“X”: photography project capturing lives of LGBTQ people in Kyrgyzstan

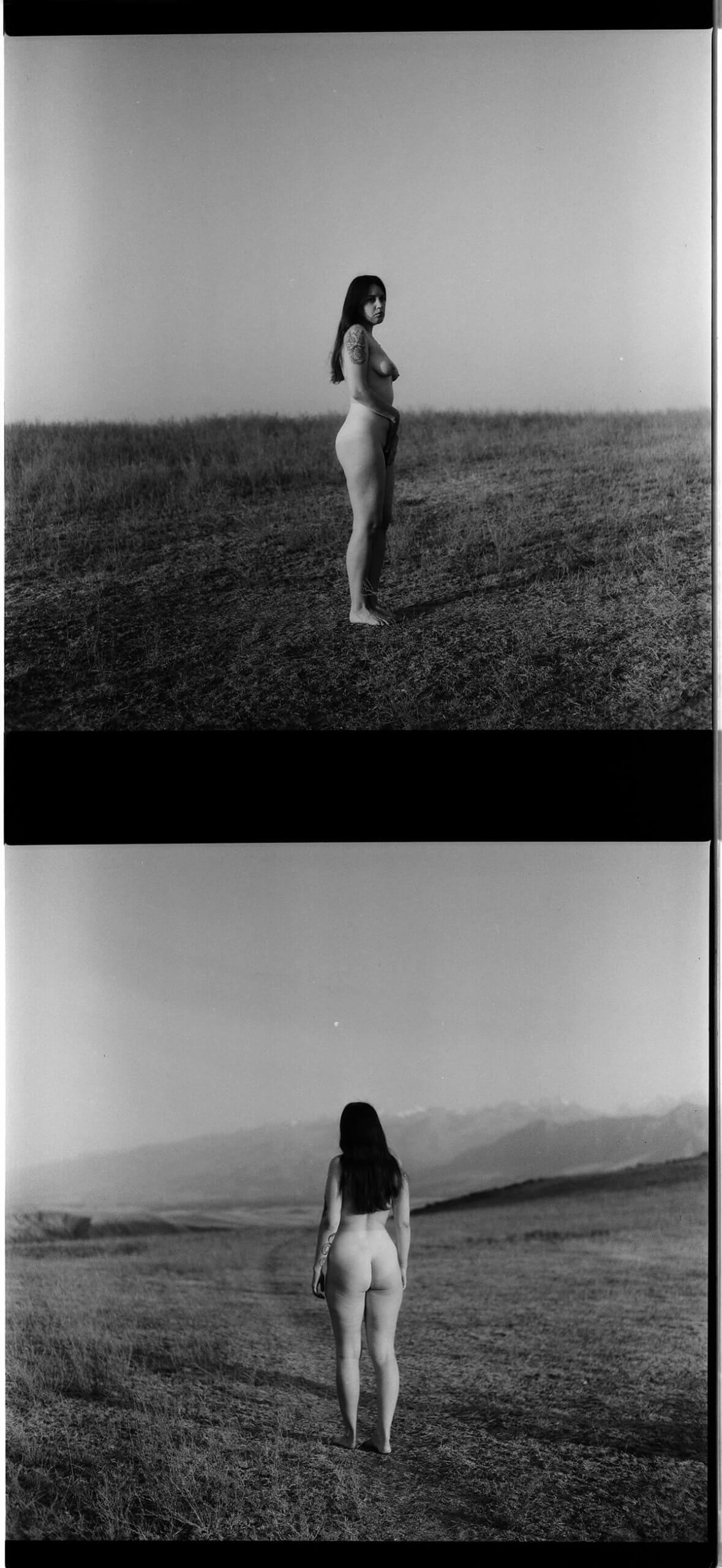

I spent three months in Bishkek shooting a photography project about LGBTQ people in Kyrgyzstan. I talked to subjects from different cities and different families. They were people of different ages and various professions. But they had one thing in common — a sense of insecurity about their identity.

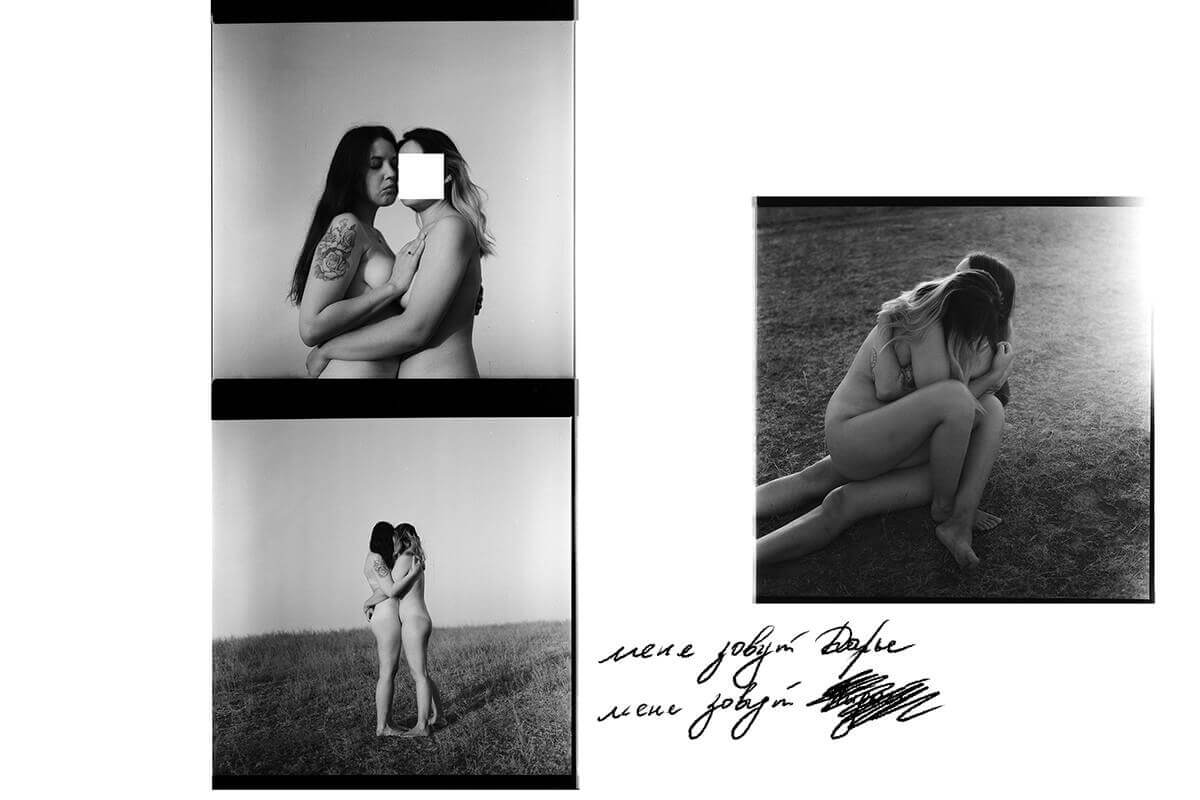

One of the stories of the project is that of my friend Daria and her girlfriend. We shared a flat, their relationship developed before my eyes, it was about someone close to me — all these factors, in a sense, made me a character in the story as well.

I had a chance to observe the intimate process up close and personal.

Although Kyrgyzstan is a patriarchal country with strong homophobic and transphobic attitudes, my friend and I felt safer than in our home country. This, on the one hand, opens up opportunities for solidarity and intimacy, but, on the other hand, puts us in a position of not belonging to any community. We were between two countries, two cultures. Rethinking the traditional opposition of Europe and Asia, we became convinced that this was not the only way to talk about the two regions, especially when they were united by a shared Soviet experience.

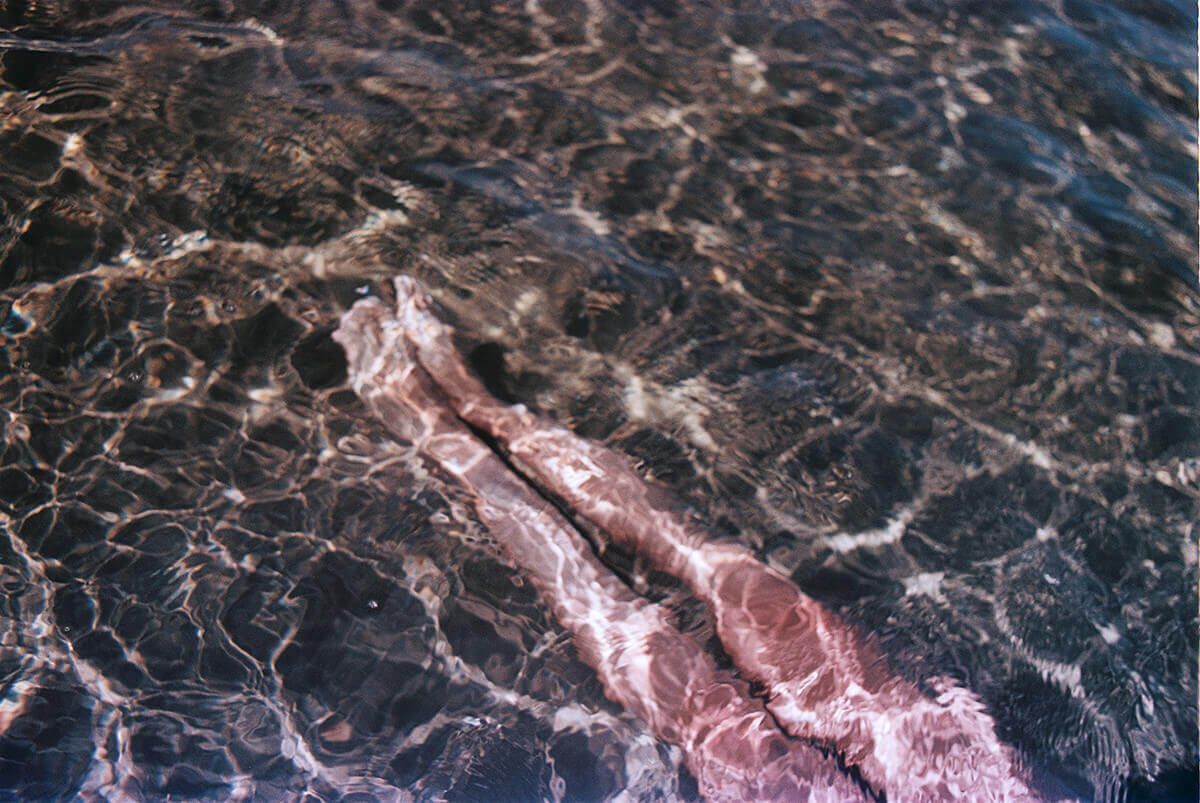

We talked a lot and kept silent a lot.

“I am a writer and an artist.

I’m a lesbian.

I’m also Belarusian.

I’ve spent the last six months in Kyrgyzstan because the girl I love is Kyrgyz”.

I start talking and I think: Here I am talking to you, Katya, my closest friend, my non-blood sister, but these words will be heard by other people, not just you. People I don’t know at all. I’m sure they are very different people. On the one hand, I want to speak at a high level of understanding, at a level where I don’t have to explain to anyone that I am human, that threatening me, insulting me, attacking me, taking away my job, whatever — is wrong. On the other hand, there will be people who will look at these photos and say, “I would put such people on a desert island, she is sick, I would kill them with my own hands, if it were my daughter, if she came into my grasp…” What should I do about it?

I can start explaining myself, making excuses. I can say, “You’re wrong about me. Homosexuality is not a disease, this is the position of the World Health Organization, the health care systems of both Kyrgyzstan and Belarus draw upon WHO documents, which means you cannot call me that. Here I have started — and I have run out of energy to go on because so many stereotypes (absurd, insulting, painful) are yet to come.

People don’t always choose to hear each other. They probably can’t always do it. The question is how it is expressed. You may not want to be friends with me. You may not approve of my life. But if it is OK for you to kill, to beat, to threaten, to insult, to bully, to deny the right to speak one’s mind, you are building a world of violence. In such a world, whoever is stronger is right, whoever is stronger is alive. Everyone else doesn’t matter at all.

The term “sexual orientation” is improper because it focuses on the physical, while we use it to talk about the social. When I say I’m gay, it doesn’t mean I want to tell everyone about what kind of sex I have. It means I want to share what all people share. Not to lie about dating a man or being single, but to tell the truth. Not to dodge the question or have a dread of casual conversations.

I’m sure these photos will be seen by people who share a part of my experience, my story. I would like to pass a supportive message to them, especially to teenagers and very young people who have become conscious of their identity and their future doesn’t look bright because of that. I am 26 years old, I have friends and acquaintances who will not turn their backs on me because of my identity, I have a family and my girlfriend is part of that family, I am fulfilling myself professionally and creatively while being open — which means that there is a place for you too in this world, that you can be happy too, you can be loved and accepted too.

“I am going to use the initial X to refer to my girlfriend. ‘X’ traditionally stands for the unknown or something that cannot be named.

“Being able to talk about oneself without hiding one’s face and name seems so easy. But in Kyrgyzstan, there are thousands of people who cannot do this because they are afraid of being beaten or killed. Is it possible to be proud of being capable of beating and killing? Apparently, some people can. I don’t know how people live with so much hatred and confidence that they can dictate to others how to live their lives.

‘Did you know that I’ve never held hands with anyone in public before?’ X asked me.

“Then one day she desired that I do not hug her too often openly. At first, I was angry at X, but then I realised that it was only right to be angry at the people who caused her to say that. To be angry at the homophobes, rapists and murderers who justify their unworthy animal anger with tradition.

“Many times in Kyrgyzstan I have heard stories of people being threatened by leaking their personal information and home addresses. The best play I have been to in Bishkek is staged behind closed doors because it was made by feminists — women who do not agree with violence and receive threats because of it. Why do men have the right to do these things? Why are women condemned and stigmatised for any reason, while the most heinous crimes of men are leniently glossed over?

“I really like Kyrgyzstan and I can say a lot of good things about this country and its people, but when it comes to the safety of LGBTQ people and women…

The value of human life in Kyrgyzstan is low. Violence is not a taboo, it’s a common practice.

Women’s lives are not worth anything at all, especially those of the LGBTQ community. Violence against them is even commendable.

Young people often want to leave Kyrgyzstan, even though there is splendid nature and many other wonderful things here. Perhaps money is not the only reason. Perhaps your children simply want to live in a safer society, where a kalpak on one’s head does not give one the right to beat, threaten and command.

What do you do to make your children want to stay?”

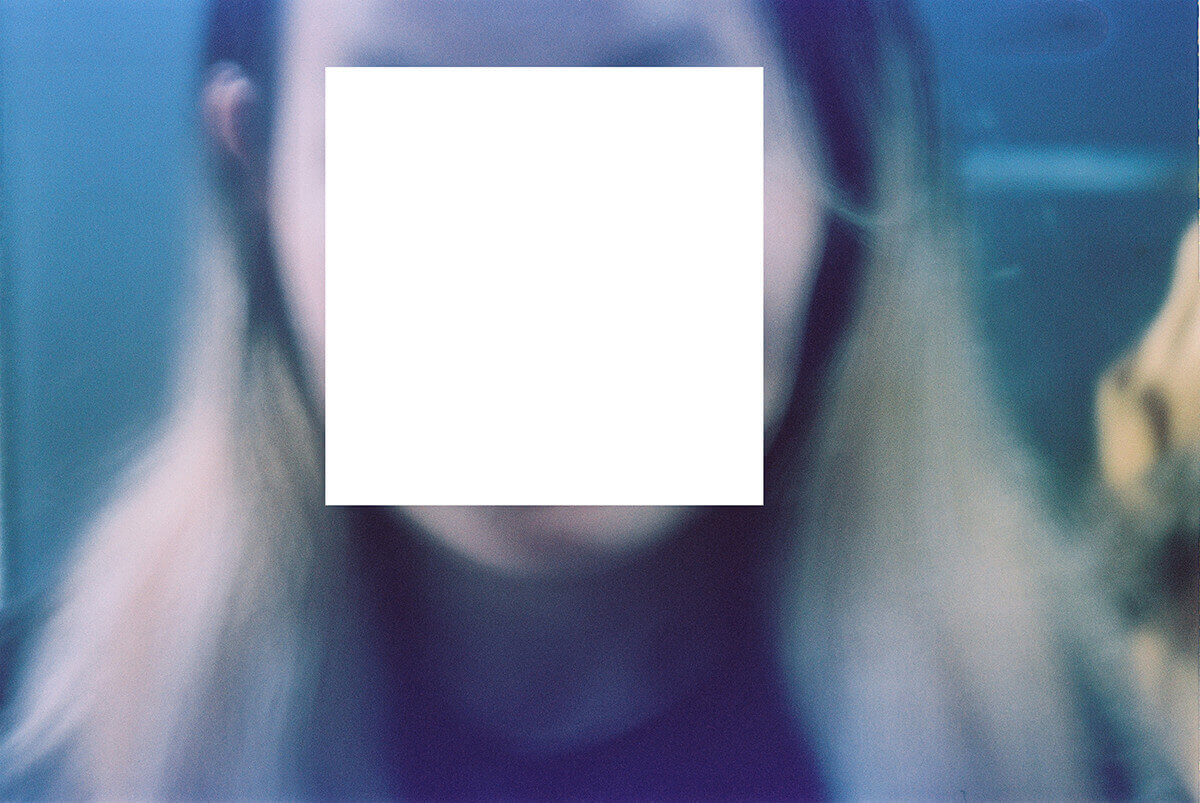

“What does it mean to me to have my face covered with a white square?

The safety of my romantic life in the first place. A guarantee that my private life remains private. A guarantee that I can decide who I want to get with without too much reproach or pressure from my family.

In Kyrgyzstan, family plays a very important role — I was brought up in such a way that my every decision has to be approved by my family. Otherwise, you are an outcast and a loner — without kith or kin.

Not that I need the approval of all dozens and hundreds of relatives, but without their approval, my parents cannot exist in this patriarchal and homophobic society. If I am publicly outed, I can move on with my life (at least go to another country) while my parents cannot. That is my responsibility. The white square is a guarantee of well-being for my parents, who link me with the whole country. I don’t care about the others, but I can’t give up on my parents. It would break my heart.

“Keeping them in safe ignorance is a blessing and a curse at the same time. They will never know how happy I am with my girlfriend, they won’t know that we are planning a family, they won’t know the main reason why I can’t stay forever in Kyrgyzstan, which I love so much. It breaks my heart every time my mother, pouring me tea and serving my favourite sweets, asks if I have anyone in my sights, and says the main thing is that I find my man for life, that I am happy, and my career and everything else will follow. My mother wishes me the best, but I already have that. However, it will be too hard on her if she finds out.”

This article was originally published here

Nothing beats good old email

For our monthly newsletter, we pick the most important news and analysis,

and add selected content and art from queer creators.