‘The Fluidity Was F**king There’

This article was originally published in German on Blog der Republik

Identity politics has become a contested term, especially in recent years. The accusations under this catchphrase – from the liberal to right-wing political spectrum – are directed against queer identities, their self-identifications and public representations. According to these accusations, queer people deface the language, want to divide society, impose language rules and jeopardize freedom of expression. The criticism is directed against gender-inclusive language, neopronouns and queer visibility in general. It comes not only from conservatives, such as the German politician Markus Söder, but also from supposedly progressive queer people themselves. The attacks directed at trans, inter or non-binary people in particular are currently not only eroding solidarity among queer communities, but also ignoring the common history they share. If you look back into history – especially the history of lesbian places, organizations and individuals – it becomes clear how intertwined it was with that of trans and genderqueer people.

There are historically different images than the current trans hostility that permeates parts of queer and feminist movements.

Polish researcher of gender and transgender categories in historical perspective Maria Debinska states that while back then, according to Montaigne, gender could be changed by the power of one’s imagination, “Transgenderism as a deviation, disorder or disease could appear only when the transition from one sex to another was no longer conceivable.” Both the emergence of lesbian, trans and genderqueer identities thus have a common source: the binary system and the division of people into men and women on the one hand, and the separation of sexual orientation from gender identity on the other. As lesbian history scholar Marie-Jo Bonnet states, “The originality of the 19th century thus lies not in the fact that it invented a method, but that it applied it.” At the same time, the history of female and trans sexuality differed from that of male sexuality. Both have been subordinated to the interests of patriarchy and its disciplinary discourses, as described by feminist, lesbian, and transgender historians, including aforementioned Jo Bonnet, Sandy Stone or Susan Stryker.

In both Polish and German queer history, we can find many biographies depicting how women lovers, trans and gender-nonconforming people challenged prevailing norms of gender and sexuality. The purpose of this article is to explore the intersections: to consider how these identities were shaped in relation to each other, how they functioned in shared spaces, and to look at the representation of lesbianism and transgenderism in the context of solidarity.

Queer life in Poland in the 19th century and Maria Rodziewiczówna

In Poland, whose territories were located within the borders of Germany, Russia and Austria before 1914, in the 19th century queer life was shaped differently in different partitions. “Polish history, especially in 19th and 20th centuries, is extremely problematic” – says historian Joanna Ostrowska, “for example, in Poznań or not far away from Poznań they had German in their school because this was the only option, it was German partition. But on the other hand it was a perfect tool to have for a gay man or a transgender person to have an access to the whole amazing queer German Berlin or Hamburg world. And it was totally different situation as for the person born in the same year but in Warsaw, Russian partition. Another example is connected with laws. Until 1932, so not only during the partition time but also after the First World War, it was possible to be persecuted as a gay man in Warsaw, in Poznań, but for example in Kraków it was also possible to be persecuted as a queer woman, because in Kraków there was an Austrian codex there, and in Warsaw, in Poznań, Russian and Prussian. So you know what, then suddenly this Polish history starts to be really fluid, really different, you do not have one answer at the time. So this context is extremely important”.

The stories and testimonies of that time present a complex picture of the transformation of identities and social relations.

An example of a biography of a person challenging the norms of gender and sexuality is writer Maria Rodziewiczówna. Born in 1863 in the village of Pieniuha in the Russian Empire to a patriotic Polish family, she lived most of her life in the middle of a primeval forest in a manor house on the border with Belarus, which together with the surrounding nature became, as her biographer Emilia Padol writes, “the foundation of her spiritual world.” Never having married, after her fathers’ death, she took control of the Hruszowa estate, while keeping in touch with Polish literary life and gradually gaining great publicity in literary circles.

As the biographer shows, Rodziewiczówna’s highly prolific writing – nowadays associated rather with dull and moralizing patriotic bias, can read in light of her queerness. This reveals many coded tropes corresponding to her image that already challenged gender norms in the eyes of her contemporaries. “The talent is original, firm, almost masculine.” – was written about her, which led Polish queerstorians to call her – after pioneering work done by Krzysztof Tomasik – “the butch of Polish literature.” Jan Widacki, a lawyer and diplomat, an interviewee of Padol’s biographer and a descendant of Rodziewiczówna’s neighbors, recalls that “In the older generation of his family, Rodziewiczówna’s lesbianism was obvious. It was joked that she lived with her wife. With all the prudery and conservatism of the time, however, this probably did not surprise or aggravate anyone, although it was the cause of various malice and jokes.”

Rodziewiczówna loved and lived with women – first Helena Weychert, who was also described as a “male type,” and then with the gentler Jadwiga Skirmunttna. Skirmunttówna, later the author of heavily self-censored memoirs about Rodziewiczówna, described their relationship with the German word Wahlverwandtschaft (affinity by choice). For their close and affectionate relationship – they lived together and ran a farm, where Jadwiga took the position of “mistress of the house” and Rodziewiczówna took care of business – there was no word in Polish; one had to look for it in a foreign language.

The example of Rodziewiczówna perfectly illustrates the fluidity of categories concerning gender identity before the description of transgender (by Magnus Hirschfeld in 1926). Rodziewiczówna, who lived in earlier times (although she died in 1944), never defined her psychosexual identity. She may have been a heterosexual transmale, a nonbinary person or a cisgender lesbian, the biographer speculates, or, we might add, a performer of female masculine identity in the sense of Jack Halberstam: “a lively and dramatic staging of hybrid and minority genders” in the pre-lesbian and pre-trans era.

Queer subcultures and sexual sciences in Berlin during the Weimar Republic

While the gay subculture in Germany was already well-developed before the First World War, the lesbian subculture, and with it a greater scientific interest in female homosexuality and trans issues, only developed more strongly after the First World War. Weimar Berlin in particular was a forerunner of the emancipation of sexual minorities – mainly due to the activism of a German physician Magnus Hirschfeld. In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in Berlin, whose aim was to educate the public about homosexuality and mobilize against Paragraph 175. From 1871 to 1994, paragraph 175 criminalized sexual acts between persons of the male sex in Germany and was the basis for the persecution of homosexuals, including during the Nazi era. After the First World War, Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexual Science, which was not only intended to advance the scientific debate on homosexuality, but also the homosexual emancipatory movements of the time. The institute quickly became a focal point for many queer people and different identities. While the institute initially focused on the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, it gradually became more concerned with sexual education and supporting political and individual concerns. Hirschfeld was one of the few scientists who also focused on intersex and trans issues. The institute issued the first supplementary identity cards, known as transvestite license (german: Transvestitenschein), for trans people. These allowed them to wear clothing that matched their gender identity. One of the first gender reassignment operations was also carried out on the Danish painter Lili Elbe, with the help of the institute. However, one must note that although Hirschfeld did important and fundamental work for queer people, his scientific theories were also strongly characterized by biologism and eugenics.

Lotte Hahm, the Violetta Damenklub and Die Freundin

While science played an important role in the formation and development of homosexual identities during this period, in addition to the development of medical knowledge about non-heteronormativity there appeared numerous associations, meeting spaces were created, as well as diverse media aimed exclusively at the non-heteronormative community, and this process was further enhanced by the development of mass popular culture. Within these circles, women created their own visible subculture: in Berlin alone, there were nearly 50 clubs and bars exclusively for non-heteronormative women, designed for regulars of varying social and material status.

Part of the growing queer subculture in Berlin after the First World War was lesbian activist Lotte Hahm. Her commitment was of great importance for both lesbian and trans communities. In 1926, she founded Violetta Damenklub (Violettas Ladies’ Club), which quickly became an important centre of Berlin’s lesbian subculture. The Damenklub – the German terms Dame and Freundin were common codes for lesbian at the time – was not only a place for pleasure, but also for networking and political mobilization. Lotte Hahm tried to build up a larger support network early on. She established a contact exchange, helped to found new groups for lesbians and trans people throughout Germany (the term transvestites was used at the time), contributed to magazines and created jobs. In addition to the Violetta Damenklub, she founded several other bars – some of them together with her partner Käthe Fleischmann – such as the Monokel-Bude and the Manuela-Bar. The program of the clubs was not only aimed at lesbian women but also included so-called transvestite evenings. The mobilization and networking of trans people was an important concern for Lotte Hahm. Her activism probably encouraged the founding of the D’Eon association for transvestites at the Berlin Institute for Sexual Science in 1930.

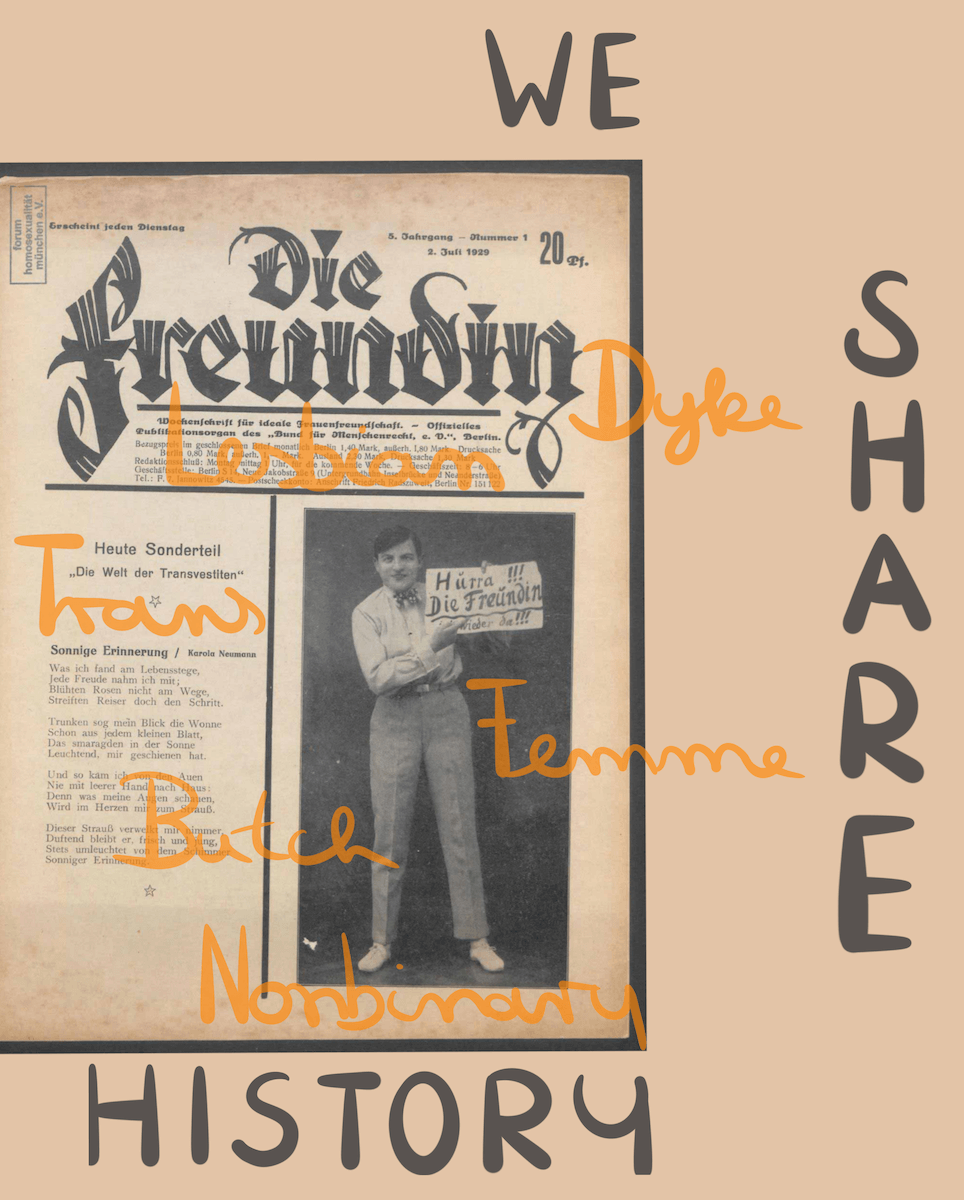

Illustration Jona Wendel, Die Freundin 1929 – Issue 1, Archive of the Forum Queeres Archiv München

A path to social activism and collective identity-building was also offered to women and non-heteronormative people by the high-volume magazine Die Freundin, which was published from 1924 to 1933 (first monthly, then weekly) and was closely associated with the League for Human Rights. There were also regular supplements or special sections, which primarily dealt with trans issues and served to promote understanding between different queer positions and identities. For example, a reader who called herself ‘Ca, a sister on the western border of the Reich’ wrote in a 1929 issue:

‘And it is precisely tolerance that must characterize us if we demand that people also be tolerant towards us. That is the aim of our struggle and the purpose of our union, that we too are granted a place in the sun, that we are given the right to live according to our Creator-given nature without being ostracized by society and the police. Are we not human beings too? Or has the Lord made us his ‘journeyman’s piece’? Doesn’t it mean despising the entire female gender if we, who are women inside (albeit in a false guise), are categorized as inferior?’

These words not only reveal a desire for mutual understanding and tolerance, but also contemporary notions of trans or genderqueer identities.

Asked about the differences between queer scenes in pre-war Poland and Germany, historian Joanna Ostrowska says:

“The main difference which I see connected with Germany and Poland, and this is not only before the war, also the whole 20th century, the queer history of Poland is, to be honest, the history of pleasure. So, it was not about creating an organization, it was all about being together. It was about sex, having fun, partying. Undercover of course.”

It was extremely sexy. It was different to Germany where it was more like: okay let’s have sex and a bit of fun but then let’s found an organization or establish some kind of newspaper.

Sexual inversion

The theory of sexual inversion was not only a common theory in the sex sciences but was also personally expressed and recognized by many queer people. It describes people whose perception of their internal sex does not match external sexual characteristics and that there is an innate sexual inversion. Men were assumed to have a female inner sex and women a male inner sex. This was often linked to a male or female soul. However, scientists and queer people used this theory to explain not only trans identities, but also sexual orientations. Lesbian or gay inverts were therefore sometimes labelled as latently heterosexual in the course of this theory, as sexuality was only reversed due to the deviation of internal and external gender perception. Lesbian women were often also referred to as contrasexual women. The sexual desire of other women, the desire for education, political participation or physical activity was associated with a male gender character or a male soul.

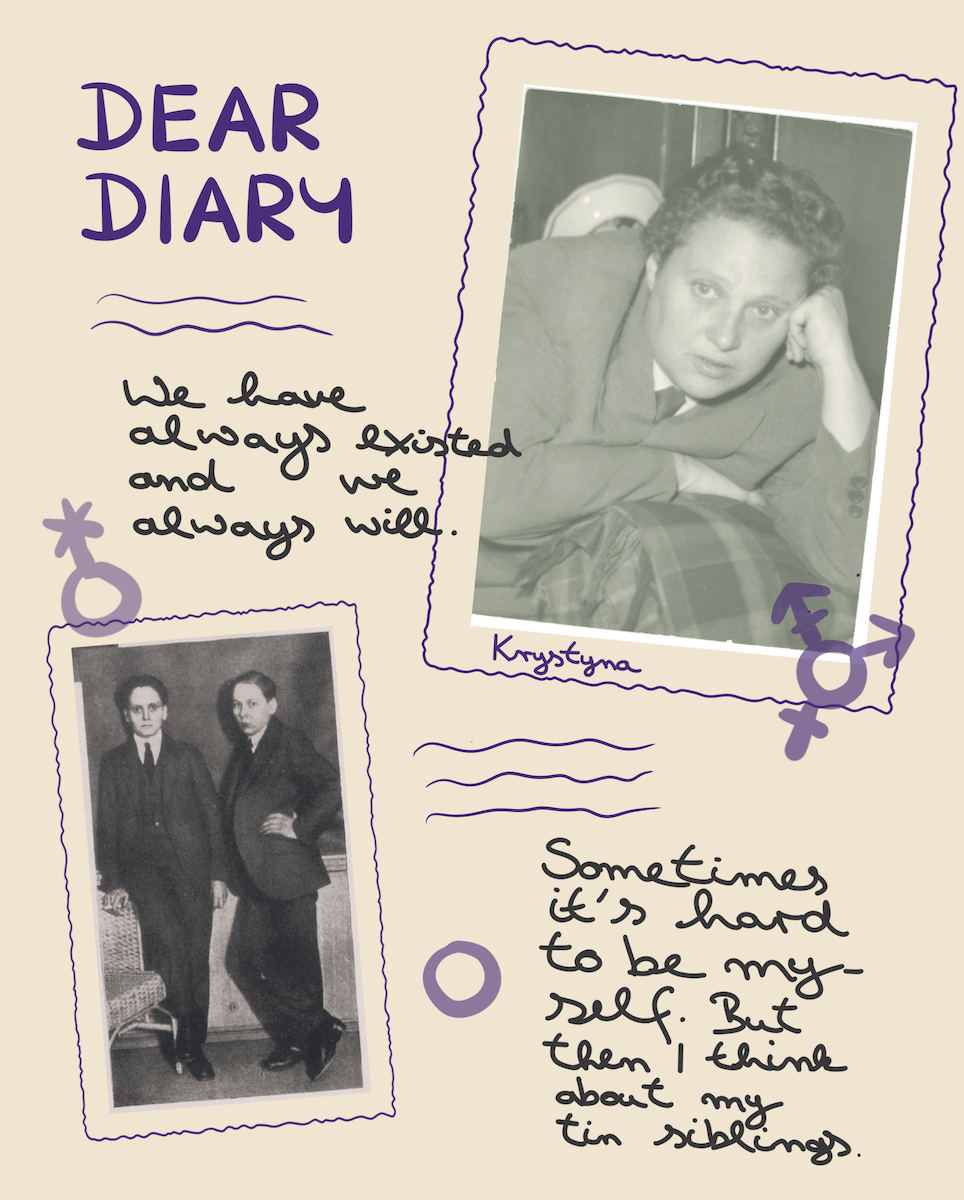

There are many queer people in history who expressed a similar understanding of their own queerness – Anne Lister, Radclyffe Hall, Gertrude Stein and possibly also Lotte Hahm. For many, this self-perception was accompanied by experimentation with gender expression, gender roles and dress and hairstyle codes. It illustrates that different gender identities, sexual orientations and individual gender expression were sometimes thought of together and in their intersection. However, while academia remained in a strictly binary gender mindset, queer people themselves often described their identity or sexual orientation as much more fluid. Historian Joanna Ostrowska who has researched many queer biographies and written books about the persecution of queer people by the Nazis states, “What I can say is that the fluidity was the most important for a lot of the protagonists I have researched. Yes, sometimes they didn’t have the power or energy, or they didn’t want to express themselves using one label or they used for example the label homosexual because this was the only label they knew. But there’s many sources – by themselves, not perpetrators – where they expressed their identity in a fluid way. Like switching their pronouns when writing about themselves in a diary.”

One of Joanna Ostrowska’s historical protagonists who has also written about their fluid gender identity is Krystyna. “Krystyna has written 27 books. It’s crazy. I have so many examples. I have never had the situation that I have so much about somebody’s identity, not only gender identity. Sometimes she would use male pronouns and a male nickname and sometimes she pronouns. And until the end she used Krystyna as her name. You know, the fluidity was fucking there.”

Illustration: Jona Wendel, top right: Krystyna Modrzewska, photograph [1940s], Photography Archive of the ‘Brama Grodzka – Teatr NN’ Centre in Lublin, bottom left: Gert Liehr and his uncle _Gehse. Magnus Hirschfeld Society Berlin, Magnus Hirschfeld, Sex Education. Image section, p. 326, © qualitatively revised by Clara Hartmann.

First gender-affirming surgery in Poland

The first gender-affirming surgery performed in Poland was in 1937. A trans athlete Witold Smetek (1910-1983) underwent it in the gynecology department in Warsaw. After the war, the first surgery was performed in 1963 in the urology department at the Kolejowy Hospital in Międzylesie, Warsaw – this was also the first known medical transition of a woman in Poland. Nevertheless, transgenderism in Poland only began to be discussed more widely in the late 1980s, with the lifting of the pink curtain, when the first activists and doctors began to spread Western sexological knowledge – the former in the form of zines, the latter in medical practice. It was then that the book “Apocalypse of Sex” was published in Poland by two sexologists: Stanislaw Dulko and Kazimierz Imielinski, based on the testimonies of anonymous trans people.

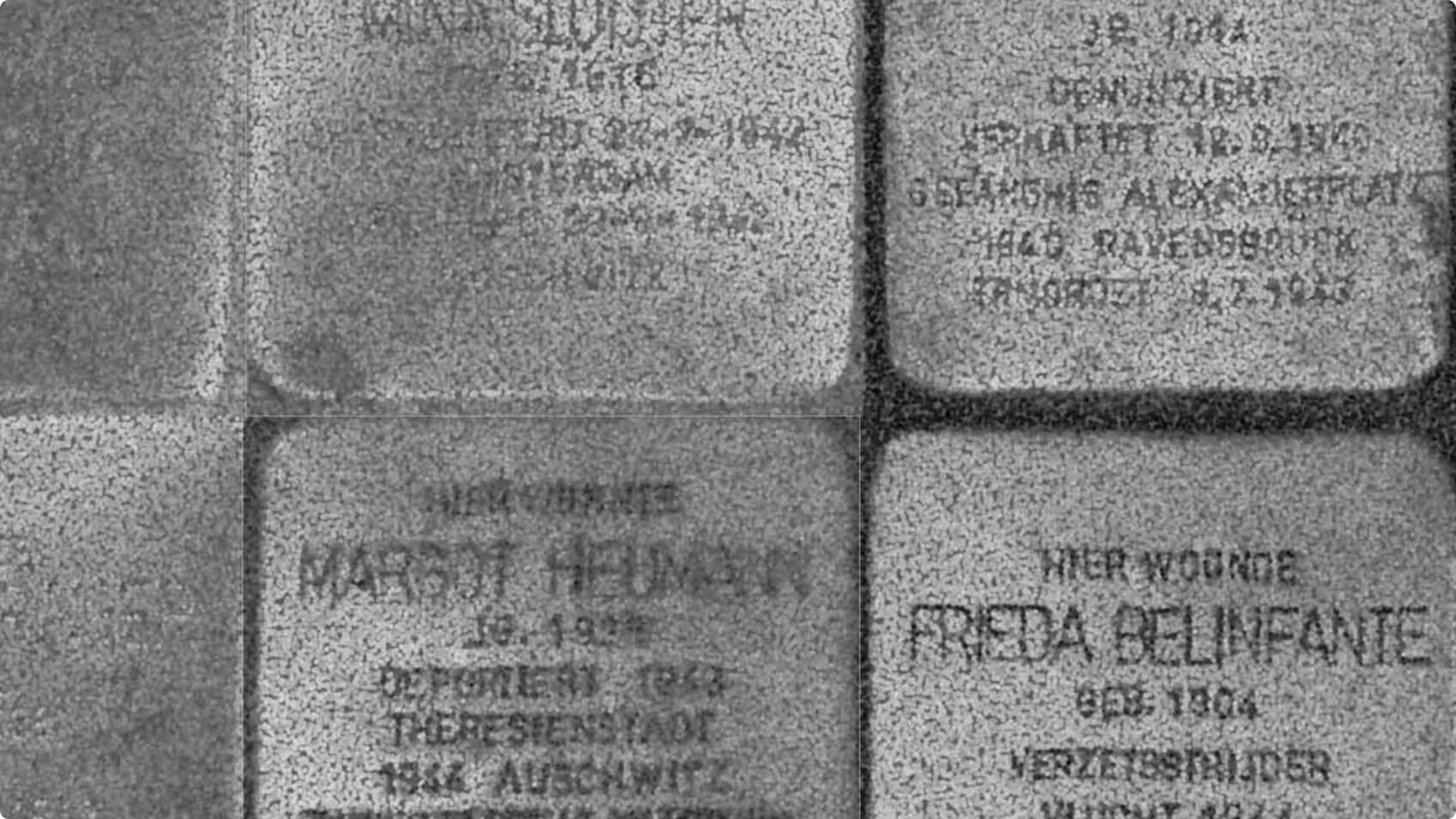

The rise of the NSDAP and persecution of queer people in Nazi Germany

Immediately after the political transfer of power to the NSDAP in 1933, the National Socialists smashed the queer subculture of the Weimar Republic. The Institute for Sexual Research, founded by Magnus Hirschfeld, was raided, its archives destroyed, and its books burned. Since its founding in 1919, the Institute’s work had made a significant contribution to increasing tolerance of homosexuality and trans identity. Under the Nazis, the regulations regarding the Transvestitenschein varied. Some people had their transvestite license revoked, others were not issued new ones and in some places they were extended. This shows how differently trans people experienced the Nazi era in Germany and how much they were dependent on the favor of the people around them.

Hertha Wind was born in 1897 in Ludwigshafen, Germany. It was only after serving in the navy during the First World War, getting married and having two sons that she was able to accept her trans identity. In 1930 she went to see Magnus Hirschfeld, who helped her and referred her to doctors. In 1931 she underwent her first sex change operation in Frankfurt. In the summer of 1933, she was committed to a psychiatric hospital for a year and forced to live as a man. After her release, she underwent further operations in Germany in 1939 and 1940. She died in poverty at the age of 75 in Mannheim.

However, there were also trans people who were more affected by Nazi persecution. Some were deported to concentration camps, for example under Paragraph 175, or as so-called asocials or professional criminals. In Hamburg in 1933, police authorities were ordered “to pay special attention to transvestites and, if necessary, transfer them to the concentration camp”. Liddy Bacroff, who described herself as a “transvestite”, earned her living as a sex worker, was sentenced there in the summer of 1938 for “commercial unnatural fornication.” After serving her sentence in a men’s prison, she was sent to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, where she was murdered on January 6, 1943, at the age of 34.

Categories and labels in historical research

It is only in recent years that historical research has made an effort to portray the lives of people who did not conform to the heterosexual norm and gender binary during the Nazi era. Historian Joanna Ostrowska says that there is an “ocean of sources” that has not yet been explored. She herself has found it difficult to look at these biographies in retrospect using our current categories and queer labels:

“What I learned is that the safest way not to harm protagonists is by not using any labels. As a historian it is my responsibility not to harm people by putting labels on to them. I always try to find sources by them, not only perpetrators. And sometimes I need a lot of time to catch what’s going on there. And I’m talking about sexual orientation, I’m talking about gender identity, but I’m talking also talking about other categories. I’m talking about nationality, about class, all of that.”

The word lesbian has only been used in Germany since the 1960s. This makes the search for sources on queer lives more difficult for researchers.

Women who loved women were not persecuted under Paragraph 175 in Germany, but they were in Austria. This meant that some lesbian women survived the Third Reich unharmed. This was made easier by the fact that many men were at the front and the role of women in general was changing. An example: two mothers with small children move in together to share the care work so that they can take turns working while their husbands are at war. Perhaps this was a necessity of the time or an expression of lesbian love and cohabitation. For this reason, it is very difficult for historians to make accurate statements about lesbian women in the Nazi era in retrospect, unless one is lucky enough to find testimonies that are informative and address the issues in concrete terms.

Käthe Lowenthal

Nevertheless, lesbian women had to fear state repression. They were persecuted as so-called “Asoziale”, or because they were Sinti or Roma or Jewish, like the painter Käthe Lowenthal. She was born into a Jewish family in Berlin in 1878. She converted to Christianity as a teenager. She studied at various private art schools and met the painter Erna Raabe at the age of 24. She returned from a stay in Switzerland in 1935 to care for her seriously ill friend. Erna Raabe died in 1938, and Käthe Lowenthal was deported to the Izbica camp in Poland and murdered in 1942 because she was Jewish.

Lesbians in post-war Germany and the New Women’s Movement

The post-war period in Germany is characterized by the fact that sexuality, especially lesbian love, was no longer talked about. This changed with the women’s movement in the late 1960s, in which many lesbians played a very active role.

In the course of the New Women’s Movement of the 1970s and 1980s, a strong collective lesbian identity and culture emerged in West Germany. As in the pre-war period, lesbianism was ascribed a political dimension and seen as resistance, sometimes even as a solution against patriarchal oppression. One of the first lesbian groups to be founded as part of the New Women’s Movement was the Homosexual Women’s Action Cologne (HFA) in 1972. Shortly afterwards, after a screening of the film Not the Homosexual is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives by Rosa von Praunheim, the Homosexual Action West Berlin Women’s Group (HAW) was founded. They described themselves as gay women (in German: schwule Frauen), organized protest actions and showed solidarity with the struggles of the women’s movement.

Hardly any lesbians in the GDR?

While women-loving women in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) were increasingly confident in calling themselves lesbians and gay women, the situation in East Germany and the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was different. Historians such as Ulrike Froböse assume that the lesbian “we-identity” developed less in the GDR, although women in the GDR were more emancipated in many areas than in the FRG. This was mainly due to the fact that the individual identities of women and men were formed within the collective socialist identity. It was both more difficult for them to find their individual identities as lesbian women and to network and come together as lesbians. This and the fear of repression meant that few women-loving women openly described themselves as lesbians in the GDR. The first independent lesbian group in the GDR was Lesbians in the Church, which was formed in 1982. Here too, the group defined itself primarily through its joint political work against discrimination against sexual minorities. This was part of the reason why its members were monitored by the Stasi.

As there were no public queer meeting places, many met in private apartments for parties, cultural programs or political exchange.

One of these party apartments belonged to Rita “Tommy” Thomas. Tommy stood out even in their youth due to their androgynous style of dress and general non-conformity. Tommy was also always very open about their love for women and lived with their partner Helli from 1950 until their death. In the 1970s, Tommy became a member of the Homosexual Interest Group Berlin (HIB), the first association of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and trans people in East Berlin.

Being trans in the GDR

The visibility of trans people in the GDR was even more restricted than the visibility of lesbians. Although a “decree on the gender reassignment of transsexuals” was issued in the GDR four years before the “Transsexuals Act” in the FRG in 1980, it was not published and was therefore not known to the general public.

Illustration: Jona Wendel, photograph: Petra Gall, Karamba SchlosserinnenKollektiv 1985 K1 N1, Schwules Museum Berlin, inventory number: F-NL-PGA-2-613

Writer Jayne-Ann Igel grew up in the GDR and only found out about the decree in 1989. As a trans woman, she had no concept of her identity for a long time and no opportunities to exchange ideas with others. It wasn’t until the fall of the Berlin Wall that many trans people in Germany had the opportunity to exchange and connect. As a result, not only the exchange between trans or genderqueer people was severely restricted for decades, but also between queer people with different identities in general, i.e. trans and lesbian people.

Lesbian representation and queer solidarity today

The lesbian scene today consists of many different bubbles. On the one hand, there is growing acceptance thanks to television formats such as the lesbian dating show “Princess Charming” and the fact that many players on the national football team have come out. On the other hand, the social shift to the right is also reflected in the fact that participants in CDSs have been attacked more frequently in recent years.

Bela is working for the project 100% Mensch. She tells us about the Utopia Kiosk in Stuttgart, which serves as a queer venue. Bela observes that people show up there “who don’t feel comfortable in the other queer spaces and bars”. This is because they are “often very gay, white, male-dominated. Not all gay men are willing to share their privileges. The same goes for lesbian women who do not want to open their spaces to trans people.

As far as the mainstream queer community is concerned, Bela perceives that there is “still very little awareness of intersectional feminism”. Bela sees this as problematic because this anti-trans movement “has also been able to gain a lot of influence in politics. She cites a recent example. In January, the „Gewalthilfegesetz” (Violence Assistance Act) was ratified in Germany. This means, for example, that women’s shelters and counseling centers will receive more funding. But the law explicitly excludes trans, inter and non-binary people.

To fight structural discrimination like this but also the rise of transphobia worldwide it is important to strengthen the solidarity between queer communities. Even though conflicts within queer communities have always existed so have strong solidarity and shared experiences and spaces. And maybe with more focus on the history of lesbian, trans and gender-nonconforming people, bonds and solidarity will grow stronger again.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQI Ukrainian Refugees

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani and Sinti Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights

Queer in One of Most Catholic Countries in Europe: Stimulus or Hindrance?