Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

This article was originally published in Ukrainian on Vilne Radio

Collage: Vilne Radio

In the United States and Western European countries, LGBTQI+ rights movements became mass phenomena as early as the 1970s, when the first large-scale pride marches took place in the years following the Stonewall riots. But this was not the case in the Soviet countries. In Ukraine—and in the Donetsk region in particular—changes began only after the country gained independence. However, with the occupation of parts of the region came a new stage of persecution in certain areas.

For this article, we conducted in-depth interviews with activist and co-founder of one of the first LGBT centers in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, Andriy Kravchuk, as well as with Serhii K’yartan, a gay man from Mariupol who grew up and came of age in Donetsk region during the early years of Ukraine’s independence. We also consulted several other community members from different cities. Additionally, this piece includes references to studies on community life in the region at that time and articles from local media outlets.

Ukraine was one of the first countries to decriminalize same-sex relationships

December 12, 1991. Just a few months after the declaration of independence, Ukraine became the first of the former Soviet republics to abolish the criminal penalty for same-sex relations. This change did not come as a result of activism, yet its significance can hardly be overstated, recalls Andriy Kravchuk, co-founder of one of the first LGBTQI+ organizations in Donetsk and Luhansk regions, “Nash Svit” (Our World). The organization was registered in Luhansk in 1998, but worked with people from both regions.

“It was a momentous step. You didn’t have to worry about being thrown in jail for your personal life, for something that other people have no right to interfere with at all. In Soviet times, you were a criminal simply by the fact of your existence. And the fact that Ukraine did it first was really quite by chance”, says Andriy.

Andriy Kravchuk, co-founder and advocacy expert at a human rights LGBTQ+ center “Nash Svit” (Our World). Photo: Vilne Radio (Free Radio)

In the 1990s and early 2000s, gay, bisexual, and lesbian people mostly did not use these labels for themselves, and often did not even identify that way internally. This is confirmed both by all the interviewees in this story (men and women alike) and by some of the few articles available online. For example, in a 2009 interview with the Kramatorsk gay man published by the outlet Skhidnyi Project, he said: “…80, if not 90% of my sexual partners were not actually gay, but heterosexual, ordinary men. I’m friends with gay men, but I rarely sleep with them”.

Andriy Kravchuk explains it this way: “People used to resist such labels.”

“When homosexuality is associated with something dirty and criminal, acknowledging yourself as an LGBTQ person is first and foremost a challenge for oneself.”

“People didn’t want to call themselves by these terms. The same still exists today in repressive societies, where there are certainly gay men and lesbians, but they do not identify as gay or lesbian”.

“We didn’t have anything to help us become self-aware”

In the first two decades of independence, LGBTQI+ people in Ukrainian Donetsk became aware of and understood themselves while being surrounded only by information from print media, television, or their immediate social circles. And there, the necessary resources were lacking. Most of what the press published about LGBTQI+ people were scandalous reports: “It was even interesting to read, because any information is better than none, but honestly, it was unpleasant, because we realized how distorted the picture was”, recalls advocacy expert at the “Nash Svit” (Our World) Center, Andriy Kravchuk.

Mariupol resident Serhii K’yartan says something similar:

“[At that time] it was about self-awareness in the complete absence of any role models. Gay life was glamorized. For example, everyone knew about the big ‘icons.’ Within the gay community, these were women from the Russian pop scene (like Gurchenko, Pugacheva, and later Lolita); if from Ukraine, it was Iryna Bilyk. They were always women as patrons. They acted as allies, but never truly represented an actual role model. And the role models promoted by the media, which shaped some general perception [in society about who gay people are], were personalities like Philipp Kirkorov — in other words, completely burlesque, histrionic, unstable figures, constantly accompanied by some scandal; something was always off with them…”

Serhii K’yartan, Mariupol resident. Photo from personal archive

Mentions of lesbians or bisexual women in the press or on television in the 1990s and 2000s, if they appeared at all, were mostly in comedy shows or in pieces where “lesbianism” was presented as a sensational, eroticized, or scandalous topic. Female homosexuality was often discussed as a joke or a “fetish” for men, our interviewees recall. At best, role models could be strong, independent heroines from film or music — for example, singers known for rebellious behavior or openness — but without any direct identification with LGBTQI+.

It was only in the mid-2010s that the situation began to change: information became more available, and stigmas decreased.

On transgender identity, Andriy Kravchuk from the human rights LGBTQ+ center “Nash Svit” (Our World) says: “In the USSR, sex reassignment was allowed. It was difficult, but possible. However, there was no transgender or non-binary identity. People felt either as a man or a woman, and the only issue was aligning their appearance with their feelings. People obtained permission, underwent the appropriate surgeries, and continued living as a person of the other sex.”

At the same time, non-binary individuals were unknown, and there were no terms for them.

How gay and bisexual people met in the Donetsk region before the internet was made

The period between 1991 and 2014 for LGBTQI+ people in Ukraine was a time of gradual transition from a practically underground life to openness. During this time, people still used the methods of meeting others that had existed in the Soviet era of criminal prosecution, but new, more open and even somewhat public ways were also gaining popularity (though still only to a certain extent).

Dating services, newspaper personal ads, and the first internet websites

Decriminalization allowed homosexuality to be mentioned relatively freely in the press. Thus, in Ukraine, as early as the early 1990s, the first newspapers and magazines with erotic content appeared, including personal ads. Starting in 1992, the Latvian erotic publication Sex-hit began circulating in Ukraine, featuring a separate page for lesbians and gay men with corresponding personal ads. Some Ukrainian newspapers also began publishing personal ads for men seeking men and women seeking women, particularly in regional newspapers such as Donetsk’s Salon Dona i Basu and Luhansk’s Ekspres-Klub. In the cities of the Donetsk agglomeration, the local classifieds newspaper Allo was also popular. Even in newspapers that did not openly support publishing same-sex personal ads, such ads still appeared. Gay men and lesbians would write “heterosexual” or neutral text, but include coded phrases and hints that were understood by those who were interested.

The first issue of the Donetsk magazine Salon Dona i Basu in a private collection. Photo: “Hovoryt Donetsk”

Apart from seeking connections through newspapers, in some cities during the 1990s, a few enthusiasts created “dating services.” The organizers maintained small databases of people from different cities. In the Donetsk region, such a service existed for a while in Mariupol. As noted in the study LGBT Community of Ukraine: History and Present, the work of these dating services “was not profitable (at least, even the attempts at commercialization failed) and partially satisfied the huge demand for personal contacts.” Later, when personal ads in newspapers and magazines became significantly more popular, these “services” disappeared. They were used more often by men.

“When women met, it was, for example, in cafés known as places where you could [meet another woman]. Or simply through acquaintances — that was the most common way to meet someone: you’d get to know one person, then she would introduce you to someone else, and then another… through personal connections”, adds Andriy Kravchuk.

Women most often met through their friends, recalls our interviewee Iryna (name changed at the speaker’s request), originally from the Kharkiv region. She describes the first decades of independence as a time when, due to society’s generally dismissive attitude toward female homosexuality, heterosexual men often failed to understand rejection. As a result, lesbians frequently faced sexual violence. Among bisexual women, it was common to ignore the part of their feelings directed toward other women and to choose the socially accepted path of relationships only with men.

By the late 2010s, dating gradually began to move online. It did not replace all previous ways of finding “your people” among the LGBTIQ+ community, but it continued to develop. Describing the year 2006 in Mariupol, Serhii K’yartan says: “The Internet was still lagging behind. At that time, it was very difficult to find someone online who had a page with a photo — and for that photo to actually be of them. Moreover, there weren’t so many different separate online communities yet. On dating sites, everyone was there — both straight and LGBTIQ+. So being there was very dangerous for us: we could be ‘outed.’ And no one was coming out back then. Besides, the connection was expensive, the level of internetization was underdeveloped, and even the very culture of online dating was still weak. That’s why it was very difficult to meet someone online — we met mostly through acquaintances and at parties”.

Serhii himself had an unpleasant experience with online dating back when it was not yet common.

“That’s where [on the internet] I got caught for the first time. I was sitting in the computer lab at the department, browsing a dating site, and then a girl from my class walked in and said, ‘Hi, Ihor.’ And I knew my name wasn’t Ihor — my name was Serhii. Then it hit me that I had registered on that site under the name Ihor. And that’s when the whole dictatorship-blackmail thing began. That’s when I realized how extremely uncomfortable I felt — rumors about me started to spread, and I was powerless to respond to them or to feel functional as a student”.

The book Being a Lesbian in Ukraine: Gaining Strength by Laima Heidar and Anna Dovbakh, published in 2007, provides the following quote about dating during that period: “For women who have relationships/sex with women, meeting places or dating sites are important. The initial desire to find others like themselves and to feel safe in a certain place in the city is a basic need expressed by the majority of girls”.

Most same-sex dating websites that gained popularity by the late 2000s and early 2010s were Russian. These were old, “wooden”, as our interviewees call them, websites that have long since lost their relevance. Very often, one could only find someone from other cities there, as the number of users remained small. And for residents of smaller towns, these platforms were even less effective.

LGBTQ+ Venues in Donetsk Region Since the Beginning of Independence

The history of legal gay discos and nightclubs in the Donetsk region dates back to the early 2000s. At that time, for the first time, special themed events began to be held on specific days at the Galaktyka nightclub. Literally that same year, the idea of hosting such dedicated nights was adopted by other venues — including the Russian Club located in the Puppet Theater building and Club Donetsk, as noted by the authors of one of the reports from the LGBT Center DonbassSocProject.

In the 2000s, gay and lesbian parties were becoming increasingly popular. In 2008, such events were held at the 34 Avenue club in Donetsk, though they were not regular. There were also attempts to organize similar gatherings in Mariupol — a city of half a million residents — but those efforts turned out to be unsuccessful.

However, the effectiveness of such venues for meeting people was rather questionable, as Serhii from Mariupol recalls from his own experience:

“If you liked someone at a bar, you’d never actually go up and talk to them.”

“If you wanted to go to a gay club — and in Mariupol we had some attempts, but nothing came of them — you had to travel two hours to Donetsk, wait in line to get in, and yes, you could meet people there, but even that was very difficult. The culture of dating just wasn’t natural for us. Guys would just freeze — even in a gay club, where you’d think it would be easier — they couldn’t approach anyone and start talking. It was really hard. It was really scary, too”.

An excerpt from the research book Being a Lesbian in Ukraine notes that lesbian bars also poorly met the needs of the women’s community. Gradually, grassroots sports began to develop as a way for homosexual women to communicate, spend their free time, and build solidarity. Other forms of shared leisure included discussion clubs, film screenings, and creative evenings. The lesbian initiative group Rivnodennia (Equinox) from Donetsk also organized discussions, mutual support groups, and cultural events for women.

Between Cruising and Community: What Is a Men’s Pleshka?

Another form of meeting people deserves separate attention. Back in Soviet times, popular public spots for men to meet were known as pleshkas. This phenomenon persisted in independent Ukraine as well. These places were not widely known to the general public, but, as our interlocutors who grew up in those years recall, they were familiar to “those who were interested”. The character of pleshkas varied depending on their location and changed over time. Many pleshkas in both large and smaller cities could be described as cruising spots.

“Pleshkas were usually located near public restrooms. It’s horrifying to think about it now, but back then people had no choice. And yet, people existed — there were informal connections between them, contacts, and they knew, told each other where they could meet ‘their own’, in which place. It’s hard for us to imagine just how suppressed and repressed it [homosexuality] was. In every city, there were circles of acquaintances, and in every city, there was a place where one could find LGBT people”, says an advocacy expert from the “Nash Svit” (Our World) Center, describing the final Soviet years and the first years of independence.

Pleshkas were more about sex. Those who were looking for relationships usually tried to avoid such places. Even during their peak of popularity, only a small portion of gay and bisexual men actually visited pleshkas.

“If you went to a pleshka, you were signing a certain social contract. First — to be visible; second — to take a stance; third — to be ready for others to fantasize about you.”

“There was a certain sexualization in these pleshkas, which played a major role. If you wanted to be more ‘pure’ and have a higher value among those looking for something more ‘innocent’ and ‘untainted,’ then you had to avoid pleshkas”, comments Serhii K’yartan.

“There were people [among homosexuals] who had a negative attitude toward this [pleshka culture]; they tried to distance themselves from it and considered those who went there a bit reckless or like people who had nothing to lose. Being less known or less exposed was seen within the gay community as a kind of… value. So those who visited pleshkas were regarded with a bit of suspicion: ‘You’ve been to a pleshka? You’ve kind of stained yourself, gotten dirty!’ ”

It’s worth noting that visiting pleshkas could sometimes be especially dangerous.

“In the post-Soviet years, there was a phenomenon called ‘remont’ (‘repair’). Young men would gather together, go to the same pleshka to look for gay people, and beat them there. Why ‘remont’? — they thought they were ‘repairing’ society. It’s the same as what today’s aggressive homophobes believe — that they are eradicating some kind of disease that supposedly came to us from the West. Of course, that’s nonsense, because LGBTIQ+ people have always existed in every society. But in every homophobic country, it’s believed that this is some kind of nontraditional value brought from somewhere else”, recalls Andrii Kravchuk.

Where were the pleshkas located in the cities of Donetsk region?

The study “Assessment of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Kyiv and Donetsk Region” includes a list of pleshkas in the region as of 2005.

In Donetsk, the most well-known pleshka was “Nadka” (the visitors themselves would give these spots their own nicknames) — a small park and public restroom near the Shevchenko Regional Scientific Library. People would gather there in the evenings on park benches — both local youth and those who came from other cities to meet new people. Another location was a park near the old city planetarium building (165 Artema Street), which by that time had already been abandoned.

Donetsk Regional Shevchenko Library (formerly Krupskaya Library), 2010s

Other popular meeting spots for gay men in Donetsk were the “White Stones” — a section of the beach in Shcherbakov Park — and the abandoned Green Cinema located in the same park. The latter served specifically as a spot for sexual encounters.

“As evidenced by the inscriptions on the walls and our observations, practically the entire spectrum of human sexuality was represented in this place”, the study notes.

Other popular meeting spots for gay men in Donetsk were the “White Stones” — a section of the beach in Shcherbakov Park — and the abandoned Green Cinema located in the same park. The latter served specifically as a spot for sexual encounters.

“As evidenced by the inscriptions on the walls and our observations, practically the entire spectrum of human sexuality was represented in this place”, the study notes.

Remains of the Green Summer Cinema, 2008

In the satellite city of Donetsk — Makiivka — there were five active pleshkas during the same period.

The first was in the Park of the 10th Anniversary of Ukraine’s Independence (previously called the Park of the 50th Anniversary of October), and the second in Pioneer Park (now named after Dzharty). These were the two most popular spots. Makiivka men also used the city’s railway stations — the central Makiivka station and Khanzhenkove station — as meeting places for sexual encounters. Another pleshka was located in a small square near the Palace of Culture of the Pochenkova Mine.

In Horlivka, two parks — Gorky Park and Yuvileinyi Park — served as local pleshkas in that town.

In the urban space of Mariupol, there were several pleshkas. One was a small park near the Drama Theatre — though, according to research, this location had already lost its status as a pleshka by 2005, remaining popular only in earlier years. The second site was the “Arbat” alley on Engels Street, now marked on maps as the Alley of Remembrance. Another popular gay pleshka was the park of the Azovstal plant — described as a “practically deserted place.” Two public restrooms near the Primorskyi and Turyst restaurants were also known meeting points. The visitors of these locations were mostly older men aged over 40, and most pleshkas in Mariupol “operated” only during the summer and daytime hours.

A distinctive feature of Mariupol was its pleshka on the seashore — a nudist beach located between the villages of Melekyne and Rybalske.

Even the most popular pleshkas were never about large crowds or parties. The nudist beach, for example, was described like this: “Men of various ages, from 20 to 60, visit the beach, though older ones are more common. On weekends, in good weather, you can meet up to ten people here”.

For Serhii from Mariupol, the memories tied to those seaside encounters remain especially warm: “It was incredibly romantic. You’d go to the sea, find some cliff where no one’s around, sunbathe, feel the joy of life… A guy sits nearby… You swim, come back… It was really great, honestly”.

Nudist beach near Mariupol. Photo by Hanna Prokopenko

Information about other cities in the Donetsk region is not included in the mentioned study, but pleshkas still existed there — even in relatively small towns, though not in villages. These places were typically central parks or squares. In towns with railway stations, pleshkas were often located in station buildings or public toilets near the platforms, and sometimes in bus station facilities. For example, in Bakhmut, according to Yevhen Trachuk, local men used to have sex in the restroom of the railway station, where they had even built a so-called glory hole themselves. Another area for sexual encounters was a park where the lights were turned off after midnight. Dark and deserted locations at night in small towns often served as places for sexual activity “in the classic way,” as Yevhen puts it.

In the Donetsk region, pleshkas existed roughly until the early 2010s.

“For example, in 2006 you could still talk about a kind of heyday — there were cool, attractive guys there. But then, when the Internet appeared, it killed all of that”, recalls Serhii from Mariupol.

The Path to Political Activism: How the LGBTQ+ Rights Movement Developed

“We didn’t know about the rainbow flag or the LGBT acronym”

Building an LGBT rights movement in independent Ukraine had to start from scratch. Symbols that are familiar today were not widely known back then — nor were many of the terms.

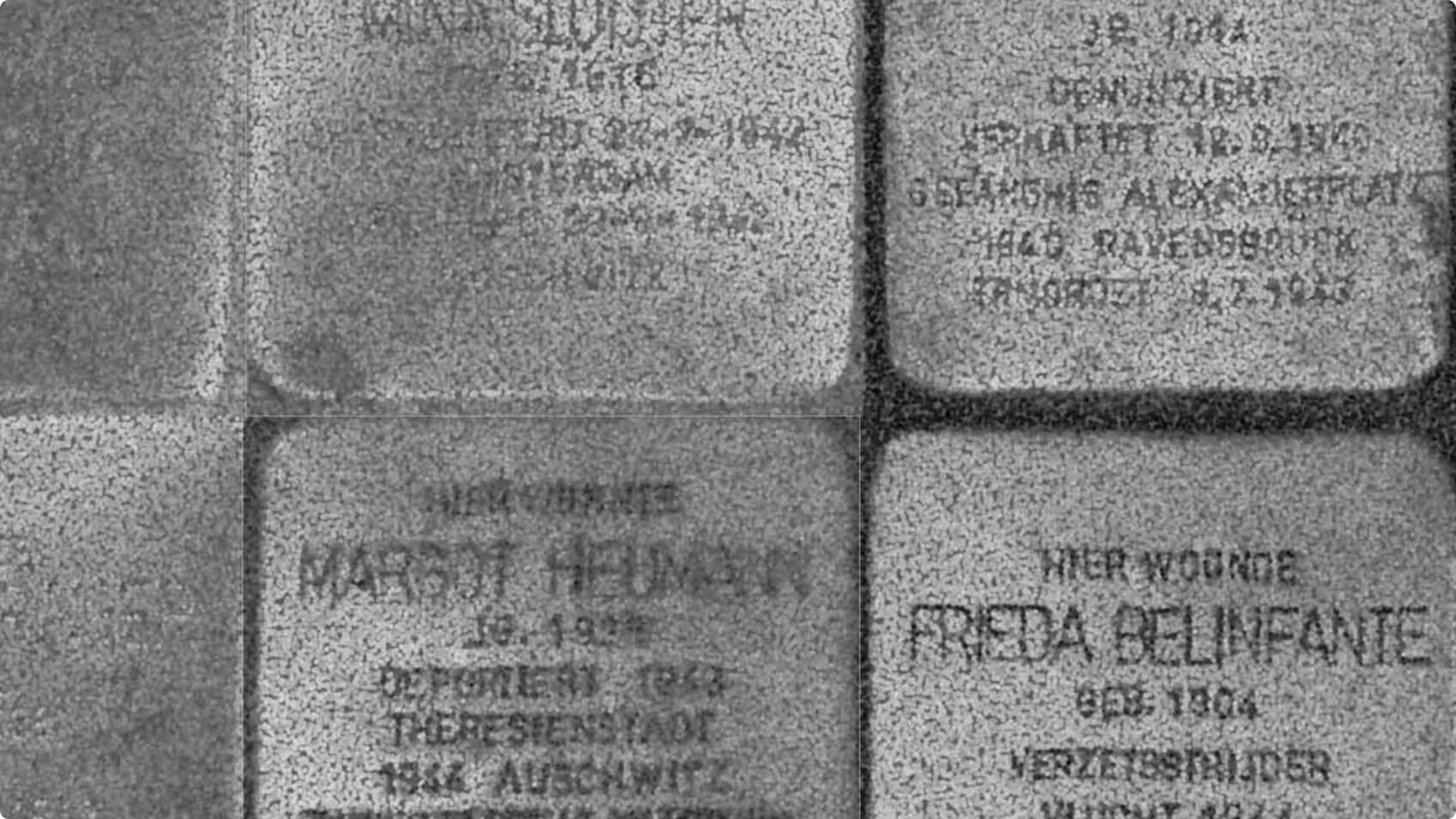

“We didn’t even know the acronym ‘LGBT’ at the time — it wasn’t common in Ukraine; it was only used abroad”, recalls Andriy, describing his path as an activist in the 1990s. He adds, “Back then, we talked about gays and lesbians; we hadn’t even heard of transgender people yet. For the first decade after Ukraine regained independence, the rainbow flag was also virtually unknown. The symbols of the LGBTQ+ rights movement — and even the words denoting these identities — gradually entered Ukrainian usage only after the 2000s. The first widely recognized symbol of the movement that we came across was the pink triangle — a marker used to identify gay men in Nazi concentration camps”.

Same-sex relationships were no longer illegal, yet they were not seen in society during the first years of independence as something natural. In particular, openly declaring one’s sexual orientation remained physically dangerous for many years.

“I don’t know if it can be called ideological violence, but violence specifically targeted at gay people has always existed”, recalls Andrii, one of our human rights activist interviewees.

Serhii from Mariupol shares another story from his city that took place around 2007–2008: “I had a friend who was a lawyer and also part of our community. He tried to open a criminal case [regarding an assault on another gay man] on the grounds of hatred based on sexual orientation. But the district police departments refused to do so. Everything was either silenced or registered as a general robbery case without any mention of the motive. The guy was beaten so badly that there wasn’t an uninjured spot left on his face. The police said it was his own fault — that he had provoked the attack with his flamboyant clothes. They didn’t even want to open the case under standard procedures for a long time. The story was never covered in the media and was never classified the way it should have been”.

“The situation started to change in the mid-2000s — roughly between 2000 and 2010. Two major things happened then. First, mass access to the internet appeared. It’s hard to imagine how much that changed things for Ukrainian LGBTIQ+ people. For us, it was a revelation. We immediately became part of the international community, and the latest trends of global movements started reaching us. Second, Ukrainian journalism began to change — the tone of publications on LGBTIQ+ topics shifted as well…” — adds Andrii.

Donetsk became the first city in Ukraine’s history where a court issued a verdict for the beating of a gay man. According to the research article “The LGBT Community of Ukraine: History and Modernity,” on November 1, 2010, the Kirovskyi District Court of Donetsk sentenced a former police officer to two years of probation — with the sentence suspended for the same term — for assaulting a local gay man, Roman Zuiev. This was the first known case of a criminal prosecution of this kind successfully won in court.

The first LGBT support centers in the Donetsk region appeared as early as the late 1990s, although their format gradually evolved over time

To fight for the rights and safety of the LGBT community, public organizations and support centers were gradually established.

“In the early years of the Ukrainian LGBTQ+ movement, it was closely connected with HIV prevention efforts”, says Andrii Kravchuk, a representative of the “Nash Svit” (Our World) Center. “Firstly, because the HIV/AIDS epidemic had just begun in Ukraine, and secondly, because that was the only sphere for many years where cooperation with the state was possible. The government encouraged initiatives to fight HIV/AIDS, so informal groups working with the LGBTQ+ community often emerged within regional and district HIV/AIDS prevention centers — and later became official NGOs”.

“The decriminalization of homosexuality was, in fact, recommended by the Ministry of Health. This was part of a standard WHO policy: if you want to effectively fight HIV/AIDS, you have to abolish criminal liability for same-sex relations. Otherwise, people simply won’t come to you, and you won’t be able to tackle this devastating disease that threatens the entire country”.

According to the Ministry of Health, since the early 1990s, Ukraine has recorded an HIV epidemic. Donetsk Oblast, in particular, held the first place in the number of diagnosed cases from 1987 to 2014. Although most infections were attributed to heterosexual contacts, at that time there was a global tendency to consider homosexual men as a high-risk group. The decriminalization of same-sex sexual activity and the emergence of organizations providing HIV testing and prevention for gay and bi men helped them avoid this risk: throughout the period until 2014, only 1.2% of men infected with HIV through sexual transmission were homosexual.

In Luhansk, as early as 1998, a regional organization called “Nash Svit” (Our World) was established, which later expanded its activities to Donetsk region. A small Donetsk team supported the operation of a community center where meetings, social gatherings, film screenings, and casual discussions took place. The center was based in and held events in Donetsk, Mariupol, and Makiivka, and in fact did not have a permanent address, “migrating” instead between various rented apartments. The branch also distributed the magazine “One of Us” in the region — one of the first magazines about and for the LGBTIQ+ community in Ukraine.

The first LGBTIQ+ organization officially registered in Donetsk was the LGBT Center “DonbassSocProject,” led by Maksym Kasyanchuk, a friend and colleague of Andriy Kravchuk:

“Maksym became fascinated with sociology, studied it, and began conducting research on attitudes toward LGBTIQ+ people in Ukraine together with professional sociologists. He registered this organization, and they focused specifically on scientific work. Not on community work, but on studying it. This was the first genuinely Donetsk-based LGBT organization, and it still exists today. The data he collected during the early years of the LGBTIQ+ movement are now invaluable”.

Already during the period of Ukraine’s first Pride attempts, in 2012, the first Diversity Forum was held in Donetsk, followed by a second forum in Mariupol in 2013. The events invited representatives of socially marginalized and vulnerable groups, civic activists, and journalists. The organization of the second forum in Mariupol was accompanied by a series of aggressive statements and actions from opponents of the LGBTIQ+ movement.

Major turning points: the Orange Revolution, the first Pride, and the beginning of the war

According to Serhii K’jartan, a favorable event that partially changed the situation for the LGBTIQ+ community in the country was the Orange Revolution. It set Ukraine on a pro-European course and reinforced the concept of human rights as a political value. After the Orange Revolution, his city began holding annual Europe Day celebrations. During these days, events were organized to introduce the people of Mariupol to the principles of democracy and European values. “Young people gathered, flags were raised, and it wasn’t about gay flags yet, but it was already about diversity; platforms appeared where different voices could be heard”, Serhii notes.

The second landmark event was the attempt to organize the first Pride in Kyiv in 2012. Although a large-scale event could not be held at that time, the very attempt sparked extensive discussions both among LGBTIQ+ activists and within the wider public. This was an achievement. Later, after the Revolution of Dignity, subsequent Pride attempts led to the LGBTIQ+ community emerging from the shadows and the movement becoming visible and public.

The Russian-Ukrainian war in 2014 radically changed the geography of LGBTIQ+ initiatives and activism in Donetsk region. According to Andriy Kravchuk, an advocacy expert at “Nash Svit” (Our World) based on observations from their center, all LGBTIQ+ activists left the occupied territories at that time.

The part of the region that remained under Ukrainian control became a refuge for initiatives that had fled the occupation and a starting point for new ones, which, after the Revolution of Dignity solidified Ukraine’s pro-European course, emerged with a new, larger wave. Even after 2022, a significant number of initiatives, once again relocated, continue to operate in Ukraine.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights

Queer in One of Most Catholic Countries in Europe: Stimulus or Hindrance?