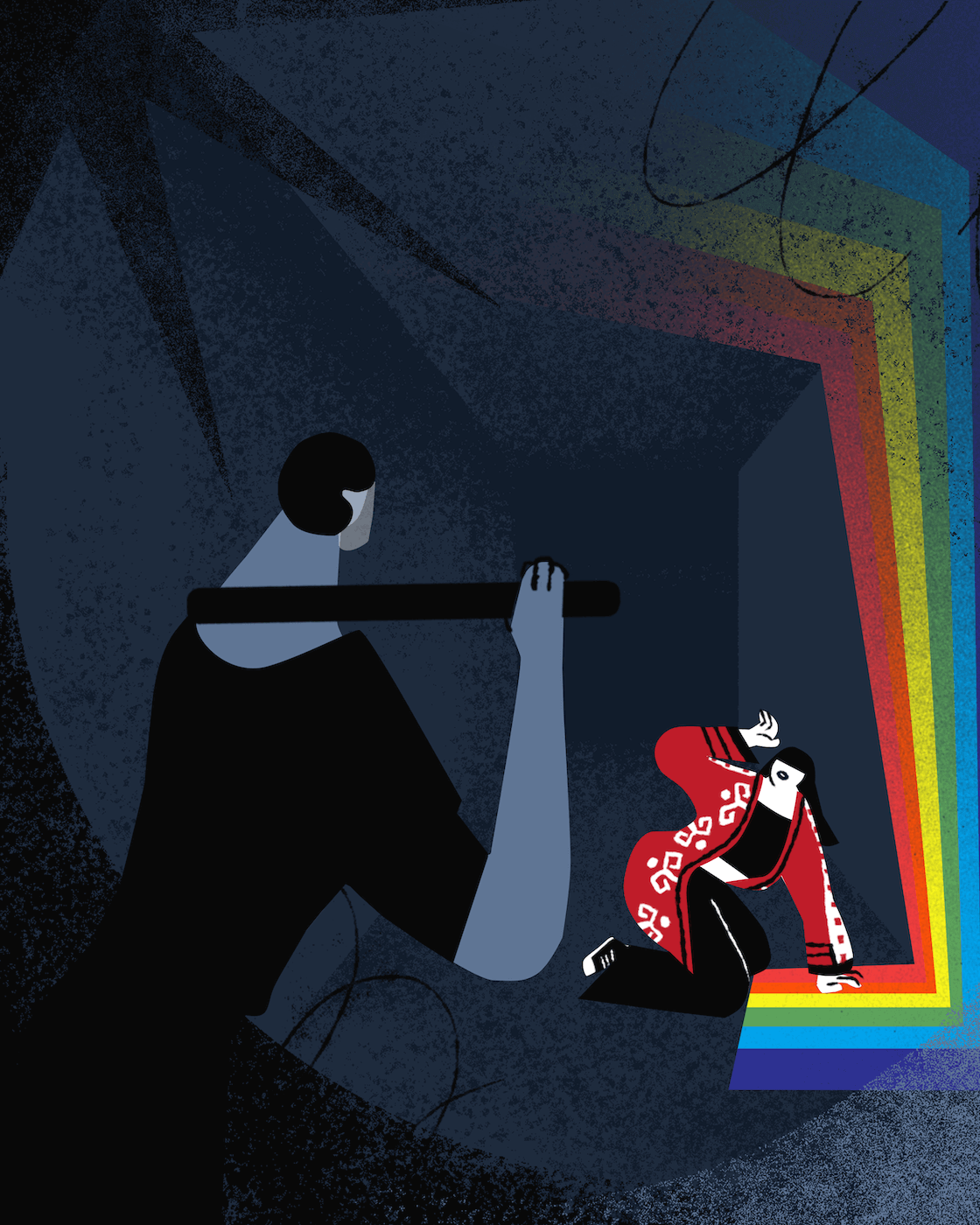

Trans Solidarity Against Bigoted Institutions

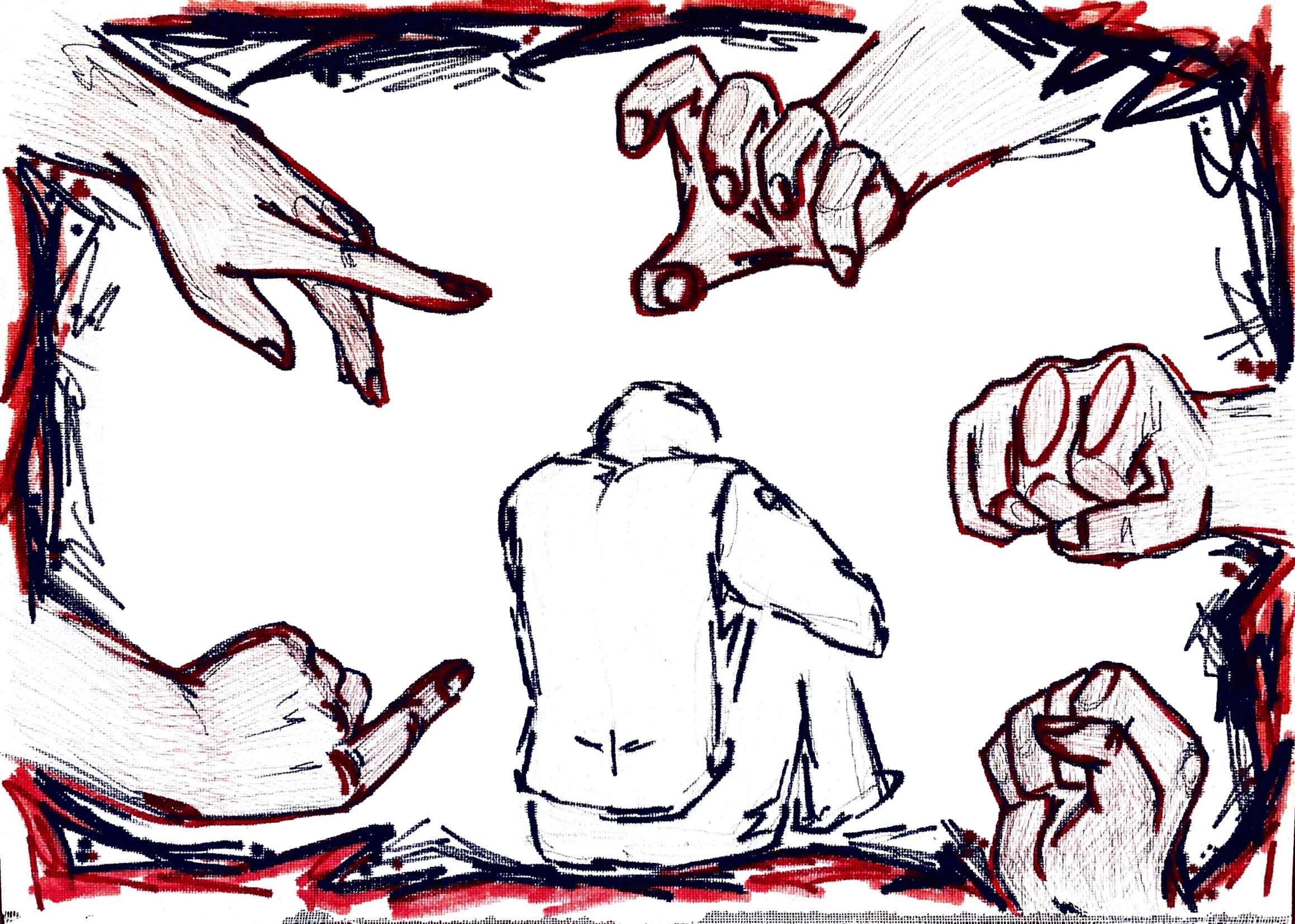

Trans individuals transitioning or wishing to transition in Azerbaijan face serious problems with healthcare workers who do not understand their needs, mostly provide ineffective treatment, and exhibit queerphobic behaviour. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and gender-affirming procedures are not easily accessible in the country, leading trans individuals to start hormone therapy without proper knowledge or guidance, putting their health at risk.

[playht_player width=”100%” height=”90px” voice=”en-US-ElizabethNeural”]

The absence of specific laws regulating hormone therapy and gender-affirming care exacerbates the difficulties trans people face, such as gender dysphoria, fear, and discomfort. Anti-trans policies are implemented in clinics in Azerbaijan regarding hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries. A few years ago, a renowned plastic surgeon in the country publicly opposed these procedures, labelling trans individuals as mentally ill. As a result, many trans people travel to neighbouring countries for more affordable and civil medical transition procedures.

However, upon returning to Azerbaijan, they encounter problems as their preferred gender identity is not reflected in their official documents. To change their gender marker, trans individuals usually have to undergo sterilisation and complete gender reassignment surgeries, obtain medical certificates verifying their treatments, and obtain permission from the court. Unfortunately, there is no established procedure for changing the gender marker in personal identification documents.

Differences regarding HRT accessibility between Turkey and Azerbaijan

Azad started transitioning in Turkey. It is much easier for local residents in Turkey to start hormone replacement therapy because they can apply to research institutes and hospitals, and the state helps them obtain HRT. Whether in Azerbaijan or Turkey, most trans persons fear starting the process without consulting a physician or clarifying the prices beforehand. Beginners rely on the experiences of trans individuals in their immediate social circles. Consulting a psychologist or psychotherapist takes a long time, often spanning one to two years. The majority start without medical supervision and the prices of hormones increase every year. According to Azad, in late 2021, he began HRT, and since January 2022, the prices have continued to rise.

“The prices of transmasculine hormone therapy are lower compared to transfeminine, and using them once every three weeks slightly reduces the financial burden. In Turkey, sometimes you have to visit 10-15 pharmacies to find hormones,” says Azad.

Azad hoped to find healthcare and initiate legal processes more easily in his home country upon returning from Turkey. According to him, initiating any legal process related to transitioning in Azerbaijan is only possible after completing the full transition, and the state only changes the gender marker on identity documents:

“It is known that the state closes all doors so that changing the gender marker on the identity document becomes either impossible or difficult.”

With the help of friends, Azad managed to find a doctor in Azerbaijan. However, while the doctor’s consultation fee was affordable, he mentioned that the examinations were expensive. The reason is that one has to go to a private clinic instead of state hospitals for any medical consultation.

“When I went to an endocrinologist in Baku, it had already been a year since I had been transitioning without a doctor. Even then, I wasn’t sure if the doctor had overcome their transphobia. It had been about a year since I started taking testosterone, and I didn’t believe that the endocrinologist would recommend increasing the dosage. I just wanted to make sure everything was fine with my liver and internal organs.”

During his four years in Istanbul, Azad did not undergo gynaecological examinations. When he sought advice from a doctor about gynaecology, the doctor understood that Azad is not a heterosexual trans person and their attitudes changed a bit.

“The doctor learned that I not only had relationships with cis-hetero women but also had penetrative relationships. After that, their attitude changed, and they became a bit hostile. They even said, ‘If that’s the case, why did you start transitioning?!’ They were confused about everything and couldn’t hide their phobia.”

Although Azad’s gynaecological examinations went smoothly, without encountering any queerphobia from the doctor, and the results were good, the high cost of private clinics and tests in the country makes frequent visits to doctors difficult.

When Azad went for a medical ultrasound examination in Baku, the doctor marked him as cisgender. All three doctors in the ultrasound room looked at Azad with surprise and uncertainty when he said, “Could you also look at the ovaries?”

“I told the doctor that I wanted them to check my ovaries, too. The doctor responded with surprise, ‘Do you want us to check your testicles?’ It was a bit strange.”

Azad’s personal challenges

Amongst the difficulties Azad personally faces in HRT is self-administering injections. According to him, he has to inject himself, which is not comfortable. Since testosterone is highly viscous, it requires using large needles, injecting deep enough and correctly. Otherwise, it causes a lot of pain, sometimes preventing him from sitting comfortably for days.

“After I inject myself, the place hurts for three or four days. I can’t go to the hospital and get injections. Even if the endocrinologist writes a prescription, doctors don’t do injections. I learned how to self-administer injections through practice and tutorials on YouTube. Even the process of injecting takes about half an hour. I stand in front of the mirror, and I have to draw a map to inject correctly. Each time, the question ‘Who will give me this injection?’ lingers in my mind.”

Azad hesitates to talk about the financial difficulties of going for gynaecological and endocrinological check-ups every three months, saying, “Unemployment is prevalent within the trans community, and access to medical services provided by the state is limited.” You need to see your doctor seldomly when you first start transitioning, however it’s important to see the doctor more often as time progresses. The effects of hormone use on reproductive organs change over time, and delaying check-ups is risky.

Obtaining hormones in Baku

For over a year, Azad had been using the Sustanon medication. After returning to Baku and undergoing medical examinations, doctors informed him that Sustanon was not available in Baku and suggested an alternative. However, he decided to continue with the medication he started with, which made accessing hormones even more challenging. During his time in Baku, Azad would bring hormones from Turkey through their acquaintances for himself and his friends.

One of Azad’s plans to make hormone therapy more accessible is to strengthen the existing solidarity and facilitate communication by creating a Trans Solidarity Group. Currently, the burden of communication falls on Azad because he has many acquaintances coming from Turkey. He believes that once the group is formed, this solidarity will expand further and benefit the trans community more.

According to Azad, it is only possible to obtain hormones from a single pharmacy in Baku. The medication needs to be pre-ordered and takes several days or weeks to receive. The price of hormones is five times higher compared to Turkey. A year ago, the hormone that cost 35 AZN in Baku was approximately 7 AZN in Turkey. Although hormones are slightly cheaper on the black market, they are still much more expensive compared to Turkey. Azad states that thanks to the solidarity networks created with friends and acquaintances travelling to and from Turkey, neither he nor his friends have resorted to the black market.

What can be done in Azerbaijan to expand access?

To expand access to hormone therapy, the state should ensure pharmacies provide hormones — they are not used solely by trans individuals, after all. Speaking about the government’s responsibilities regarding HRT, Azad says that the trans community in Azerbaijan needs allies to communicate with the state to address this issue.

“When trans individuals attempt to establish communication with the government, it can have a negative impact. The optimal scenario for me is when allies act as intermediaries in this matter. Currently, most of our potential allies are cis, especially feminists. And some athletes in Turkey use more testosterone, while here they use different steroids as substitutes. Perhaps athletes could also be allies.”

The inadequate support from healthcare professionals, limited availability of medical procedures, lack of regulatory mechanisms and laws further worsen the difficulties faced by trans individuals. To improve the situation, it is crucial for the government to establish regulations focusing on trans rights, provide inclusive healthcare services, and simplify the process of changing gender markers in identity documents. Collaborating with cisgender allies and promoting acceptance within society also play a crucial role in improving the situation for trans individuals. Taking these steps can create a more welcoming and favourable environment for trans individuals.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

“In Prison, They Named Me Rayhon”

From Street Violence to Stand-Up Scene

“The Most Important Thing For Me Is That My Son Is Happy”

“There Are Things One Doesn’t Choose”

“I Was Told I Had Disgraced Kazakhstan”

I Am Queer, but Am I Safe?

“If Your Protesting Hand Gets Tired, I’ll Be There To Take It”

“I Gave Up a Lot To Be Who I Am”

Influence

“If We Call the Police, They Laugh at Us”

In Armenia, Trans Community Faces Fear, Neglect