Queer in One of Most Catholic Countries in Europe: Stimulus or Hindrance?

The text was originally published on Nash Vybir in Ukrainian and in Polish

Contents

In Poland, queer identity within the context of Catholicism reflects a complex interplay of personal and religious beliefs. This is particularly significant because Catholic faith plays a central role in Polish national identity, manifesting in numerous political and social processes throughout the country. While stereotypes suggest that Catholicism complicates the presence and activities of queer movements in Poland, presenting major challenges for queer individuals, is this truly the case? What is the actual relationship between Catholicism and queer people in Poland?

Historical context

As a predominantly Catholic nation, Poland’s connection between national identity and Catholic faith runs deep, though, as researcher Justyna Krasowska notes, this link isn’t always conscious. Throughout certain historical periods, Catholicism in Poland represented not only the embodiment of national identity but emerged as a symbol of freedom. The Catholic Church helped preserve Polish language, traditions, and sense of statehood during the country’s partitions in the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries. During World War II, priests and monks assisted Jews, established underground education systems, and supported the Polish partisan movement. Under communism, Catholicism became a form of quiet resistance against Soviet rule, with religious symbols and gatherings serving as platforms for expressing Polish national identity. When Polish-born Karol Wojtyla became the first non-Italian Pope in a century (John Paul II), his election catalyzed the overthrow of communism. His visit to Poland in 1979 ignited the country’s democratic and religious revival, inspiring the Solidarity movement.

The Catholic Church provided material resources, moral support, and protection to opposition leaders, playing a crucial role in Poland’s transition to democracy in 1989.

John Paul II during his visit to Poland in 1979. Source: Family Home of John Paul II

Church-state relations and queer movement

The church strives to maintain moral influence over Polish society, particularly within the framework of Polish national identity. However, this comes at the cost of tolerance toward queer individuals, often portraying them as a threat to Catholic values. This perspective manifests in public services and statements by high-ranking clergy who characterize queer activism as a danger to family institutions and Christian morality. Church leaders such as Archbishop Marek Jędraszewski, Metropolitan of Krakow, have been vocal opponents of queer rights, comparing queer activism to communism, labeling it a “rainbow plague” and framing it as a threat to national identity. Jędraszewski frequently references “gender ideology” and advocates for protecting traditional family structures.

Marek Jędraszewski leads the procession in Krakow. 2020. Photo: Silar / wikimedia

The Catholic Church in Poland has traditionally aligned with conservative political forces, particularly Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwosc, PiS). This alliance has resulted in various discriminatory policies, such as “LGBT-free zones” and constitutional amendments defining marriage as a “union of a man and a woman.” The implementation of “LGBT-free zones” by several local governments at the provincial level, banning “LGBT ideology” in public spaces, was eventually reversed after EU sanctions and threats to withdraw subsidies from these regions.

Arrests of queer activists during demonstrations remain common, while raids against them constitute regular activities of conservative groups like Ordo Iuris, closely linked to the PiS party. Polish activists and supporters of queer rights, especially those combining queer and Catholic symbols, have faced legal consequences for their actions. Notable was the case of three Polish women charged with “insulting the feelings of believers” for distributing posters depicting the Virgin Mary with a rainbow halo. The charges were later dismissed by the court.

Adaptation of the Black Madonna icon from Czestochowa. Source: wikipedia

The situation has marginally improved with the new government, though not dramatically. Recently, a civil partnerships bill was introduced in the Polish parliament.

Catholic Church leaders offered varying responses – while the Archbishop of Warsaw avoided criticism and stated the church would not interfere with civil partnership legalization, the Archbishop of Krakow expressed firm opposition. Commenting on the bill, Marek Jędraszewski declared that “tolerating evil means the same thing as legitimizing it.”

Social dimension of Polish queer history

Queer history is not very present in the collective consciousness of ordinary Poles. One of its darkest chapters is Operation Hyacinth, conducted by the Polish communist government from 1985 to 1987. While officially justified as a measure to combat HIV/AIDS, the operation’s true purpose was the systematic collection of information about homosexual individuals for repression, intimidation, and control. The police created “pink files” containing personal data of homosexual men, often obtained through coercive interrogations, threats, and moral pressure aimed at forcing cooperation with authorities. This information frequently served as leverage to blackmail individuals in public office.

However, public perception of the queer community in Poland shows signs of improvement. Recent survey by CBOS (Center for Public Opinion Research) indicates growing support for queer rights over the past three years. Compared to 2021, the proportion of respondents supporting the right to openly declare sexual orientation has increased by 9% (reaching 43% in 2024), while support for same-sex marriage has grown by 10% (to 44%). Though these issues remain contentious, acceptance continues to rise. Support for adoption by same-sex couples has also increased, with nearly one in four Poles now endorsing this right—the highest figure since polling began. Support is notably stronger among individuals who personally know gay or lesbian people, women, younger generations, urban residents, those with higher education and income, less frequent church attendees, and those holding left-wing views. Another CBOS survey indicates declining religiosity among Poles. While most still identify as believers, their proportion has decreased from 90% to approximately 86%, with regular religious service attendance falling to a historic low of 34%. This decline is most pronounced among youth, educated individuals, and urban populations.

Queer in Polish culture

Queer symbolism has gained increasing visibility in Polish culture, with a growing number of artistic projects emerging. Notable examples include Krzysztof Tomaszik’s collection of biographies featuring prominent Polish queer artists. Personal diaries of various artists, including Zygmunt Mycielski, offer intimate glimpses into their lives, enriching understanding of Polish queer history. Mycielski’s writings reveal how non-heteronormative relationships persisted during periods of political repression. Despite questions about their complete authenticity, these accounts demonstrate how queer identity endured despite social erasure. Mycielski lived openly as gay during Poland’s communist era, when such visibility was particularly dangerous. His relationship with Stanisław Kolodziejczyk is well-documented in his diaries. As a composer, Mycielski’s work merged Polish traditions with modern influences, especially following his studies under renowned artists like Nadia Boulanger and Paul Dukas in Paris. While his compositions didn’t explicitly address queer themes, his identity reinforced his challenges to conservative musical conventions and serves as another example of resistance against social expectations.

Zygmunt Mycielski and Stanisław Kolodziejczyk, Warsaw, 1957. From the funds of Towarzystwo im. Zygmunt Mycielskiego w Wiśniowej. Source: mycielski.polmic.pl

Queer Christians and the influence of Catholicism

Many Polish parishioners and priests view queer identity through the lens of Catholic doctrine, which considers same-sex relationships sinful. However, this doctrine, like Christianity broadly, also emphasizes compassion and mercy. Even with various interpretations of Catholic teachings on this topic, these perspectives often reinforce conservative attitudes toward queer individuals rather than encouraging acceptance.

In the Polish city of Plock, a participant of a counter-protest tries to stop the Pride march, 2019. Photo: Maciej Luczniewski / Forum

Dorota Hall’s research examines how Polish queer Christians navigate their sexual identity within Roman Catholic doctrine. Her study reveals that many face a challenging choice between adhering to strict religious tradition or seeking more inclusive spiritual communities. This decision often coincides with life transitions such as career changes or relocation. Hall particularly focuses on how queer Christians who maintain their Catholic connections participate in sacred rites like confession and communion. Church doctrine restricts full participation in these rites for individuals engaging in same-sex relationships. Hall notes that queer people in this situation must either follow these rules strictly or develop alternative approaches. The researcher emphasizes how broader social and structural factors influence these choices, noting that individuals from more diverse religious backgrounds typically show greater willingness to challenge conservative Catholic perspectives on queer identity. Hall’s analysis draws on Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological theories about religion’s relationship with other social elements, examining queer Christians’ experiences within the broader context of their lives, including educational background.

Marie Houghton and Fiona Tasker’s research describes how queer Catholics in Poland, particularly lesbian and bisexual individuals, often find ways to maintain both their faith and sexual identity. They might form connections with like-minded believers or develop personal relationships with God outside institutional frameworks. This contrasts with the experiences of gay male Catholics, who often face heightened social prejudice. Study participants emphasize the importance of direct, personal connections with God over institutional religious structures.

Pride in Warsaw, 03 June 2017. The poster reads ‘Christians support the Equality Parade’. Photo: Michal Dyjuk / Forum

Progressive elements within the Polish Catholic community do exist. Some priests and faithful advocate for a more inclusive understanding of faith and sexual orientation, calling for meaningful dialogue about dignity and queer rights within the church.

Nevertheless, tension persists between traditional Catholic teachings and lived experiences of queer Catholics in Poland—while some find harmony, others experience alienation.

International Catholic queer organizations like Dignity play vital roles in advancing change. Its members, embracing both sexual and religious identity, advocate for reforming the Catholic Church’s institutional approach to queer individuals, viewing activism as a means of reconciling spiritual and sexual identity. Dignity provides a global support network for queer Catholics, creating safe spaces for community gathering and experience sharing, while advocating for greater tolerance from the church and society.

Father Tomasz Puchalski, a priest of the Reformed Catholic Church in Poland, openly supports queer rights and advocates for universal respect regardless of sexual orientation. He actively criticizes Jędraszewski’s positions, participates in queer events, and conducts inclusive religious practices, including blessing same-sex unions. Puchalski’s ministry centers on the belief that divine love encompasses everyone, regardless of orientation. He advocates for institutional evolution within the Polish Catholic Church toward greater acceptance of minorities, including queer individuals. Other priests have also worked toward fostering tolerance, though with mixed results. In 2016, a group of Polish Catholic priests supported a queer rights campaign to strengthen church-community dialogue, but their initiative faced swift condemnation from other clergy members who viewed it as contradicting church teachings.

Fr. Tomasz Puchalski. The priest’s avatar on Facebook

Wiara i Tęcza (Faith and Rainbow) represents another significant organization creating safe spaces for Polish queer Christians through various community initiatives.

These examples demonstrate that despite systemic resistance, Poland’s queer community continues to assert itself within the constraints of Catholic doctrine. Moreover, some religious figures actively work toward ideological transformation under challenging conditions. Whether such progress would have occurred without the criticism and intolerance of high-ranking Polish clergy remains debatable. However, while attitudes toward the queer community continue to divide Polish society, queer individuals increasingly find community spaces and opportunities for authentic self-expression. As Poles pay growing attention to their queer history, progress continues, though significant work remains in documenting and understanding the diverse experiences of Polish queer individuals and their relationship with Catholicism.

Read more from the Issue

Nothing Found

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

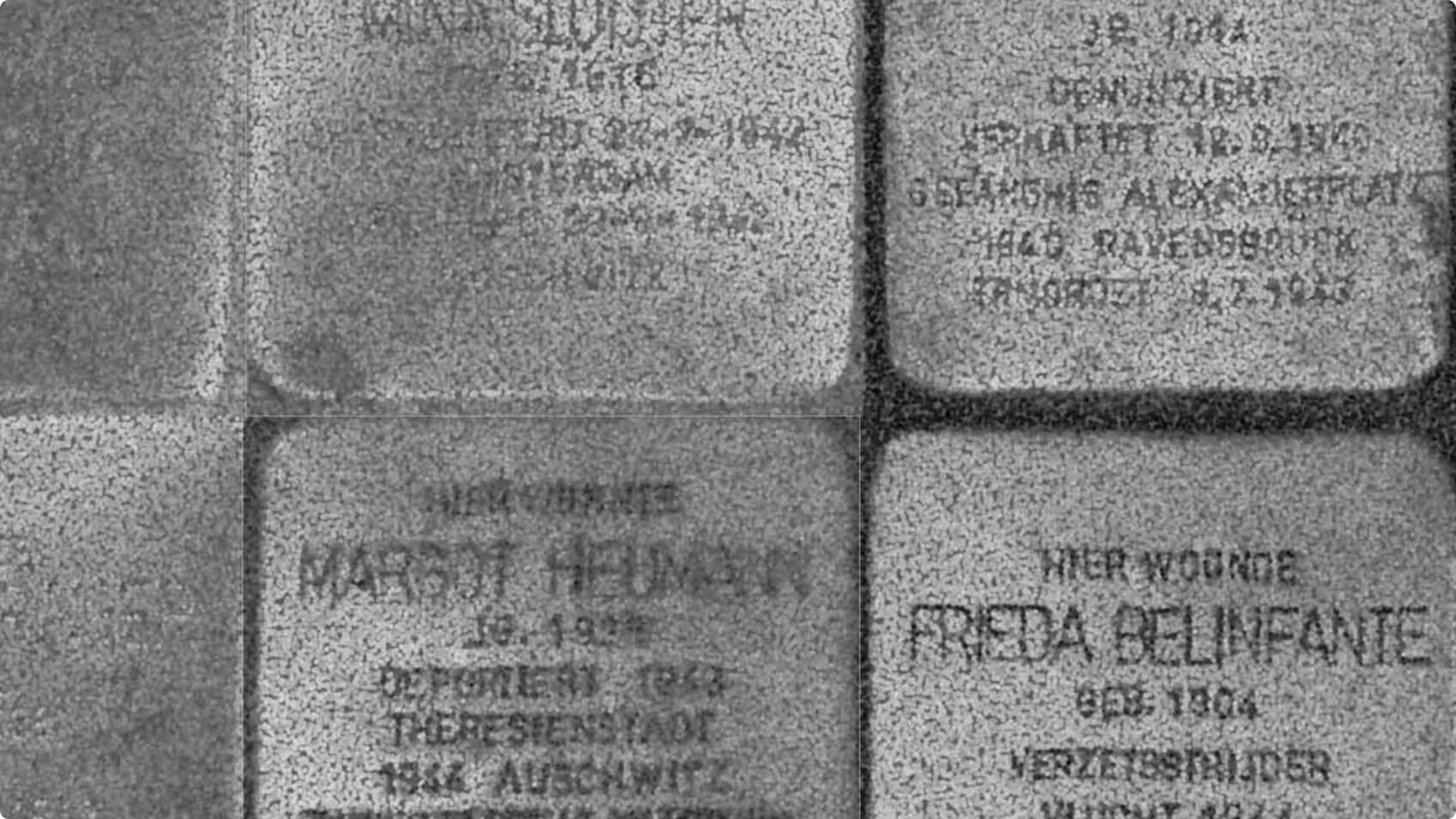

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights