Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

The text was originally published in Belarusian on Hukanne

Upon returning to Berlin after the “Reframing Queer Narratives in Media” workshop and expressing my intention to write about LGBTQ+ individuals in concentration camps, I frequently heard questions. “Did it even matter? Aren’t the sufferings of all prisoners the same? Why bring up gender issues at all? What’s the point of comparing trauma?”

Such reactions are totally natural (it would be worse if people showed no reaction at all). However, after analyzing the current Auschwitz exhibition and reflecting on my visits to other memorial sites in 2023-2024, I saw the problem clearly: in many countries at the center of mnemonic institutions’ Holocaust discourse stands the male figure. In Poland, for example, it is the resistance movement member Jan Karski, ironically described by Dr. Aleksandra Szczepan as Polish James Bond, and Oskar Schindler, whose Krakow museum annually attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists; in Belarus – artist and three Nazi camps survivor Mikhail Savitsky. The authors of the most famous memoirs detailing the horrific Lager routine are Elie Wiesel (“Night”), Primo Levi (“If This Is a Man”), and Viktor E. Frankl (“Man’s Search for Meaning”). Regarding Stalinist repressions, which historian Galina Ivanova defines as “an undeclared, protracted civil war of the party and state against their own country’s peaceful population,” the most outspoken figure is that of the Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

With no intention to diminish the importance of these voices, one can still wonder: and where are the stories of others (or other stories)?

From Tolerance to Persecution

Homosexual contacts were recognized as illegal when the Prussian anti-sodomy statute as Paragraph 175 was included in the new German imperial criminal code after 1871. However, despite the ban, in the interwar period, the queer community was not only formed but also flourishing in many parts of the country with Berlin as its epicenter – a fact today no longer surprising. Actually, the very term “homosexuality” was itself an invention first introduced in the German language. Namely, it appeared as “Homosexualität” in 1869 proposed by the enigmatic author and journalist Karl Maria Kertbeny in a pamphlet that criticized the Prussian anti-sodomy legislation and argued for the recognition of homosexuality as an inborn condition.

In the 1920s, with a population of nearly 400,000, Berlin hosted a kaleidoscope of cabarets, homosexual, transvestite, and lesbian bars, balls, and nightclubs catering to gay clients. The vast majority of the estimated 80 to 100 gay venues remained open – well into 1935. Theaters had a rich repertoire of gay-themed plays, and gay-oriented publications (Die Insel, Die Freundschaft, Freundschaftsblatt, Die Freundin, Eros, Frauen Liebe, etc) were openly sold at kiosks. “There probably had never been anything like this before and there was no culture as open again until the 1970s,” notes Robert Beachy, a history professor and the author of “Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity”. He describes the late 19th-century atmosphere in the German capital as “homoerotic fraternization,” that made it possible for “warm brothers” to find “people like themselves and then also learn more about themselves”.

Homosexual contacts were recognized as illegal when the Prussian anti-sodomy statute as Paragraph 175 was included in the new German imperial criminal code after 1871.

Despite the use of linguistically “masculine” terms, sexual freedom extended to women as well – perhaps less visible but still present in the overall picture. In Berlin, popular clubs for ladies (Damenklub) included lesbian associations “Violetta” and “Monbijou” and the dance club “Monokel-Diele.” For example, in the 1910s-1930s, the Berlin variety stage featured the openly lesbian Claire Waldoff, known for her performances with a tie and cigarette.

With the tightening of legislation in 1935 (the paragraph’s draconian version would be preserved for a period of twenty years), persecution became harsher. “Even looking at another man the wrong way might get you in trouble. So, if there seemed to be some sort of homosexual, erotic intention, you could be prosecuted under the law,” specifies Beachy. Nazis considered homosexuals weak, unsuitable soldiers and useless husbands, and viewed homosexuality in general as a disease or behavior that could be both learned and unlearned.

Danish doctor Carl Værnet is infamously known for his experiments on homosexual prisoners. In 1943-1944, on Himmler’s invitation, he conducted “treatments” for homosexuality at Buchenwald and Neuengamme concentration camps by implanting in the men’s groins capsules with “a male hormone” that was supposed to change their sexual orientation. The experiments were not only scientifically unfounded but also extremely painful, leading to severe physical and psychological injuries, and sometimes death.

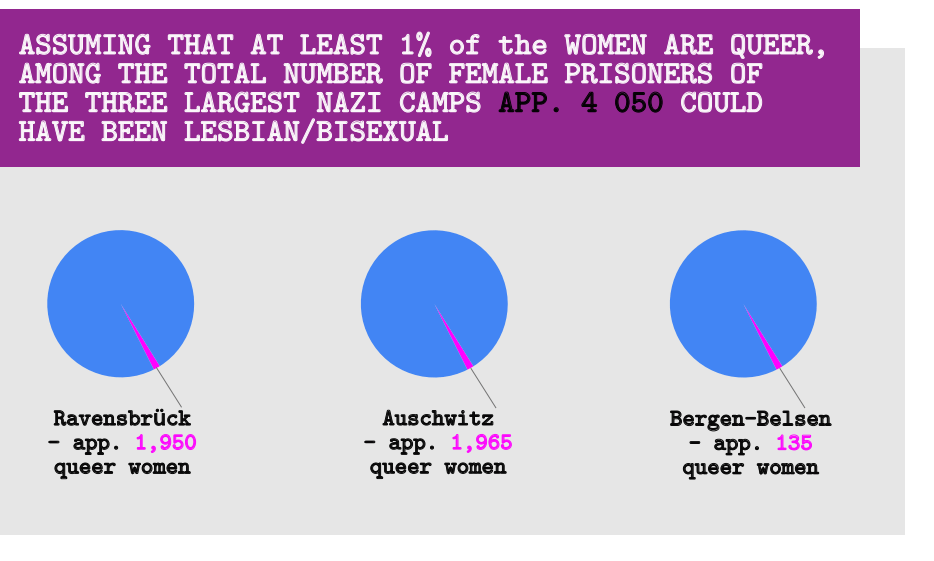

The exact number of homosexuals sent to concentration camps is difficult to determine. Despite Paragraph 175 and the “pink triangle” marking, which made it easier for researchers to identify their names in archives, and Gestapo interrogation protocols providing information about intimate contacts, geographical questions remain. Should annexed territories or homosexuals who went through prisons but were not deported to camps be included? Dr. Joanna Ostrowska argues that such cases actually make up the majority.

Joan Ringelheim, the Research Director of the Permanent Exhibition and Director of Oral History at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, cites a figure of “approximately 250,000 murdered homosexuals,” historian Robert Beachy mentions “more than 100,000 German men charged under Paragraph 175, and out to these an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 perished in prisons and camps,” modern German media – “about 10,000-15,000 homosexuals deported to camps by 1945,” while Dr. Ostrowska (keeping in mind the above-mentioned criteria) – 100,000–150,000. The truth is likely to rest somewhere in between.

The situation with “enigmatic information” becomes particularly problematic when we try to address the category of queer women prisoners.

Women’s Experiences

Due to the absence of any specific criminal law article that condemned intimate relations between women, queer females were not systematically persecuted by the Nazis who primarily saw them as women – that is biologically capable of fulfilling their primary function. However, it does not mean such contacts did not exist among camp prisoners. The thing is that queer women often were detained for other reasons the regime was more concerned about: as communists, Jews, Roma and Sinti, or criminals (in the latter case, marked with a black triangle as “asocial”). It should also be noted that girls or women could discover their attraction to the same sex already in camps without necessarily identifying themselves as lesbians or queer at all.

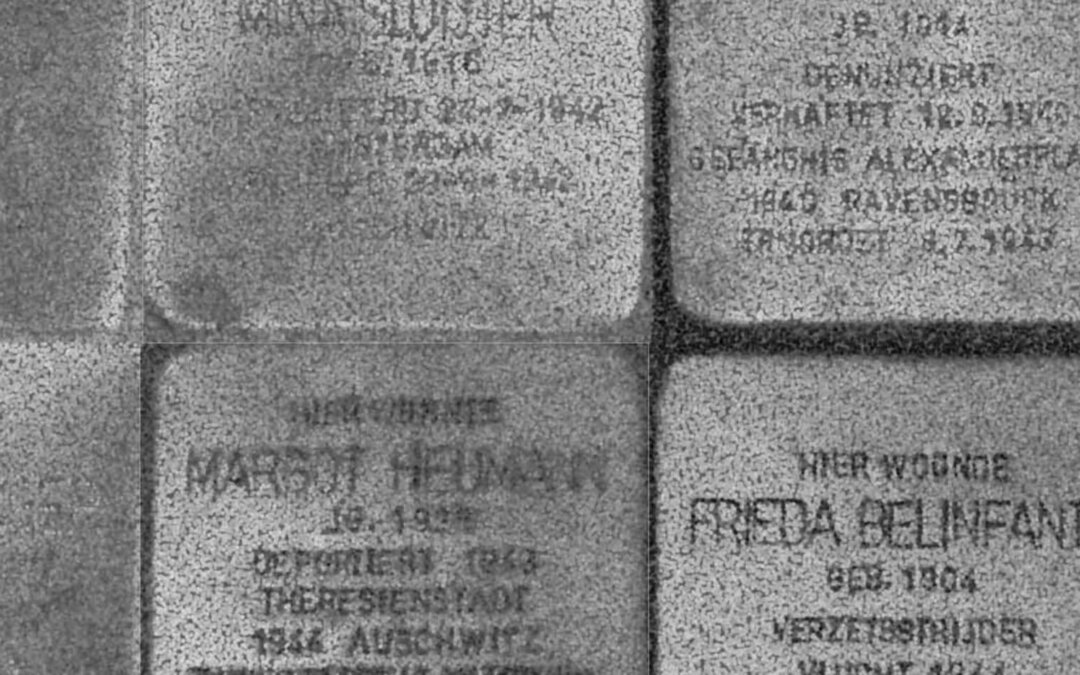

One of the tragic documented cases known to queer Holocaust scholars is the fate of Jewish lesbian Henny Schermann. In 1940, she was arrested and sent to the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp, where Nazi doctor Friedrich Mennecke, involved in the implementation of “T-4” euthanasia program, classified her as “licentious lesbian, only frequents [homosexual] bars,” leaving this comment on the back of her photo. The remark suggests that her subsequent transfer to the Bernburg Euthanasia Center, where Henny was killed in a gas chamber, was likely due to her sexual orientation rather than her Jewish origin. How many more queer women died in similar centers is now unknown – documented confirmation of sexual orientation found in case of Henny is extremely rare.

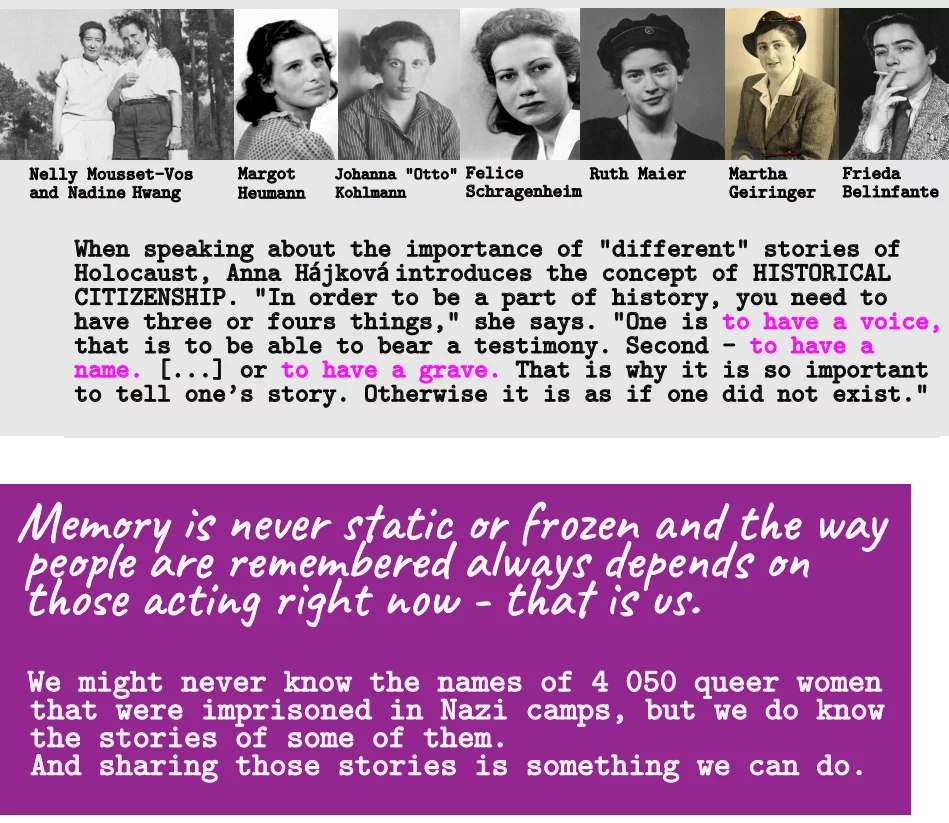

Due to the peculiarities of Nazi camp record-keeping and low research interest in non-obvious Holocaust stories, in addition to the masterly logic necessary for finding and comparing parts of prisoners’ biographies in order to trace their sexual orientation, literally the only source of information about the lives of queer women in camps are their memories: interviews, diaries, or (should we be lucky) books. However, here lies an even bigger problem – almost no one mentions intimate attraction to the same sex for example (check, for example, the vast archive of the USC Shoah Foundation with over 52,000 interviews with former prisoners). The reason, according to historian and Holocaust queer history specialist Anna Hájková, is the impossibility of discussing such topics within the “heteronormative framework of Holocaust research.”

Certainly, intimate relationships between women could not help but arise in camps or ghettos. However, due to the sensitivity of the topic and often also because of fear of judgment, few spoke about them later – just as few were actually ready to get such stories heard… “Such memory is not History; research has always focused on other voices and dimensions: political and national,” bitterly summarizes Dr. Ostrowska.

A vivid and rare example is Erica Fischer’s novel “Aimée & Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943” (1994) based on the story of the relationship between German housewife Lilly Wust and Jewish underground activist and poet Felice Schragenheim. Their rapidly developing romance led to Lilly’s divorce and a civil partnership with Felice in March 1943 – by then they had already been living together for several months. In July 1944, however, Felice got arrested by the Gestapo and sent to a transit camp, then to Theresienstadt and later Auschwitz. After her partner’s arrest, Lilly risked her life trying to secure a meeting with her – unfortunately, without success. Felice died in custody, presumably in one of the death marches between December 31, 1944, and March 1945.

In the last years of the war, Lilly continued helping Jewish women, hiding them from the Nazis. She would recall her first love for a woman and the awareness of her sexual orientation all her life (as romantic as it may sound today): in a 2001 interview, Lilly called the relationships with Felice “the most tender love imaginable”. “I never felt so alive in my life!” she emotionally confessed.

Another exception is the case of German lesbian Margot Heumann. In an interview given in 1992, she mentions her affection for a Viennese girl Dita Neumann, whom she calls “a very, very good friend.” Symptomatically, however, the woman still describes this teenage passion in terms of support and care, rather than attraction. Thirty years later, in another context and with a more sensitive listener, Heumann reflects on her experience much more boldly and through different vocabulary. In June 2021, her memories were presented on stage in the play “The Amazing Life of Margot Heumann.” (Director: Erika Hughes; Script: Anna Hájková, Erika Hughes)

Sexuality in camps was as changeable and complex as in the outside world. Some, like Felice Schragenheim and Henny Schermann, were aware of their orientation; others discovered their attraction after entering the camp and, perhaps like 14-year-old Margot, didn’t have the appropriate words for their new feelings. It’s also worth remembering that, regardless of circumstances, sex has always been an element of power dynamics. In the “picturesque fauna” of the concentration camp, people could also use sex and intimacy, in a broader sense, as tools to achieve this goal – physical survival – exchanging it for food, clothing, or the patronage of other prisoner groups or SS guards. “The fact that even in the most extreme surroundings, people sought human proximity, intimacy, affection and sex shows how much sexuality is a key part of human behaviour to the very end,” summarizes Anna Hájková.

This thesis is also confirmed in some testimonies of former female prisoners. Anonymously quoting one of the heroines, Joan Ringelheim writes, “S. did say that she knew of lesbian relationships and that ‘it wasn’t an issue; wherever you could get warmth, care, and affection, that was good. That was all that mattered.'”

Beyond Romanticization

Ringelheim also tries to warn researchers against romanticizing and heroizing women’s communities or so-called camp “families” – a phenomenon mentioned in the context of the female side of the Holocaust. It’s easy to stay at the level of recounting prisoners’ memories and praise women’s biological adaptability, their innate abilities to care and support each other. However, such an approach significantly simplifies the understanding of the subtleties of the microprocesses and dynamics of the camp’s Babylon. In the women’s community, there was care and support – but also there was homophobia, aggression, and oppression.

“Political and philosophical or conceptual errors are not far apart from each other,” writes Ringelheim. “The use of cultural feminism as a frame (albeit unconsciously) changed respect for the stories of the Jewish women into some sort of glorification and led to the conclusion that these women transformed ‘a world of death and inhumanity into one more act of human life. It was important, perhaps even crucial for me to see choices, power, agency, and strength in women’s friendships, bonding, sharing, storytelling, and conversations in the camps and ghettos, in hiding and passing’. […] And indeed, there are inspiring stories and people, moving tales of help, devotion, and love. However, they describe incidents and are not at the center of the Holocaust. They need to be put into perspective […] Oppression does not make people better; oppression makes people oppressed.”

Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, Buchenwald, Majdanek, Sobibor… as well as the network of camps organized by the Bolsheviks in the USSR, in the words of Hannah Arendt, “should never have happened.” However, the memory of this tragic chapter in world history has been instrumentalized by mnemonic institutions for decades, and the testimonies of prisoners – in addition to the natural distortions due to the memory’s elusive nature – pass through an ideological filter, risking romanticizing or heroizing the former prisoner’s experiences. In no way attempting to diminish the importance of the noble gestures that were daily displayed in inhuman conditions by those who managed to remain human in camps, we must nonetheless understand the importance of equalizing different stories. With the growing risk of the return of far-right regimes and the already established totalitarianism in Belarus and Russia, today more than ever we are obliged to ask uncomfortable questions of the past and present, hear and make heard “non-heroic” stories that should stop being discriminated against. The cost of silence may turn to be too high.

Read more from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

Valentyna Salon: Beauty Practices of the Ukrainian Queer Community

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights