“As a Last Resort, We Will Jump Into the River”.

How Kurdish LGBT Persons Are Fleeing To Europe via Belarus

The migration crisis in Belarus has revealed xenophobic and racist attitudes among the local population. Since 8 November, about three thousand Kurds have stayed on the Belarusian-Polish border. Many Belarusians heard about this ethnic group for the first time and sincerely do not understand why people are fleeing their homeland. Among Kurdish youth searching for a better life in Europe, there are also homosexuals who are tired of concealing their orientation. Belarusian journalist Evgenia Dolgaya who spoke to some of them explains why young Kurds are facing the perilous ordeal of going abroad.

“Tour” to Belarus

Nurjan is 23 years old. In Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, she worked as a primary school teacher. On 5 November, the young woman flew to Minsk together with her 20-year-old brother Hassan intending to reach Germany. Since their arrival, however, the brother and sister have been living with other Kurds on the Belarusian-Polish border.

“Among the residents of Iraqi Kurdistan, since the beginning of the summer there has been unceasing talk that Belarus has opened the border with Europe — allegedly Lukashenko is taking revenge for the EU sanctions. Therefore, since summer, the Kurds have already studied the local situation and posted [in social media] where to buy clothes, a tent, and where it is better to go,” Nurjan said to Zaborona.

For her and her brother, moving to Europe seemed like a real chance to get on with their lives. For years, Nurjan and Hassan’s parents feared a recurrence of the massacre of Kurds in Iraq in the 1980s, ordered by then-president Saddam Hussein. Estimates range from 50,000 to 180,000 deaths from 1987 to 1989.

The Nurjan family supported and financed the children’s relocation: the parents sold an old car and a small shop at the local market. In this way, they managed to raise $15,000. A brother and sister’s “tour” to Belarus cost two thousand dollars each. This amount included air tickets to Minsk, visa and other papers, and hotel reservations.

“We were aware that we might have to use the services of a smuggler to get us to Germany, so we thought through our options in advance. I contacted a man from Poland who successfully transported my acquaintances in the summer; we had an arrangement with him,” Nurjan explains.

Migrants in a warehouse near the border with Poland. Hrodna region, Belarus, 20 November 2021. Photo: Sefa Karacan/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

“I have tried to talk about my orientation with my mother, but it feels like she deliberately covers her ears and does not want to hear anything. There are still enough cases in Kurdistan where a girl’s family finds a groom and arranges a wedding,” she explains.

A Yazidi wedding ceremony in an IDP camp. Dahuk, Iraq, 23 January 2020. Photo: SAFIN HAMED/AFP via Getty Images

At the age of 18, Nurjan fell in love with her classmate. For two years they dated in secret, pretending to be just friends. But living in constant fear of exposure has taken its toll on the girls’ relationship. More recently, Nurjan’s former partner got married. That’s why the woman is so eager to get to Germany — she believes she will feel safe there and be able to build a safe life the way she wants.

“There is a very large diaspora of Kurds in Germany, I have been in contact with them for a long time and am friends with many of them. I see that the people who live there are different, they love whom they want, study to be someone they want, not to be someone they just have an opportunity to be. The Kurdish diaspora is very supportive of each other, so my brother and I aren’t likely to be left alone,” she says.

Who are the Kurds?

There are up to 40 million Kurds around the world, but throughout the history of the ethnic group, they have failed to create a state of their own. Today, most of the Kurdish population lives in Southwest Asia in a mountainous region called Kurdistan, which is divided between four states — Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

The aspirations of the Kurds to create their own state are feared by the authorities of these countries, as a result of which members of the population are often subjected to repressions. In Turkey, the Kurdish language was outlawed for a long time and today local authorities prohibit people from studying in it. In Iraq, Kurds account for about 17 per cent of the population. In the late 1980s, Saddam Hussein carried out a mass genocide of Kurds in Iraq. However, after his overthrow in 2003 and proclamation of a new Iraqi constitution in 2005, the Kurds have received autonomy within Iraq.

Kurdish refugees in a camp in the mountains at the Turkish-Iraqi border in April 1991. Photo: Tom Stoddart/Getty Images

“I’m not coming back”

On 8 November, a convoy of several thousand Kurds marched to the Bruzgi — Kuznica border crossing on the Belarusian-Polish border. Nurjan and her brother were among them. The main demand of the migrants was to let them into the territory of Poland so that they could reach Germany and seek asylum. The Belarusian security forces pushed the convoy into the forest so that the migrants were likely to storm the border. The Kurds set up a camp near the border fence and lived there for a week, occasionally trying to break through to Poland. However, Polish border guards pushed them back.

Polish border guards’ vehicle and an ambulance, in which doctors treat a Kurdish migrant from hypothermia. Narewka environs, Poland, 12 November 2021. Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

On the night of 15 November, rumours began to spread among migrants that people would be allowed into Germany. The information came from fake accounts in chat rooms and migrant Facebook groups. In the morning of the same day a column of Kurds marched to the border crossing point Bruzgi — Kuznica; the Belarusian law enforcement officers did not interfere. People demanded from the Polish guards to let them into Germany, but when they realized that they would not be allowed through, they put tents between the two border crossings and stayed overnight.

On the morning of 16 November, the migrants tried to force their way to the Polish side: they threw stones at Polish border guards, dismantled the iron fence, and tried to with logs. Polish border guards used tear gas and water cannons, while Belarusian law enforcers just observed and did not intervene. When the conflict subsided, some of the migrants set up a camp near the border crossing. Others went to a logistics warehouse, which the Belarusian authorities provided for their overnight stay. Nurjan and his brother also ended up in the warehouse.

“Under no pretext am I going back to Erbil. My dream of a free life is so close. I have been living in the open air for more than a week, and I will wait as long as I have to,” says Nurjan. “My brother and I have decided that, as a last resort, we will jump into the river to reach European soil. My brother, too, doesn’t want to live in a place where you have to learn to shoot and be prepared for war from birth. He is not a man of war, he wants to train as a doctor and help people.”

A Kurdish Peshmerga soldier looks at an Iraqi military position. Photo: Greg Mathieson/Mai/Getty Images

How did the migration crisis in Belarus start in the first place?

On 23 May, a Ryanair flight between Athens and Vilnius was downed in Minsk. Roman Protasevich, a Belarusian opposition activist and former editor-in-chief of the Nexta telegram channel, was on board the plane.

On the evening of 24 May, the European Union called for sanctions against Belarus: European air carriers were advised to avoid flights over Belarus, access of Belarusian airlines to the EU airspace and airports was restricted.

As soon as on 26 May, Lukashenko said at a meeting with the Belarusian parliament: “We used to stop drugs and migrants — now they will use it and catch them themselves.” After his words, the number of attempts to cross the border illegally increased. At that time migrants were mostly going to the Belarusian-Lithuanian border.

On July 2, in another speech, Lukashenko said addressing the EU: “We will no longer hold those who you have mocked in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq. We have neither the money nor the strength for that as a result of your sanctions.”

Since August 2021, the total number of registered attempts to cross the Polish, Lithuanian and Latvian borders from the territory of Belarus has reached about 40 thousand — and that doesn’t cover the successful crossings. The total number of people who died on the border, according to official data, is eight, but there are even more missing — read more about it in the Zaborona report. About three thousand people have been on the Belarusian-Polish border since 8 November.

Leave at the first opportunity

Ardalan, 25, crossed the Belarusian-Lithuanian border in early August 2021. He worked as a hairdresser in Erbil before leaving and now lives in a refugee camp in Lithuania. Ardalan is horrified to observe what is happening at the border and realizes that in some way he is lucky. He flew to Minsk from Baghdad together with his friends. The trip to his new life cost him 750 dollars — it includes a visa, tickets to Belarus and hotel accommodation.

“Living on in Erbil was impossible. Since I was a teenager I wanted to leave Kurdistan. The economic situation is getting worse and worse, but the issue is also that I am gay,” Ardalan said to Zaborona. “I realise that I would not be able to openly show my homosexuality in my homeland. True, there are people among the Kurds who are trying to fight for LGBT rights, and some manage to hide their orientation all their lives. Maybe I would put up with it, but I think it’s better to try to get to Europe first and live my life the way I want to live it.”

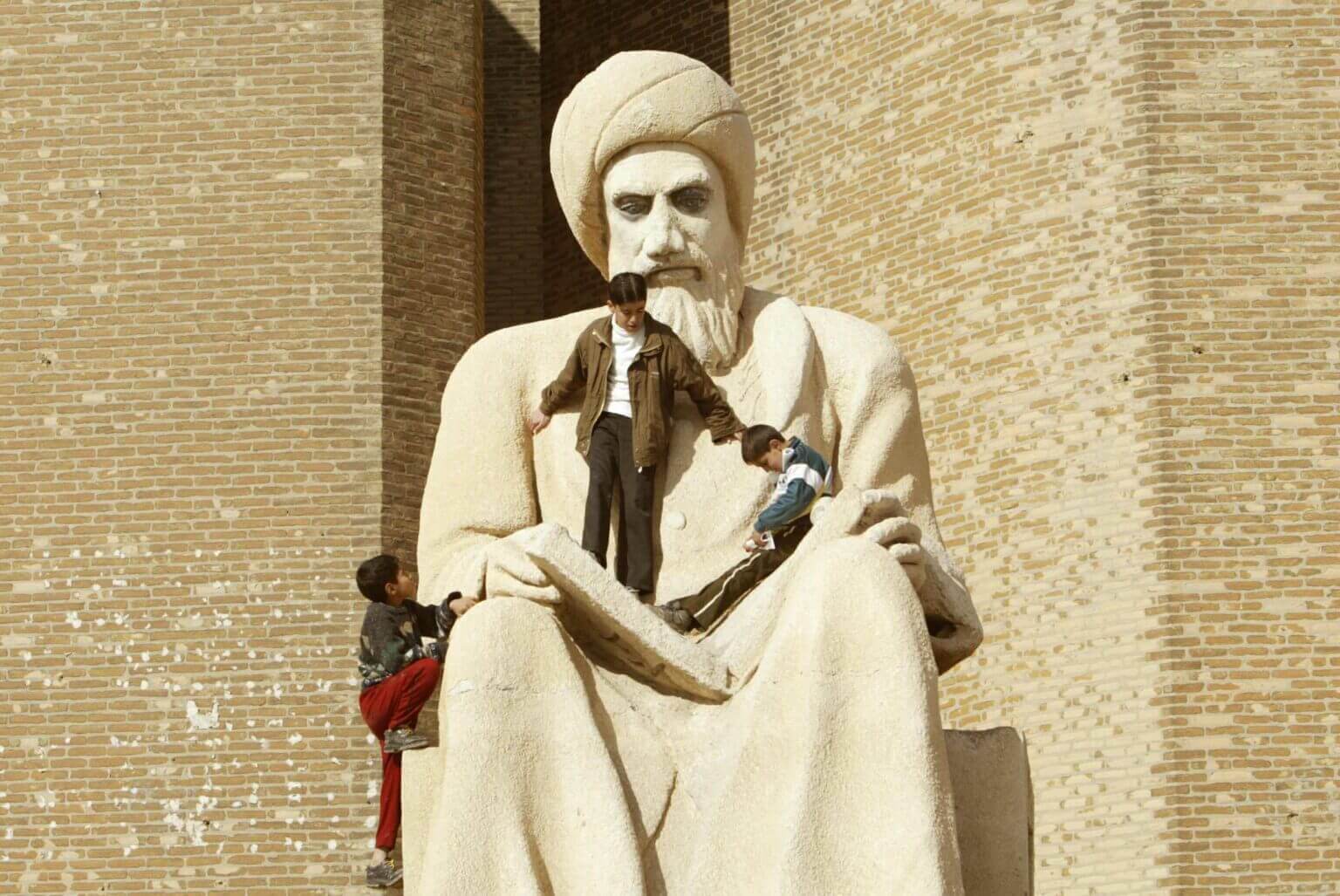

Erbil, Iraq. Photo: MUSTAFA OZER/AFP via Getty Images

Ardalan does not want to talk about his family. The young man admits that his parents are unaware of his homosexuality. Nevertheless, his desire to go to Europe has not raised any questions in his family.

“In Iraq, people live the dream of leaving. Any news about ways to cross the border goes viral. Young people are co-operating to cross the border together. It is not surprising, therefore, that young people want to leave at the first opportunity. It’s as if their desire is always in the air and everybody knows about it,” he explains.

Ardalan and his friends didn’t even stay overnight in Minsk. The first thing they did was to buy food and SIM cards and then drive straight to the Belarusian-Lithuanian border. The guy was not going to pay the smugglers. The plan was to get to Lithuania, surrender to the local border guards and apply for asylum. And so it happened: Lithuanian border guards detained the Kurds and took them to the nearest checkpoint, where they were held for 24 hours. Subsequently, the men were placed in a closed refugee camp. In September, Ardalan had an interview with a migration officer where he spoke about his homosexuality and admitted that he feared for his safety in Iraq.

“I was asked if I had received threats. I had to tell them how my openly gay Iraqi friend in Baghdad was beaten to the point of disability — his back was broken,” he recalls. “Iraqi Kurdistan is still Iraqi territory. If the Iraqi government wants to exterminate us, it will do so at any moment. And there is enough homophobia in Kurdistan itself. We don’t have a strong LGBT community that can fight for their rights. People are afraid, and I understand them: I am afraid myself.”

At the beginning of February 2022, Ardalan is to be informed about the decision concerning his refugee status. Zaborona asked what will happen if he is denied the status. “Of course, I will be upset. But I try not to see it as the end of life. I will probably try again. My dream is to live in Germany or the Netherlands. For now, I try to think of good things, I imagine learning to be a make-up artist. It helps to calm down — the camp life is psychologically difficult. But the important thing is that I am warm, unlike those Kurds who are freezing to death on the border right now.”

This article was originally published in Russian here

Nothing beats good old email

For our monthly newsletter, we pick the most important news and analysis,

and add selected content and art from queer creators.