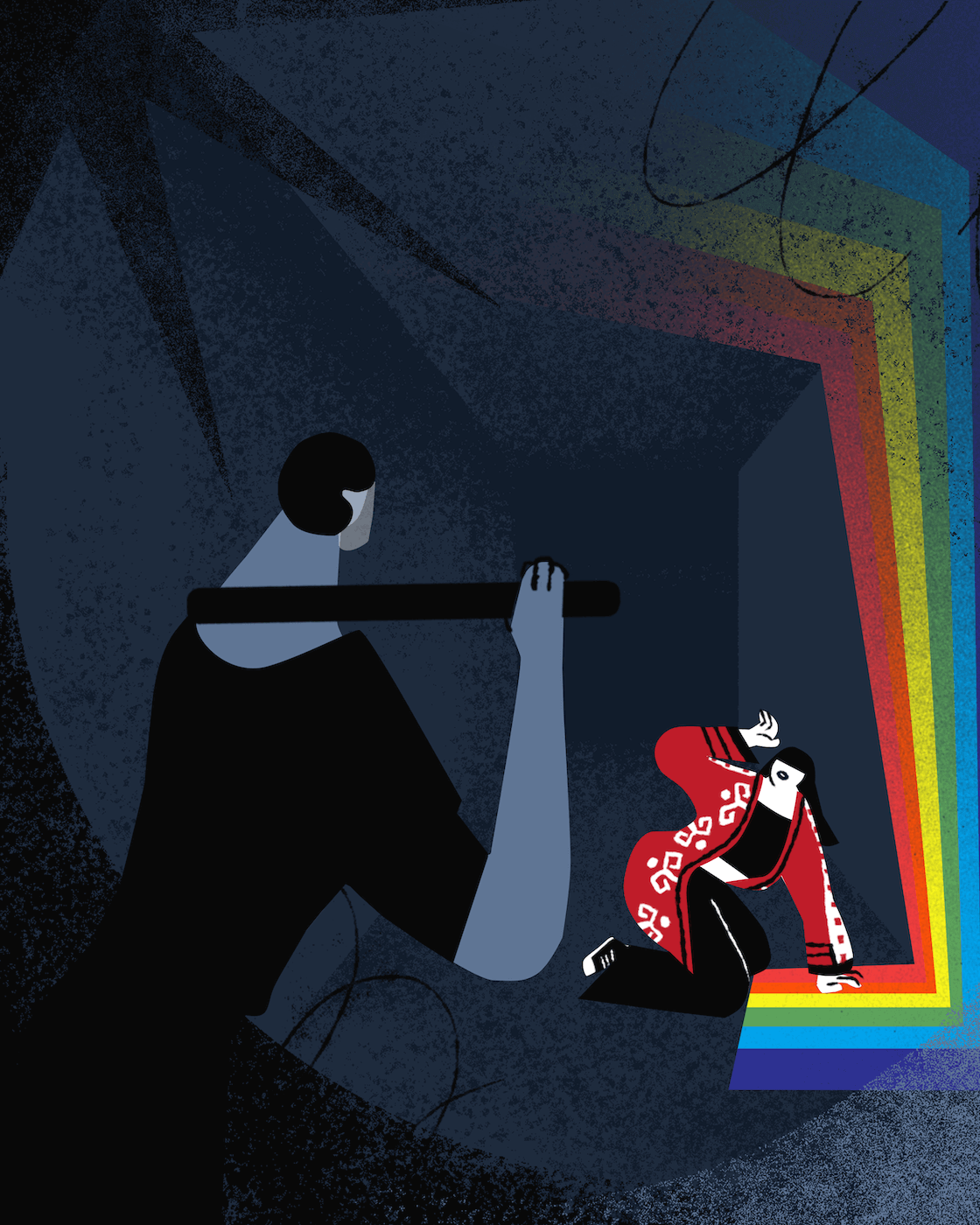

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

Even though there is no legal prohibition on writing about LGBT rights in Uzbekistan, they are not discussed in the media articles. Instead, criminal articles are used against those who support these rights. They are being held in jails and prisons under Article 120 of the Uzbek Criminal Code which is considered to be violating human rights. Until recently, no one knew about the conditions of their detention or details of investigating such “crimes”.

sarpa recorded the experiences of three young individuals who were imprisoned for 1 to 2.5 years under Article 120, served their time in prison and correctional facilities, and shared their stories of blackmail, extortion, torture, violence, and life after release, even though it sometimes feels like mentally they are still in prison.

Names have been altered.

“I had a good job and managed multiple companies. Now I have to save every penny of my salary of 1 million sums (~$100) as 15 per cent of it is taken by the government. Nobody wants to hire individuals who have been in prison, especially under this article,” Amir said.

He used to work as a production director one and a half years ago but currently holds a watchman position at a warehouse. Unlike other young people his age who are advancing in their careers, he had to bear 2.5 years of imprisonment under Article 120 of the Criminal Code. This experience has had adverse effects on his health and left him with many stories, which, as he says, can fill a whole book. He also was blackballed in many ways.

The acronym “LGBT” has turned into a bogeyman in Uzbek society. This is incompatible with national values. Obviously came from the West. “Perverted.” Spoiling children. Spreading propaganda! False ideas about members of the community are especially prevalent online on the eve of significant political occasions. At the same time, actual individuals from the LGBTIQ+ community in the country live in the most subdued way feasible due to the danger of being criminally charged, and the overall disapproving nature of the conservative society.

This state of affairs prevents the slightest information about LGBTIQ+ rights in the country from leaking into the media. Just a year ago, the first-ever published data showed that 36 people were found guilty under Article 120 in 2021. Earlier, the precise count of criminal cases stayed undisclosed — officials declined to give this data to reporters.

What happens to those who were sentenced under this article and served their time in Uzbekistan’s prison system? Do the problems end there or is this the start of more stigmatisation?

Vocabulary

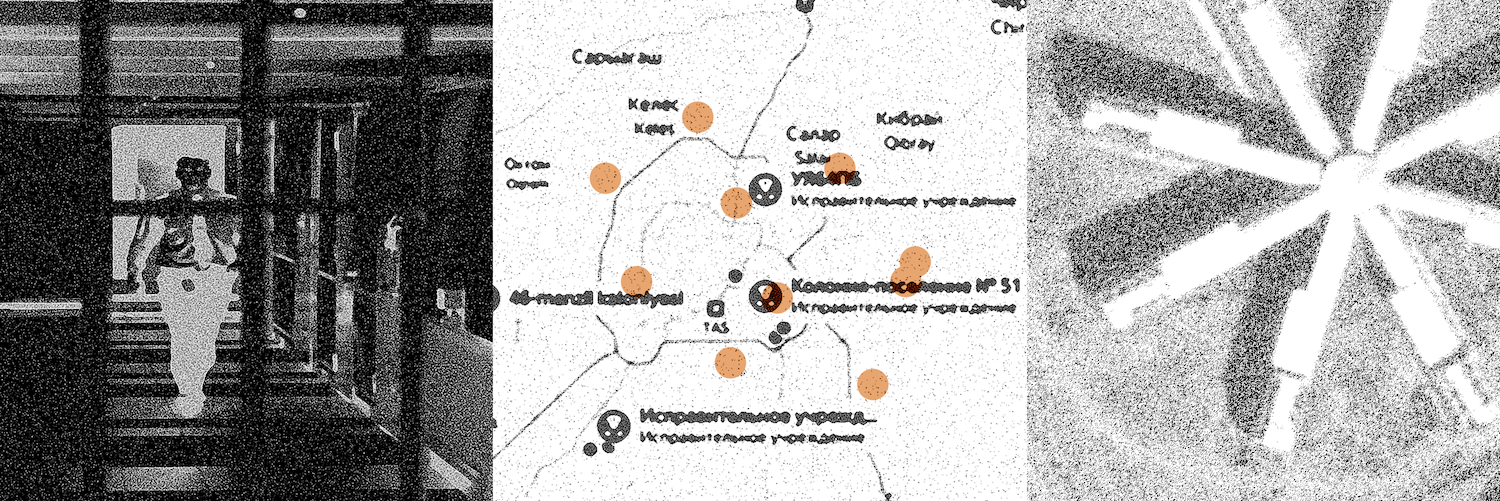

Remand centre — a place where defendants on trial and convicts are held while awaiting transfer to correctional facilities or penal settlements. Remand Centre No. 1, also known as Tashkent Prison, is mentioned in the text. People can spend several months here, waiting for their court decision or a transfer.

TDF — temporary detention facility. People suspected of committing crimes are kept here. They can be held there for a maximum of 10 days.

CIAD — Central Internal Affairs Directorate

Article 120 of the Uzbek Criminal Code (“sodomy”) criminalises consensual sexual activity between two adult men and carries a penalty of up to 3 years in prison.

Article 113 of the Uzbek Criminal Code criminalises the transmission of venereal disease and HIV/AIDS.

Count refers to a single occurrence of the crime. For example, under Article 120, one “count” could be one alleged instance of consensual sexual activity between two adult men.

Penal settlement is the least severe type of correctional institution. Inmates are allowed to wear regular clothes and move around freely. They can even work and use money.

“Muzhiki“ (rus. labourers) is the biggest group of prisoners and is less powerful than the “blatnye” (rus. crime lords). However, they are also respected.

“Downcasts”, “turned out” are prisoners who are declared to be members of a lower caste in the prison hierarchy. It is generally believed that “downcasts” are prisoners who engage in homosexual activity in a passive role, whether willingly or forcefully.

Amir

Received a two-and-a-half-year sentence in a penal settlement under Article 120 of the Criminal Code in Uzbekistan. Was held in Remand Centre No. 1 for most of his imprisonment and continued serving his sentence in Penal Settlement No. 49.

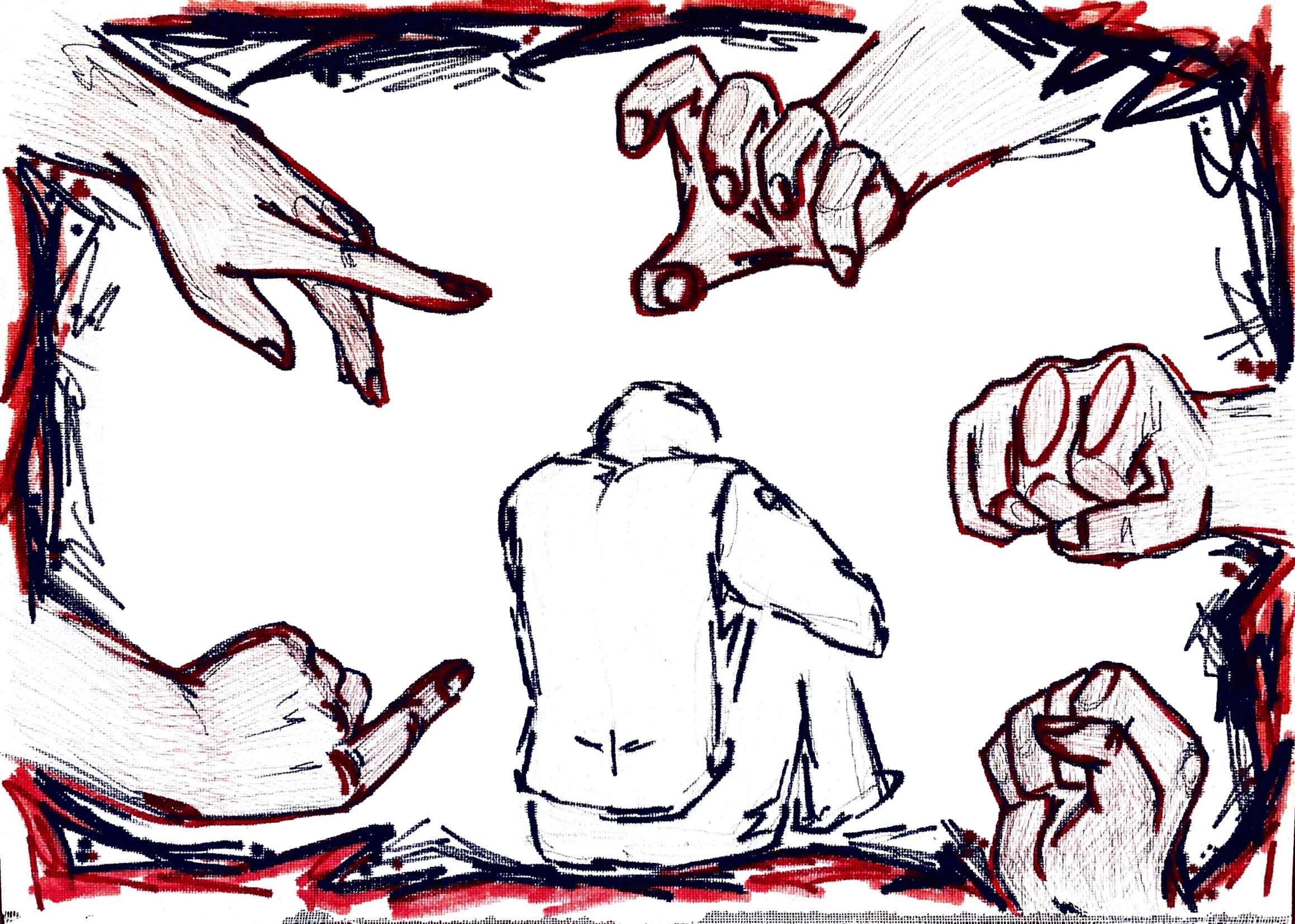

On 7 April 2021, men in plain clothes arrived at Amir’s house. “I thought they were going to kill us,” he says. He remembers how they put him on the ground in the corridor and handcuffed him, while his friend was beaten in the kitchen. The people who entered said they were from the AIDS department of the Central Internal Affairs Directorate (CIAD).

As the young man remembers, at first the officers tried to “negotiate”. Later, according to him, they changed their mind and took everything from the flat without negotiation or payment. Amir provides a list of items that were taken: a laptop, Apple Watch, golden items, cash, headphones, iQOS electronic cigarette, and even a charger. The flat wasn’t sealed, and there was no witness or video recording.

Plain-clothed police called a taxi using Amir’s phone to the Ministry of Interior’s headquarters and told him to only take his passport and phone. “They grabbed the laptop and asked me if it was borrowed or bought. They said I would not need it for a while.” The young man also showed us screenshots of payment applications: within a month of his arrest, they had transferred all the money from his bank cards to other cards, sent 59,000 sums (~$5) in cash backs from the Soliq application to his card, and linked his Google account to a different number. There have also been applications to the Tax Commission on his behalf, two attempts to take out a loan from one of the online banks and regular attempts to access his Instagram account from other devices.

sarpa has all the screenshots at its disposal.

In the Mirzo-Ulugbek police department, the young men were put into a cell. On the way their wallets got confiscated: the officers said they took them “for the time spent on processing the detainees, petrol and not having time to eat because of them”. There, Amir and his friend Kamil were assigned an investigator and a lawyer. According to them, the latter stopped paying attention to them when he found out what article they were charged under. Meanwhile, Amir’s parents started looking for him; he was not allowed to make a phone call or report his whereabouts. The detainees also say that they were deprived of food and medication that is needed to treat Amir’s chronic illness. Amir was kept in the holding cell of the police station for six days until his bruises disappeared: detainees have to be sent “clean” to the next reception point.

“Then they took us to the CIAD, and that was the most frightening place,” the young man recalls.

CIAD

Amir faced charges under multiple articles. He was accused of committing sodomy in three instances, indicating a violation of Article 120. Additionally, he faced two charges under Article 113, as he was found to be HIV-positive. He was also charged with causing someone to commit suicide, as the young man, whose testimony led to Amir’s investigation, killed himself after his first interrogation. “The young man was only 17 years old and had a very religious family. His father and brother physically assaulted him when they found out about his sexual orientation,” said Amir, who had only met the boy once. Even with such limited interaction, Amir was accused solely based on this individual’s testimony. Eventually, the suicide and HIV-related charges against Amir were dropped for lack of evidence. “Although his death was caused by the police and his father, they tried to shift the blame on me by accusing me under this article,” he explains.

As per Amir, lawyers refuse to take on such cases. Those who do charge a significant fee. Amir’s initial solicitor requested a lump sum of $1,000 and additionally charged 500,000 sums for each visit while he was in custody. Moreover, as per the ex-convict, law enforcement officials provide a simple method to get a charge dropped: collaborating and snitching on ten other individuals. But he thinks it’s not worth it because they’ll group you with each of these people later on for a separate charge. Amir remembers how he felt furious about the treatment he got at CIAD:

“They called us ‘faggots’ and yelled that we were spreading diseases.”

Thus, the young man was only charged with Article 120 for “sodomy”. He stressed that there was no proof of his sexual interaction with other men, and the prosecution relied solely on his and Kamil’s testimony obtained under duress and the so-called “forensic examination” done by a pathologist at Tashkent Medical Academy in the morgue building. This examination involves forcibly inspecting the anus, but it is difficult to determine sexual activity through such a method because physical evidence can result from the use of intimate toys or medical procedures.

During the last court session, Amir remembers the judge saying that in Uzbekistan, it’s acceptable to marry another woman under certain circumstances, as permitted by God, but this [homosexuality] is prohibited. The judge added that Amir would be luckier to be charged under Article 119 (rape). The trial lasted for eight sessions, but the defendants could not be present at three of them. Although the young men made statements during the trial about torture and robbery, the investigators were never summoned for questioning.

Ruslan

Sentenced to one year of imprisonment in a penal settlement under Article 120 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan. He spent six months in jail before being transferred to Penal Settlement No. 42 located in the Zangiota District.

Ruslan, who was 18 at that time, faced charges under Article 120 for engaging in “sodomy”. The charges were pressed against him after he got tested HIV-positive at the Republican AIDS Centre. Psychologists and epidemiologists used fictitious names and tricked Ruslan into confessing his sexual orientation. They then shared his personal information with the law enforcement agencies. Ruslan agreed to cooperate with the investigation and confess in exchange for freedom. However, he was deceived, as he received a one-year sentence in a penal settlement at the trial.

Read more on Ruslan’s story in Code 103, an article published by sarpa in 2022.

“I was shocked because the investigator had promised me a suspended sentence. I was planning to go home, when they said to me, ‘Where are you headed? You’re going to prison!’ I was handcuffed and taken to the remand centre. The courtroom and the temporary detention centre, where convicts are held after the trial, are two different dimensions.

“Upstairs everything is clean, beautiful and spotless, but downstairs, in the basement, it’s an actual nightmare — filled with sweat, smoke and prisoners shouting ‘Have you received a real prison sentence?!’

At the detention centre, they removed my shoelaces and my expensive belt, which was never returned. I was taken to the police department in a police wagon and put in a metal cage with just one seat in which all movement is restricted. I started to feel claustrophobic.”

Ruslan describes how he was taken to an investigator. The room at the CIAD was not fitted with surveillance cameras. Suspects are required to sign a paper stating that they have not been tortured before entering the room. It is written as directed by the officers. You must sign it, refusal is not an option.

Ruslan states that he was undressed and forced to stand on all fours in an office without cameras. His clothes, including his jeans and sneakers, were cut with a blade and thrown in his face before he was taken to his cell.

He claims that the holding cell at CIAD is quite clean. You are only allowed to sit on the edge of the bed. You cannot lie down on the bed between 6:00 and 22:00. The mattress should be rolled up during this time. If you break the rules, you will be sent to the basement. In the basement, they will have you learn the national anthem. If you cannot sing it all the way through, they will hit your heels with truncheons. But this is considered to be okay treatment.

Things are better now. Under Karimov’s rule, people were electrocuted in the basement.

Kamil

Sentenced to two years of imprisonment under Article 120 of the Criminal Code. He spent almost 7 months in Remand Centre No. 1 and some time in a penal settlement.

When Amir was pinned down in the hallway of his apartment, his friend Kamil was simultaneously beaten in the kitchen. “He had just had spinal surgery and had a scar on his back, and they intentionally attacked him and literally jumped on him. Then they became scared that they might kill him, so they tried to stop each other,” Amir explains.

Kamil and Amir were taken to the CIAD where they were grilled further. After that, the officers requested an ambulance. The doctors were not permitted to take the young men to the hospital. The police officers ordered the paramedic to carry out the “examination” on the street. All of this was recorded by surveillance cameras. According to the young people, their lawyer found the video recordings and presented them in court. However, the judge did not consider them as evidence of violence and torture.

Kamil grew up in an orphanage and lived with his sister. His friends believe that his challenging childhood impacted his mental well-being, and he took the incident particularly harshly. Following his arrest, he attempted to hang himself on his turtleneck in the cell. He found a blind spot on the CCTV camera and waited till the end of the roll call before attempting. He was saved on time, but later his file was marked as “suicidal”. Kamil still does not want to discuss his time in jail, even though he has been released for several months.

Meeting

Amir, Ruslan and Kamil met at Remand Centre No.1, commonly known as Tashkent Prison, which was relocated to a new building in 2018. The new facility is situated in the Zangiot District of Tashkent Region, an area filled with correctional facilities. This new prison is distinctive for its “camomile” shape — reportedly the only one of its kind among correctional facilities in post-Soviet countries, as stated by the builders. The cell blocks’ layout guarantees a uniform supply of light and air to the cells.

Ruslan remembers his first day in detention. “They shouted from the windows — Andijan, Samarkand!” Like it’s a railway station. They do blood tests, examine lungs and shave the heads of everyone in a mechanised manner. I never cried before, but at that moment, I did. They forcefully cut my hair with a trimmer similar to the one used for shearing sheep. They moved it over my head three times until there was no hair left. It was a humiliating experience.”

He was taken to a temporary cell where prisoners stay together until their test results are received and they can be assigned to other cells. There he faced his first conflict with other prisoners who were shocked to hear about his charge. “Jalyab [uzb. slut], either knock on the cell door now and ask the guards to get you out of here, or you are getting hurt.” The young man banged on the door from the inside and the guards took him out of the cell.

The guards were confused about where to take him next, saying “We have a gay here!” In prison, the staff treat you differently depending on your category and social status. Money is not a factor. This kind of corruption seems to have been eliminated, so one cannot buy better treatment. Ruslan’s charges were not the most prestigious, so he was given a rusty cup and a torn mattress.

After some thinking, the guards sent him to a cell where people like him were held.

Tashkent Prison has two cells where defendants with similar charges are held: 81/04 and 81/06. Ruslan was sent to one of these cells and met Amir there. “The door opened and he appeared — still small and with good teeth (teeth quickly decay in detention). He was standing there with a mattress and crying.” Amir remembers giving him bread, a stock cube and sweets.

Amir was held in the Tashkent Prison for several months. The trial had already taken place, after which the prisoner was to be transferred to a penal settlement where the conditions of detention are not so harsh. However, it took a long time for it to happen. In the end, he decided to start a hunger strike and, as he claims, “banged his head against the wall.” Eventually, it was successful, and he was moved to Penal Settlement No. 49. You can walk around here in casual clothes, have your family visit you, receive parcels, and use the phone. But according to the young men themselves, it is safer to be in solitary confinement for people with Article 120 — in a penal settlement they may face abuse for being gay.

Ruslan and Amir said that they became friends right away. Ruslan recalls that he realised he would not be alone there when he saw that a fellow inmate had tattoos and was dressed stylishly.

However, they had to hide their companionship because they feared being punished for knowing each other from the outside. They shared the cell with a transgender man who was convicted of fraud and waiting to be transferred to a correctional facility for some time. He is still serving his sentence.

When discussing their daily life in prison, Amir and Ruslan mentioned how “fortunate” they were to have a relatively new prison with a two-person cell for the three of them, as compared to the usual larger cells which house around 6-12 people. Ruslan had to sleep on the ground. Amir remembers that it was constantly cold, as the windows were removed from the frames in early April and only installed in October to let fresh air in.

The young men said that while physical violence was not used in the prison, there was psychological violence happening there. Basic necessities, such as toilet paper or medication that the young men had to take for their treatment, were not easily available. The family had to provide them with everything they needed. The boys said they were taken for a walk every week or two, but the walk only lasted for half an hour and took place inside a concrete box with no ceiling. Three of them had 15 minutes for showers, but only one stall was working and the water was predominantly cold. The prisoners could tell the time by looking at the movement of shadows in the cell, similar to a shadow clock, or by listening to the 102 FM radio, which the guards could switch off at any time.

The settlement staff gave Ruslan the female name “Rayhon” and only addressed him by that name. To maintain good relations, one had to behave respectfully with the guards. One example of appropriate behaviour was shining the staff’s shoes while they were smoking.

The young man said he was immediately told “how he should behave” because of his article. He could greet other inmates only by feet — by touching their shoes with his boot. Shaking hands was unacceptable. Cigarettes must only be offered in closed packets. Eating in the canteen was only allowed at the “clearance table”. At this table, newcomers are asked about their identity and their charges. Those who have committed murder are allowed to the common table. Ruslan remembers being asked if he had any boundaries or not at the clearance table. “Having boundaries” means that you only engage in oral sex with men. However, if you are open to other sexual practices, you are considered someone who doesn’t have boundaries.

Inmates also ask this out of personal interest. Ruslan says that even inmates convicted under different charges, who do not identify themselves as gay, harass gay men. Apart from attention and harassment, a convicted murderer even gave Ruslan gifts like flip-flops and cola. Ruslan could not refuse these gifts because of the existing hierarchy in the prison. Because he had been sexually assaulted in the bathhouse, the young man avoided bathing for an extended period. Ruslan remembers that rapists were strangely respected there. Particularly if they spend time with individuals who have committed multiple murders.

“In prisons, the most precious items are matches, naswar, cigarettes and lighters. Money holds no value,” the young men shared their experience in detention. To make life in prison bearable, inmates try to find ways to bring some comfort to their circumstances. Some of these methods include making cakes from biscuits and butter, saving sugar and brewing stewed tea — a strong drink made from black Tashkent tea that is known to have awareness-inducing and narcotic properties.

Prisoners are allowed to make a 10-minute phone call once a month. As this allocation is insufficient, prisoners resort to blackmail to obtain more time. Some former prisoners have reported extreme measures such as swallowing a spoon or cutting their veins to achieve this.

In prison, time goes by for inmates without understanding what is happening outside the facility. “They serve long terms, unaware of what’s happening outside. They’re not aware of the new bridge on Chilanzar, the Tashkent City development in Mahalle, or that the Malika fair is not being held on Alisher Navoi Street anymore. They’re not even aware of the metro line extending to Kuilyuk. In their world, time froze when the Samsung Galaxy S4 was released. They only get information through Zor-TV and the radio. On Saturdays, they watch movies,” Ruslan exclaimed.

Amir shared that they tried to have a good time, listened to the radio and chose to remain positive. Kamil, who was in the adjacent cell, was unable to accept the new situation.

Sangorod

Due to the harsh conditions in prisons and penitentiaries, many prisoners dream of getting to Sangorod, a facility that offers treatment services for dental and chronic illnesses.

Ruslan was sent to Sangorod when he fell severely ill. In Sangorod, the inmates are served grilled chicken and can watch TV every day. Sangorod is a desirable destination, as some inmates can relax there. However, the facility only admits inmates for a maximum of six months, and not everyone is eligible. The situation at Sangorod is distinct for younger prisoners who have been convicted under Article 120, though. Ruslan was given the most unpleasant job of washing the corpses of people who had end-stage HIV and died within the institution.

“When you are sick and have only a month or two left to live, the institution usually discharges you to die at home to keep their statistics looking good. However, some people are not discharged in time. One person, named Sasha, began to die and was moaning in pain all night. Unfortunately, the institution did not provide him with pain relief and only moved him to a different ward. The isolated room was located in the tuberculosis department, where patients with tuberculosis are monitored if they are unsure whether their disease is active or latent. Ruslan was tasked with watching over Sasha in the quarantine unit.

“I gave him food from a spoon, cleaned him up, changed his bed, and washed the orange cloth. He passed away during the night. He was examined only the following day, but by then he had swollen up and had a very bad smell.” Ruslan was instructed to flip the man’s body over to capture pictures from various angles. At that moment, Sasha’s lymph nodes ruptured, and black fluid gushed from his mouth and eyes, hitting the people around him. “That’s when I understood that if I remained here, a similar end was waiting for me as well. It was frightening.”

After prison

Ruslan left prison in October 2022 weighing only 45 kg and struggled to find a job for a while. He is currently on parole. Amir, on the other hand, is serving his sentence while on probation, which means he transfers 15 per cent of his earnings to the state.

He explains that it’s almost impossible to find a job after being in prison. Although the employment office offers some vacancies, employers tend to deny applicants with a criminal record under flimsy pretexts. The only work opportunities accessible are as a security guard that pays 1-2 million sums or as a worker at a waste disposal site with a salary of 800,000 sums per month. However, obtaining an official employment contract is essential, as, without one, you will be unable to make payments to the state.

Ruslan has shifted through multiple companies because every attempt to obtain a job was thwarted during the paperwork stage when his criminal record was discovered. “They cannot legally refuse to hire me due to my criminal record. Therefore, they resort to bullying me, making jokes, blaming me for any problems, openly discussing my failures, and eventually coercing me to resign on my own.”

While still in prison, Amir began writing petitions to the Prosecutor General’s Office hoping to get back his belongings that were stolen during the search. Subsequently, he received back his phone, empty wallet, and passport. The second appeal he made went unanswered.

Amir wrote to the Prosecutor General’s Office again, but this time through the “presidential portal”. Afterwards, he was informed of an ongoing investigation against the officer who had overseen the theft. Later on, Amir began receiving phone calls, and pressure was put on him. It turned out that the father of one of the thieves was a former security agent. “You can appeal to whoever you want, it will not give results,” they threatened over the phone. He also was offered 3 million sums as compensation for keeping quiet. He had to accept the offer, as the costly lawyers he consulted with earlier stated that he had hardly any chance of winning the case.

“I don’t have a social circle,” the young man concluded his account. He resides with his parents in Termez and sometimes commutes to Tashkent for job interviews. Now, the people who previously requested his services refuse to hire him. “You are afraid of ID checks, requests for additional certificates, and interaction with government agencies. Since my town is small, everyone knows everything now. They have labelled me unfavourably. It’s frightening.”

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect