Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

The text was originally published in Polish on Oko.press

Illustration: Anna Rzhevska

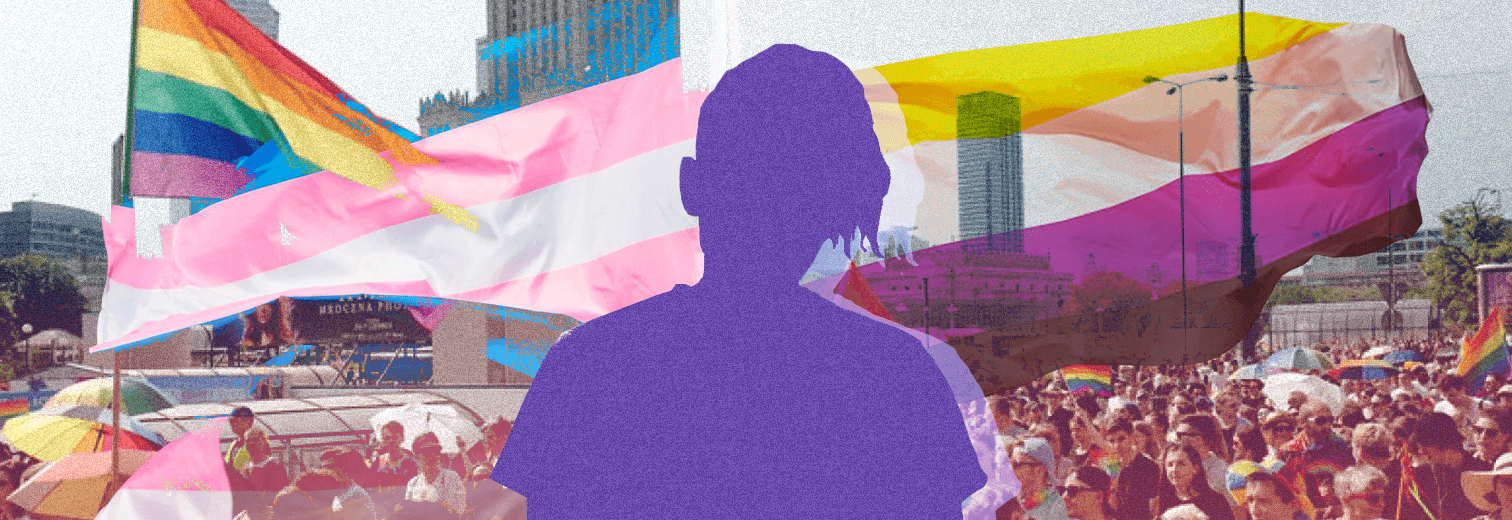

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, millions of people have been forced to flee their homes, looking for a safe haven. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 6.9 million refugees from Ukraine have been recorded globally (as of February 2025). According to the German Central Register of Foreign Nationals, there were over 1.2 million Ukrainian refugees in Germany as of March 2025.

It is particularly hard for the least protected population groups that had to leave their homes: elderly people, women with children, and other marginalized groups. Queer people are also a group at risk. Unfortunately, there are no statistics on how many Ukrainian refugees identify with the LGBTQIA+ community.

Even prior to the full-scale invasion, Ukrainian LGBT people faced many difficulties. Moreover, after the beginning of the Russian invasion of the East of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, many people became internally displaced persons. According to the study conducted by the research group of ILGA [International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association] Ukraine ranked 39th out of 49 European countries in terms of LGBT rights. During the war, LGBT rights are violated more often, with everyone lacking the opportunities to receive necessary medications, etc.

In our project, we decided to conduct a series of anonymous deep interviews with people who were forced to flee Ukraine due to war. We wanted to find out how they remembered their life in Ukraine, how they used to feel, and how their lives were changed by the war. We were interested in learning the most prominent challenges for queer Ukrainians in Ukraine and abroad they will name, and which adaptation and integration strategies they use as Ukrainian queer refugees in the new communities.

The authors discussed their research live on RadioBlau, a regional broadcaster based in Leipzig. Listen to the interview here.

For that, we chose the deep interview format. We interviewed 6 respondents aged 25-37 years who identify differently and reside in Germany, Poland, Finland, and Canada. Our respondents were born and had lived in the different corners of Ukraine. This way we can compare their experiences forged in different environments. To protect confidentiality, all names have been changed.

Participating in the interviews were:

- Serhiy, gay, 31 years. Was born in the Luhansk region, lived in Kharkiv and Vinnytsia (Ukraine). Currently resides in Krakow (Poland).

- Martha, nonbinary bisexual, 36 years. Was born in Kryvyi Rih, lived in Dnipro and Kharkiv (Ukraine). Currently resides in Leipzig (Germany).

- Vitalii, gay, 37 years. Lived in Lviv (Ukraine). Initially moved to Krakow, currently resides in Calgary (Canada).

- Anastasiya, bisexual/ pansexual, 28 years. Was born in Simferopol (Ukraine, Crimea). In 2014 due to the Russian occupation of the Crimean peninsula has moved to Lviv, and later to Vroclav (Poland). Currently resides in Halifax (Canada).

- Kostyantyn, asexual homoromantic, 25 years old. Was born in the Vinnytsia region, had lived in Odesa (Ukraine). Currently resides in Oulu (Finland).

- Olha, bisexual, 31 years. Was born in the Donetsk region, lived in Kharkiv and Donetsk until 2014, had moved to Kharkiv due to the Russian occupation of Donetsk. Currently resides in Warsaw (Poland).

Their memories of Ukraine were filled with nostalgia. The respondents explained it by the feelings around lost home, friends, and loved ones. The war made them leave their relatively comfortable or at the very least familiar environments. This period in life was the time for them to come to terms with their identities. Due to the taboo nature of these topics, almost all of them have struggled with internalized homophobia at the acceptance stage.

Map: Andrii Shestaliuk

Anastasiya (Simferopol, Lviv), 28, bi:

“When I still lived in Ukraine, I was quite young and couldn’t fully understand what was happening to me. I had some feelings I could not explain, but I lacked the information that would tell me about other options aside from loving men. I didn’t even know what to call it and how to identify myself.”

Vitalii (Lviv), 37, gay:

“My Christian upbringing has given me internalized homophobia since I was a child. I believed there was something wrong with me, and I had to do something to combat this. At the age of 26, I gathered the courage to register on the dating site for the first time. I met a guy there who experienced similar feelings. Together we found a community of men who stated that by working on your masculinity you can somehow reduce the sexual attraction to your gender and increase the attraction to the other gender [a form of conversion therapy – ed.]. At a certain point in my life, I belonged to this community.”

Though they didn’t experience physical violence, all the respondents mentioned everyday homophobia and negative stereotypes regarding LGBTQIA+ that came from the family, friends, and work environment.

It manifested both in “innocent” jokes and a direct invasion of private life. Due to these reasons, none of the respondents felt safe and lived openly in Ukraine. Most of them were only able to come out abroad.

Illustration: Finn Hofmann

Serhii (Kharkiv, Vinnytsia), 31, gay:

“I felt that it was a social taboo, that it was something wrong. I always used to hide in Ukraine. I felt that it was life-threatening. And I couldn’t even imagine that one day I’ll be able to openly express myself.”

Anastasiya (Simferopol, Lviv), 28, bisexual/pansexual:

“People from my friend circle favored the traditional values. According to them, feminism is worse than fascism, and if you are a feminist, you must be a man-hating lesbian separatist.”

Vitalii (Lviv), 37, gay:

“I didn’t face any homophobia, aside from people saying something bad in my presence which offended me. But they didn’t know about my orientation and didn’t have the slightest idea they insulted me. Well, I didn’t dress extravagantly, you couldn’t guess I am gay from my look. And I was behaving “normally”. Maybe that’s how I managed to evade physical aggression.”

Kostyantyn (Odesa), 25, asexual homoromantic:

“When the principal [of the school where I used to work – ed.] learned that I am a queer person, she demanded that I didn’t speak up on the topic anywhere, never mentioned it. She made me close my Facebook page, so I filed a complaint to the municipal Department of Science and Education, reminding them that the law prohibits the discrimination of MOGII [marginalized orientation and gender identities – ed.] in the workplace. I ended up not closing the page and kept posting what I wanted.”

Such tendencies also affected their family lives. All of the respondents recollect that they spent much time preparing to come out to their parents. Only Martha’s parents were accepting.

Serhii (Kharkiv, Vinnytsia), 31, gay:

“[My family] had a deep-rooted homophobia. When I lived in Poland, I came up to my mom, and she seemed to be OK with that. No hysterics, no negativity. But afterward, she didn’t broach the topic, not even once. Almost 7 years later she still ignores it. I wouldn’t call it homophobia, but that’s not healthy either.”

Vitalii (Lviv), 37, gay:

I gathered the courage to come out to my parents and brother. They got my permission to share the information with other people if they need a shoulder to cry on…

Anastasiya (Simferopol, Lviv), 28, bisexual/ pansexual:

“When I told my parents [about myself], they were OK with that, to the extent people raised in the hyper-patriarchal environment in the USSR can be OK with that. But it still felt extremely uncomfortable. I believe that no matter what your parents are like coming out to them is one of the most unpleasant experiences.”

Kostyantyn (Odesa), asexual homoromantic:

“At first my mom cried, worried and even took me to a psychologist once. She told me about a sailor she had been “curing” from homosexuality for 8 years. And I said that according to the ICD-10 [International Classification of Diseases – ed.] it is not an illness, and that she is a fraud. That was the last time we came to her.”

Negative tendencies regarding the perception of LGBT people in the Postsoviet countries are further aggravated by inherited Soviet patterns and lack of adequate information in the media, on TV; controversial statements voiced by the opinion leaders, such as church leaders.

The Ukrainian situation started to change only in the middle of the 2010s. The respondents noted a significant shift after the Revolution of Dignity in 2014.

Illustration: Finn Hofmann

Martha (Dnipro, Kharkiv), 36, nonbinary bisexual:

“Back then we lacked the information we have today. My formative years as a bi person were at the beginning of the 2000s. But actually, one can say that there were many more texts about men, and I was less aware of relationships between women compared to gay relationships. That was also weird.”

Serhii (Kharkiv, Vinnytsia), 31, gay:

“I didn’t know much about the [LGBT] movement. I learned something myself, learned something at the friendly doctor’s appointments, where I could take express tests for all STIs. Soon after the Revolution of Dignity I moved to Poland, because the war had started, and my home was occupied. I believe it was around that time, in 2016-2017, when the first Pride parade was held [in Kyiv]. I also remember attempts to organize something similar in Kharkiv.”

Kostyantyn (Odesa), 25, asexual homoromantic:

“Thanks to the information on the internet [in English] I was convinced that I was right, and being gay is OK. Around [20]16 it began getting better which is evident from the polls. According to the official data, 8 thousand people came to Kyiv Pride in 2019. I believe that if not for the coronavirus and the war, up to 20 thousand people could come. The Revolution of Dignity has led to profound changes. As we remember, in [20]11-[20]12 Ukrainian Parliament tried to pass laws on so-called “gay propaganda”. Since then we have come so far that LGBT people are now being invited on the state TV channels and other media resources to speak about their rights.”

Despite that, a lack of awareness of diversity in the queer community sometimes leads to phobias persisting even inside the LGBT community itself. At times, people facing such prejudice can be “denied” the right to belong to the queer community.

Martha (Dnipro, Kharkiv), 36, nonbinary bisexual:

“I didn’t even know that biphobia was a real thing before I got involved in the LGBTQ+ community. But it was a lesbian community where I faced this particular phobia which implied that if I am bisexual, I am… faulty I was told that bisexual women will definitely leave a lesbian for a man, that they want dick, etc. Truly horrible things.”

Due to the war, many people from the LGBTQI+ community were forced to flee their homes. Most of the refugees had to move more than once.

Illustration: Finn Hofmann

Anastasiya, bisexual:

“Oh, moving to Canada was really taxing, both emotionally, and physically, as well as financially. It has made a huge hole in my budget that I filled for about a year. (…) My moving to Canada was directly connected with the end of my previous relationship. I also dated a girl, she is Ukrainian, but we lived in Poland. At the time, her parents also moved from Kharkiv to Poland, and that was just… it was so dramatic.”

Adaptation, studying a new language, and searching for a job are hard. There are certain indicators of success in the immigrant community: for instance, when a new immigrant has local friends (Germans, Canadians, Poles, etc.) or understands and uses slang words.

However, in reality, even those deemed “almost Germans” or “almost Poles” still get marked as foreigners in the broader societal context, othered by the tiniest language mistakes, habits, or political views.

To a certain extent, these stories show how Europe functions as a unified space, not formally, as a European Union, but in the older sense: the person wanders Europe searching for safety, community, and home.

We say “to a certain extent” because some of the respondents ended up in Canada. Historically, for many Ukrainians Canada is part of the myth of happiness found somewhere over the rainbow.

Due to significant limitations in Ukraine, LGBT people often think about moving abroad, where their rights would be fully or at least somewhat protected, and they will get the chance to live freely, without fear. Most people we interviewed also contemplated this. However, the necessity to flee from the enemy missiles shedding from the sky on all Ukrainians is a truly atrocious impetus for emigration. That is yet another Russian crime because when Ukrainian queer people were forging their better future, it was Russia that caused the movement enormous damage. It is really hard to improve human rights situations in times of war. We need to keep this in mind when criticizing homophobia and building future plans.

Olha (Donetsk, Kharkiv), 31, bisexual:

“I am a refugee now. For the second time already. Before that, I had been an internally displaced person in Ukraine. [Home is] such a distant memory, which keeps fading over time. On one hand, I learned to make any place feel like home. On the other hand, I don’t have a place that I call home. Anywhere.”

Read more from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

Valentyna Salon: Beauty Practices of the Ukrainian Queer Community

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

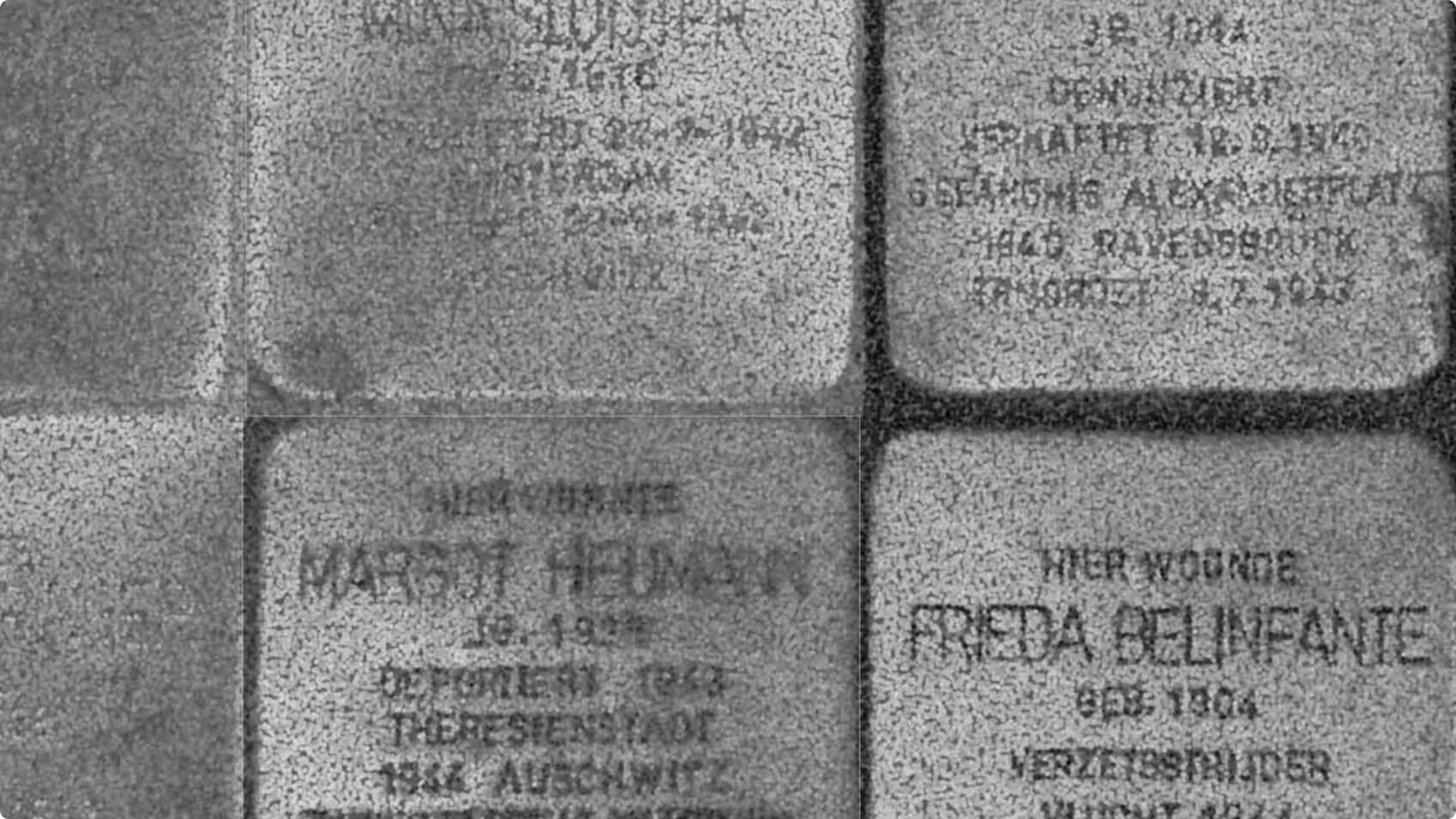

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Queer Fronts

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights