Valentina Salon: Beauty Practices of the Ukrainian Queer Community

This article was originally published in Ukrainian on TyKyiv

Anya at Pride in Bucharest. Photo: Anya’s Instagram page

Mariia Krychevska, a Kyiv native who now lives and studies in Berlin, began to notice how beautiful and well-groomed Ukrainians are. Strangely enough, a fresh manicure, ironed clothes, and a neat hairstyle on an unfamiliar woman on the street now unexpectedly remind her of home. For foreigners, this phenomenon seems strange — how can there be manicures during a war? — and at the same time fascinating, because the beauty industry in Ukraine has proved to be unbreakable.

Why is it so important for us to be beautiful? Mariia posed this question to people for whom self-expression through appearance is particularly important — queer Ukrainians, Anya and Matviy, as well as the owner of the Kyiv hair salon Valentyna. Their stories reveal the concept of a “safe space” for the queer community — and what it looks like in the context of the physical threat of war.

Despite the distance and differences in their experiences of moving versus living through the war in Kyiv, their reflections on beauty, self-expression, and the desire for safety intertwine and echo each other as an answer to the question: what place does self-care occupy in the lives of Ukrainians today?

The beginning of the war

Anya and Matviy met at a queer shelter for refugees organized in Bucharest by the Romanian NGO Accept. Anya is a lesbian, Matviy is a trans man and gay. They left Odessa at the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

“Queer people usually like decorative clothing styles, bright makeup, nails, and lots of accessories. It’s a way to express themselves when there aren’t many opportunities to do so.”

“Probably, if you asked the average European, ‘Do you know any queer Ukrainians?’, the answer would be, ‘Do they even exist?’. That’s why we want to make ourselves known, to say, ‘Yes, we exist’.”

About Anya

Anya is 36. Her journey to understanding her sexual orientation coincided with her migration. She was born in Luhansk, but moved to Odesa after the Russian invasion. In Luhansk, Anya was married to a man, although even then she was beginning to realize that she liked girls. “It was a terrible relationship — the kind that is difficult to get out of. It ended when the war started.”

In Odesa, Anya was alone for the first time — without her family, husband, or previous circle of friends. In the new city, she met a girl with whom she had a long-term relationship.

“I started to dress the way I liked. Before, when I was married, I wore tight dresses and heels — the way my husband wanted me to look. When we broke up, I started experimenting with style. I still like to look feminine, but not stereotypically sexy, more free, perhaps naive… More appropriate for my own gaze.”

Anya says that people abroad are used to having a simpler appearance, so she doesn’t feel the need to wear makeup every day to be “on par” with others. “Unrealistic beauty standards are good, but sometimes I miss that atmosphere when you go out into the city and everyone is so different and colorful. Each look is like a separate story.”

Photo from the protagonist’s personal archive

About Matviy

Matviy is 23. For him, feeling comfortable and beautiful in his own body is a lifelong quest. “I guess I haven’t reached that point yet where I feel 100% beautiful. But I accept my body — it is what it is, and I can live in it until I have the opportunity to change the things I don’t like.”

As a teenager, Matviy did not fit into gender norms and experimented with his appearance: “People tried to bully me, asking if I was a girl or a boy. Teachers called me Malvina when I dyed my hair blue. It’s funny — I changed my hair color, but the nickname stayed.”

After school, Matviy enrolled in theater college, where he studied costume design. There, he felt more freedom to express himself and met like-minded people, eventually joining local LGBTQ+ community organizations. In college, he often modeled for students learning hairstyling and makeup.

In Kyiv, there is a salon that is ready for such challenges. The Valentyna hair salon on Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street. Its owner, Valentyn, positions the salon as “new wave” which means no division between men’s and women’s haircuts, no templates, and no judgment.

Valentina Hair Salon. Photo: author

About Valentyn and Valentyna

Valentyn notes that when he developed the concept for the salon, he had exactly the target audience like Matviy in mind: “Our client is precisely the kind of person who has stopped going to the hairdresser because they constantly get the cuts they didn’t ask for.” The name of the salon is also ironic.

First, it’s a kind of kitschy way to play on the founder’s name: the name is easy to remember and sounds funny.

Second, “Valentyna” is about nostalgia, an allusion to the “Zhanna” or “Natalia” salons our mothers went to when we were little.

At first, Valentyn wanted to call the salon Home, and the name Valentyna is also about locality and, most importantly, comfort.

The salon’s approach is to be attentive to the needs and requests of its clients and to work together, where the client’s imagination and the hairdresser’s skill combine to create the perfect hairstyle.

Valentina Hair Salon. Photo: author

When asked whether Valentyna is a queer-friendly space, Valentyn responds thoughtfully: “Yes, but we don’t focus on that. It’s a personal choice, and it’s none of my business. On the contrary, as a stylist, I find it interesting to help clients highlight their sexuality and their image.”

Unusual requests, says Valentyn, are also an opportunity for hairdressers to show off their skills and talent, rather than cutting the same styles every day. He sincerely believes that a good hairstyle, while not solving all your problems, can trigger profound processes of change: “As soon as you change your hairstyle, you will see a different person in the mirror. This means that you will perceive yourself as a different person, and from there you can change your behavior.”

Valentyn first felt that his calling was to give people a fresh start with the help of hairstyles at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. At that time, he was working at the Gorodska hair salon, which was one of the first to open after February 24. “I cut people’s hair and see that they are happy. And different people came to us: from Solomyanka, where the first strikes hit, as well as those who were leaving Bucha, Irpin, older people. They come with their stories, and you have the opportunity to give them a sense of normality — so that they can look at themselves in the mirror and think, ‘Whatever happens, I look good.

That’s how he realized the power of his profession and decided to open his own salon.

Personal care and visits to the hairdresser help maintain a sense of normalcy. Beauty is unlikely to save the world, but it seems to help maintain sanity and create jobs. This is probably the definition of security for Kyiv residents who have become accustomed to functioning under shelling, because complete physical security is currently an impossible dream.

“We are also here (Valentyna hair salon) in a semi-basement room, which can be called ‘the nearest short-term shelter’ or ‘the simplest shelter’ — that’s us. (Laughs.) You can come in and just relax for an hour or an hour and a half and focus on yourself.”

Ada has been working as a hairdresser at Valentyna for about a year — since the salon opened. She says that, to her surprise, after heavy shelling of the city at night, the number of customers does not decrease the next day. On the contrary, people have an even greater desire to maintain their appearance in order to move forward with their lives: “They come to a space where other people work and live their lives, earning money for tomorrow, for rent, for their children, for leisure. People make plans and prepare for the future.”

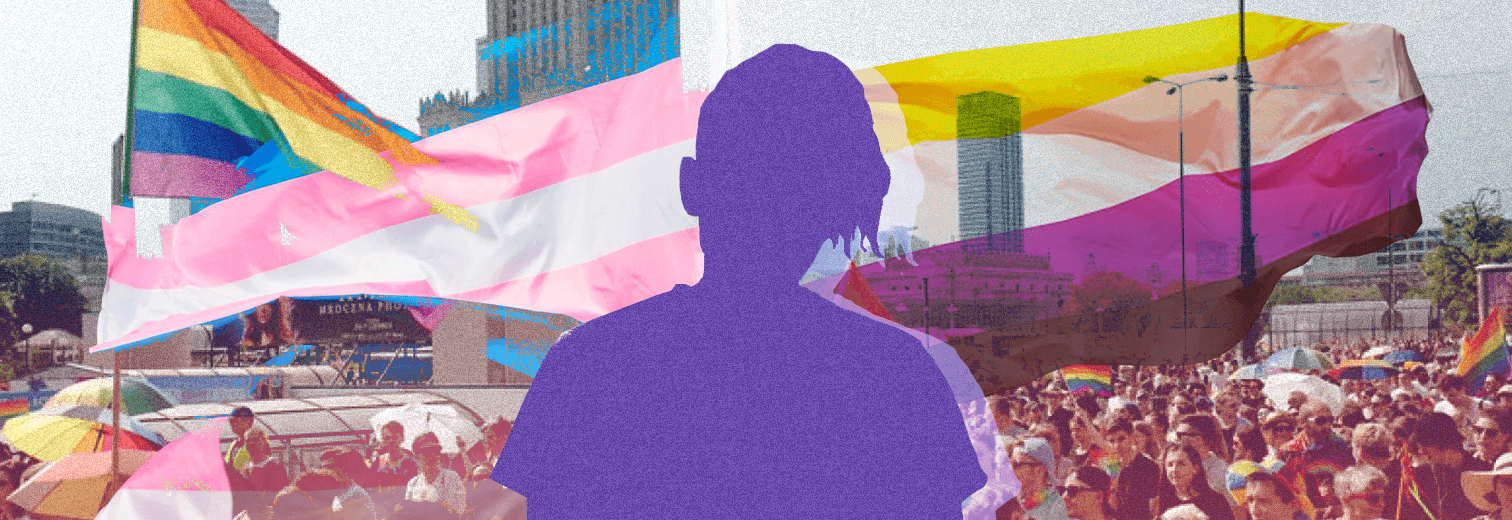

Although Anya and Matviy live in safety, they don’t have a place like Valentyna. They still feel like strangers in their new country of residence. Romania does not offer integration programs for refugees, so they have to learn the language on their own. Without fluency in the language, Romanians are reluctant to hire Ukrainians, not to mention the discrimination based on appearance or sexual orientation that is also present in Romania.

Despite this, the local queer community, which Anya and Matviy met through the NGO Accept, is very welcoming and friendly. Now they rent an apartment in Bucharest with their friends. For them, beauty rituals are a way to feel like themselves and stay afloat, so from time to time they organize a home beauty salon for their friends.

Anya says: “I do nails at home — I just taught myself. I can spend hours painting extravagant designs, anything my friends ask for and which probably wouldn’t be done in a regular salon. And Matviy does haircuts and hairstyles, all these ‘mullet’ styles, different coloring.” Matviy is also self-taught, but his services are in demand among his friends: “Sometimes it’s a nice extra penny, sometimes we agree on some kind of barter, or a service, or they ask, ‘Will you cut my hair, bro?’ — and I agree, that’s all.”

Feeling comfortable and beautiful, expressing yourself through your appearance, is a luxury that you should allow yourself, because self-confidence makes us more stress-resistant. Ada believes that in our time, especially during wartime, there is no place for discrimination. On the contrary, when we are all experiencing Russian attacks, the loss of loved ones, separation, and thinking about how to live on, we need to be more attentive and caring towards each other, rather than judging someone’s appearance or sexual orientation.

“There’s no need to stir things up — they’re already stirred up enough. We just need to muscle through and have the strength to support each other.”

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights