Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

This article was originally published in German on taz

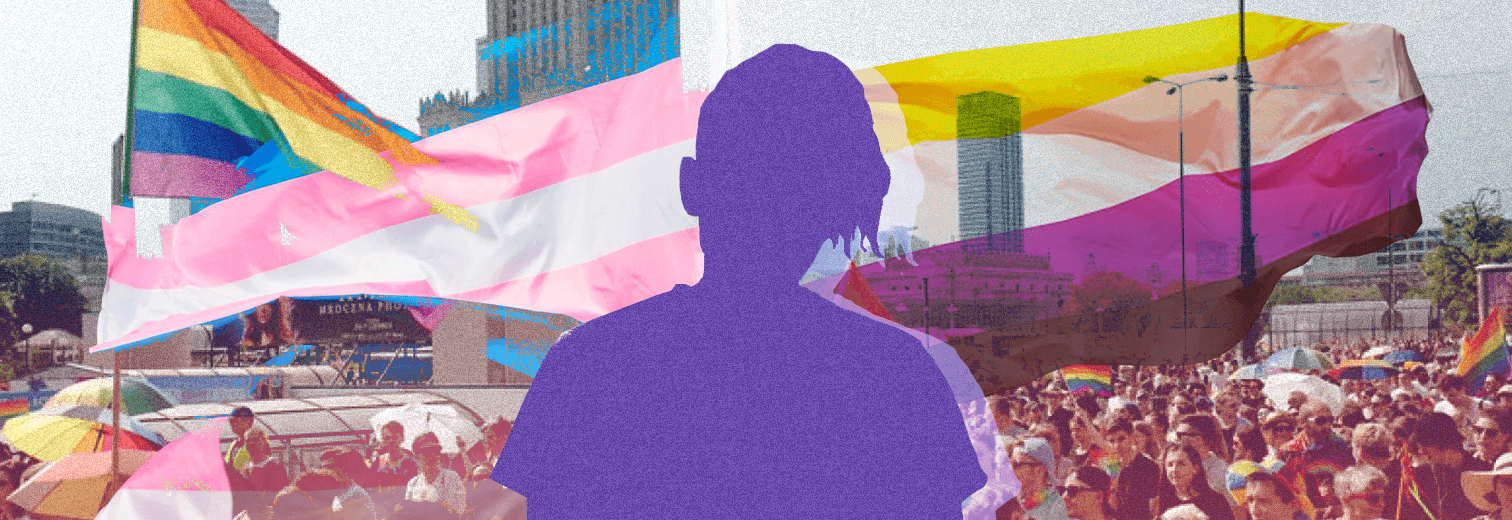

Symbol of self-determination: the trans flag. Many trans and non-binary people experience discrimination and violence.

Photo: Terrence Jennings/Redux/laif

First, Kari had to hand over her cell phone. Then a staff member rummaged through both of her bags. She took away Kari’s hormones and medications. And all items that, according to the staff member, were not suitable for a woman. Intrusive enough – even if Kari were a woman. Kari is trans and non-binary. And Kari experienced violence in a situation where Kari was promised protection. The phenomenon of people being subjected to queerphobic violence under the guise of help or counseling is hardly documented. It has a long history that continues to the present day, a history of oppression and masking, of abused science, but also of resistance and self-assertion.

For Kari, it happened like this: Kari lived with violence for years. Because the perpetrators would look for Kari after she fled, Kari needed a safe place to stay. Kari therefore called several counseling centers, but they refused to provide protection. The rejection was always the same: the rooms were only available to cis women. That was about five years ago. Kari was in her early 20s at the time.

A small Christian organization finally took Kari in. Kari recounts what happened next on an afternoon in September – in a quiet room in a place that cannot be named. The risk of revealing Kari’s whereabouts is too great. The hormones and medication prevented a relationship with God, the staff at the shelter said. And God was a prerequisite for healing. However, they understood “healing” differently than Kari.

The first step was to “admit” that she was a woman. Kari also had to become heterosexual and conform to the required gender role in every respect. Wear dresses, nail polish, makeup. She was not allowed to sing in a deep voice or repair bicycles. Only then would Kari be freed from “sin,” and only then would the chronic illnesses and traumas disappear. Then Kari would no longer experience violence. It was only with the help of another counseling center for victims of violence that Kari was able to move, after two years in various apartments run by small Christian organizations, to a place where the goal was actually to keep Kari safe. Where the focus was no longer on attacking Kari.

Conversion attempts are difficult to recognize

Kari’s real name is different, and many details of this story remain unpublished. The editors of taz have documents that substantiate the key points of Kari’s story. The employee of the counseling center for victims of violence who helped Kari escape from the Christian organizations has confirmed Kari’s experiences. Individual statements cannot be verified, but what Kari recounts is similar to other reports from survivors of so-called conversion treatments.

These include practices intended to change or suppress a person’s gender identity or sexual orientation. Those affected experience conversion attempts at school, in their families, in clinics, in psychotherapy, or in Christian communities. They range from psychological and physical to ritualistic methods. However, they are usually difficult to recognize.

The counseling center “Liebesleben” provides information on this topic. Conversion attempts are hidden behind other terms, such as “reintegrative” or ‘“reparative” therapy, and are disguised as offers of help. “In most cases, the initial focus is not on gender identity or sexual orientation, but on how to become happy,” writes a spokesperson for the Federal Institute for Public Health, which is responsible for the counseling center, in response to a request from the taz newspaper. “In the course of conversations, however, it is then conveyed that homosexuality, asexuality, bi- and pansexuality, but also trans*, non-binary* and inter* identities are wrong – and that you can only be happy as a heterosexual or cis* person.”

In Germany, conversion treatments have been banned since 2020 if they are performed on minors or against the will of those affected.

But how do you prove coercion when it is disguised as help? The dangerous consequences of conversion attempts, on the other hand, are easy to prove. They can be triggers for depression and suicide – and they fuel discrimination. The “Liebesleben” counseling center received 681 inquiries in 2024 alone. This represents a significant increase since the counseling center opened in 2021, writes the spokeswoman.

The staff at the facilities pressured Kari with religious rites. Kari is not Christian. And Kari is stubborn. “I consistently said that I don’t believe in the Holy Spirit,” says Kari. The employees then changed their tactics, attempting to alter Kari’s identity with pseudo-therapeutic methods, meditation, and physical exercises. “Like this,” says Kari, crossing her wrists in front of her upper body and drumming her fingertips on her chest: “That was supposed to exorcise the devil from me.”

Memorial stone in Buchenwald for persecuted homosexuals

Photo: H.G. Vorndran/Zoonar/imago

But apparently, calling on God was not enough. The assaults were also physical, says Kari. The staff took advantage of her flashbacks. When pain and cramps paralyzed Kari, they laid their hands on Kari’s body in prayer. The employees urged Kari to see a surgeon.

The surgeon was supposed to surgically reverse the gender reassignment procedures that Kari had undergone earlier. Kari refused. Kari knew all along that this was not about helping her. “They tried to change me. They just didn’t believe in my gender.” Even in retrospect, it is not easy to find the words to describe what Kari experienced. Some of the interventions in Kari’s self-determination were too subtle, others too absurd.

For Kari, identity was never in doubt

Reporting it to the police? Out of many reasons, that is out of the question. For one thing, Kari lacks the certainty that police officers—and, should the case go to court, judges—are sensitive to queerphobic violence. Kari fears being misgendered in court and exposed to transphobic stereotypes. This would be an additional burden in a situation that already requires a difficult—and public—confrontation. And even if Kari were to win in court, the institution would only face a fine. Would that really change anything? Would it cost the operator its operating license? Kari does not believe in punishment. “They would see it more as an attack by the devil than as a reason to rethink their way of working,” says Kari.

What was ultimately crucial for Kari’s survival was that for Kari, identity was never in doubt. “I knew that I could feel differently,” says Kari. “It was more important to me to live honestly, even if it had negative consequences, than to pretend to be something I’m not.” Even though it took a lot of strength, Kari managed to take some of the power away from the staff with moments of resistance.

Such resistance could take the form of going to the public bookcase and secretly swapping Bibles from the shelter for secular literature; discussing the gender of fabric with employees in the shopping center while buying clothes; singing supposedly pagan songs during prayer sessions; saying “Gaymen” loudly instead of ‘Amen’ at the end of prayers. In her head, she would sing the chorus of “Take Me to Church” by Hozier—a song about love and church hypocrisy.

What Kari experienced is not an isolated case—nor is it a new invention. The claim that queer people can be “cured” has a long history. As early as the end of the 19th century, medicine developed the idea of changing people’s gender identity or sexual orientation. This tied in with Christian stigmatization and legal punishment. Medical historian Rainer Herrn researches how gender and sexual diversity is dealt with.

“Medicine followed in the footsteps of religion, so to speak, and the phenomenon went from being a sin to a crime to a disease,” he says in an interview with taz.

At that time, “contrary sexual feelings” included all sexualities and genders that did not conform to the heterosexual two-gender norm. Researchers argued about whether their origin was innate or acquired. In the end, both assumptions were used against those affected. Whether with hypnosis, hormones, or castration, the interest was political. Medical research served as a stepping stone, says Herrn. “Medicine, the police, and the judiciary are equally helpful in maintaining order here.”

Progressive-minded scientists of their time, such as Magnus Hirschfeld, supported the “innate” thesis. In the fight against the criminalization of homosexuality, he provided evidence that it was neither treatable nor punishable.

The National Socialists weaponized this logic: they declared queer life a “threat to the people,” thereby legitimizing attempts at conversion, persecution, and extermination. The gender order remained a state priority: from 1936 onwards, the notorious “pink lists” were compiled in the police department “Reich Central Office for Combating Homosexuality and Abortion,” registers that enabled targeted persecution. Between 1933 and 1945, around 63,000 people were convicted as gay men under Section 175 of the Reich Penal Code. Many of them were subjected to experiments in concentration camps.

Bundestag, 2023: Klaus Schirdewahn commemorates queer victims of National Socialism

Photo: Christian Ditsch/imago

Experiments in “reorientation” took place in Buchenwald

Today, the former “Block 50” at the Buchenwald Memorial reminds us of how National Socialism misused science as a pretext for medical violence. Its foundation is lined with red bricks, and it stands out somewhat among the other barracks ruins on the dome of the Ettenberg. A sharp wind blows across the grounds, as it often does at this time of year, at the end of September. During the concentration camp era, this was where the scientists’ offices were located; they produced vaccines, for example against typhus.

Michael Löffelsender heads the memorial’s historical department. During a tour, he explains that medical experiments were carried out on prisoners here between 1941 and 1945, including attempts at surgical “reorientation” in 1944. For Löffelsender, “Block 50” symbolizes the cooperation between medicine and National Socialism: “The camp attracted people who were willing to experiment on humans.”

Homophobia and transphobia were not unique to the Nazi regime. But it provided the “disposable human mass,” says Löffelsender. In “Block 46,” the infirmary, they tested vaccines on humans, and it was probably here that the experiments of Danish physician Carl Vaernet took place. Already controversial at the time, he claimed to be able to “treat” homosexuality. He implanted testosterone glands in the groin of up to twenty prisoners; several did not survive the procedure.

The persecution did not end with the war. After liberation, the government of the new Federal Republic did not seek to recognize queer life; on the contrary. Until 1969, the judiciary convicted around 50,000 people under Paragraph 175, which remained in force, and many more were investigated. The “pink lists” continued to exist, and it was not until 1994 that the paragraph was repealed. The Federal Republic, writes the Association Queer Diversity (LSVD), “deliberately sought healing from the horrors of National Socialism in Christian morality.” For those persecuted, this meant that oppression continued—now in a Christian-nationalist guise.

One of those convicted was Klaus Schirdewahn. He was 17 years old when he was “caught” by the police with another man in a public toilet. That was in 1964. Now 78, he recounts the story to taz in a video interview. Because he was a minor at the time of his conviction, the court offered him the option of undergoing “voluntary” behavioral therapy instead of a prison sentence. “When I heard that the other guy had to go to prison, my heart sank into my pocket,” he says. To this day, he does not know what became of the other man. He pauses briefly: “Nevertheless, I was glad that for me it only meant therapy.” His parents were strict Christians and, in their view, their son had committed a mortal sin. He was forced not to talk to anyone about it.

Only friendly feelings towards other men

The therapist told him: “Every young man goes through this phase.” And that it would pass as soon as the “right woman came along.” A “real man” should only have friendly feelings toward other men. Schirdewahn was told to stay away from relevant bars and to stop going to the swimming pool, where, he had confessed, he had romantic encounters. The therapist justified the treatment on the grounds of “public health”: A “normal” family was important, but his sexuality was forbidden, a disease that could be “cured.”

Bautzen, August 2025: Right-wingers still openly display their hostility toward queer people

Photo: Christian Mang/reuters

As part of the treatment, Schirdewahn was supposed to paint pictures. “I thought it was funny,” he says. So he painted trees, forest paths, the sky. He had to take the so-called Rorschach test, in which patients are asked to interpret inkblots. “I found that particularly clever, because sometimes I saw things I would rather not have seen,” says Schirdwahn. He grins and shrugs his shoulders. “Of course, those were signs that I wasn’t on the right track yet.”

He says he fibbed to get through the sessions. For example, when the therapist asked him when he last thought about a boy or whether he had met up with one. “I kept that to myself,” says Schirdewahn. His desires never changed. Nevertheless, after two years, Schirdewahn believed he was cured. The then 19-year-old met a woman in the youth group of his Protestant church. He was able to talk to her – for the first time about his feelings, his conviction, and the therapy. They had a romantic relationship, says Schirdewahn, when he thinks back on it. Just one without sexuality. That wasn’t an option for either of them before marriage anyway.

They got engaged at the end of 1966. “I told the doctor about it. He was happy that his therapy had worked. And I was happy that the verdict was final.” Today, Schirdwahn says he was not “cured.” Today, he uses a different term for it: brainwashing.

The effect did not last long. After a few weeks, Schirdewahn had a “relapse.” — that’s what he still calls his first encounter with a man after therapy. He doesn’t regret following his feelings. But at the time, he had a nervous breakdown: “It came on so suddenly that no doctor knew what was wrong with me. I had a fever for three weeks and was completely exhausted.” It was probably feelings of guilt — an echo of the brainwashing.

Now, he only feels guilty towards his former wife and their daughter. In 1980, he left her and moved in with his partner. But it wasn’t until decades later that he spoke publicly for the first time about his conviction and the “therapy,” first at an exhibition in 2015, then in the Bundestag in 2018. A year earlier, his conviction under Paragraph 175 had been overturned. Schirdewahn received 3,000 euros in compensation – for 53 years of criminalization.

Today, Schirdewahn is active in a group for gay seniors. Many of them have experienced attempts at conversion. Hardly anyone wants to talk about it.

“Hiding is so internalized that you can’t get rid of it,” says Schirdewahn.

In recent months, the fear of public ostracism has increased again in his circle. This is due, for example, to the redistribution of public funds at the federal and state levels, which primarily cuts funding for democracy promotion and political education. “Many of us older people are afraid that repression will start again,” says Schirdewahn. Queer initiatives and support services are particularly affected, such as AIDS-Hilfe, Berliner Schwulenberatung, and the youth network Lambda.

“This is how it starts,” he thought when Bundestag President Julia Klöckner (CDU) decided not to fly the rainbow flag at the Reichstag during Pride Month. He was “horrified” when Federal Interior Minister Alexander Dobrindt (CSU) announced that trans and non-binary persons would be marked with additional information in the population register if they changed their civil status to match their gender in accordance with the Self-Determination Act. Schirdewahn says that many people in his circle were reminded of the “pink lists.”

Schirdewahn only learned that there was a name for what happened to him in therapy in 2020, when the law protecting against conversion therapy came into force. Naming the violence helps, he says. What also helps is talking about it and reading about others, preferably biographies. Next, he wants to write down his life story. But it won’t just be a tale of suffering. Swimming pools will also play a role in it.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights

Queer in One of Most Catholic Countries in Europe: Stimulus or Hindrance?