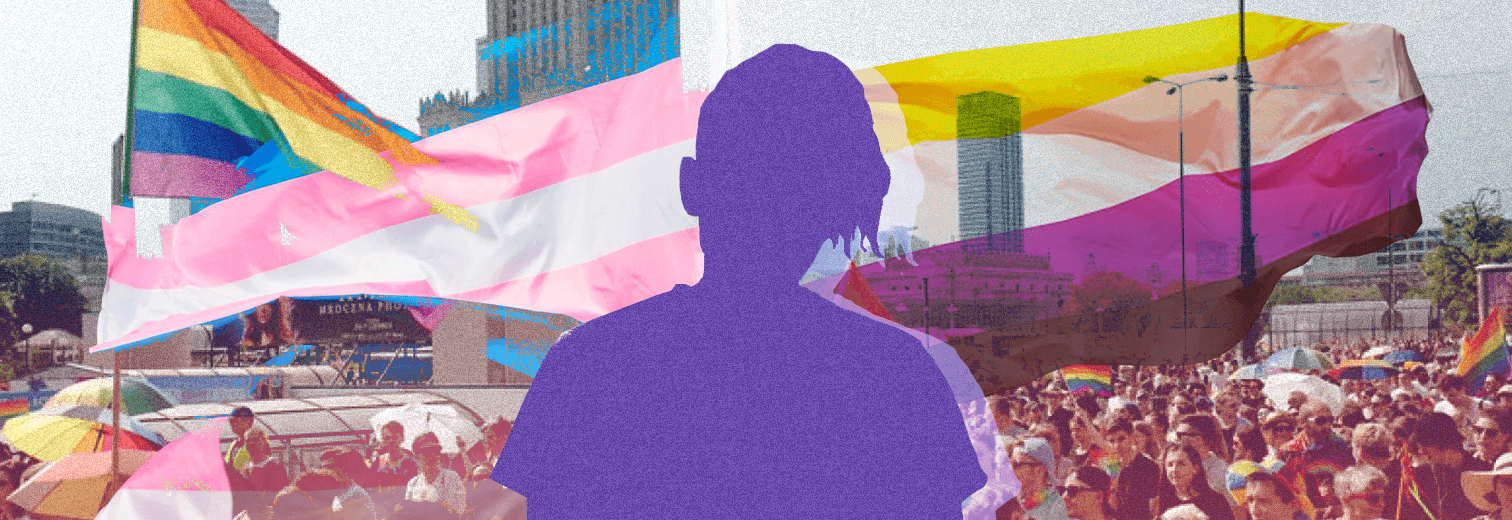

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

The project was originally published in Polish on Oko.press and in German on Siegessäule

photos: Anton Ambroziak

Many of these stories should never have happened. Witold Smentek changed his gender marker in 1937 despite no regulations allowing this in the Second Polish Republic. Before the war, Alex went to theatres in Lublin wearing women’s jackets and high heels. How do their biographies connect with the experiences of trans people today? Read their (impossible) stories

The text was originally published on the occasion of International Transgender Day of Visibility, which is celebrated on 31 March.

How did queer history begin? Many people would say with the first brick thrown during the riots at the Stonewall bar in the United States in 1969. However, this image of emancipation comes from across the ocean. In Europe, we have our own heroes and many untold stories.

Comparing the experiences of Germany and Poland, we look at how transgender people described themselves before the war and today. The biographies we follow are separated by 100 years, a completely different language and socio-political context, but each of them – and all of them together – form an open collage to which we can constantly add new fragments.

Once upon a time: Transgender identities in Germany and Poland

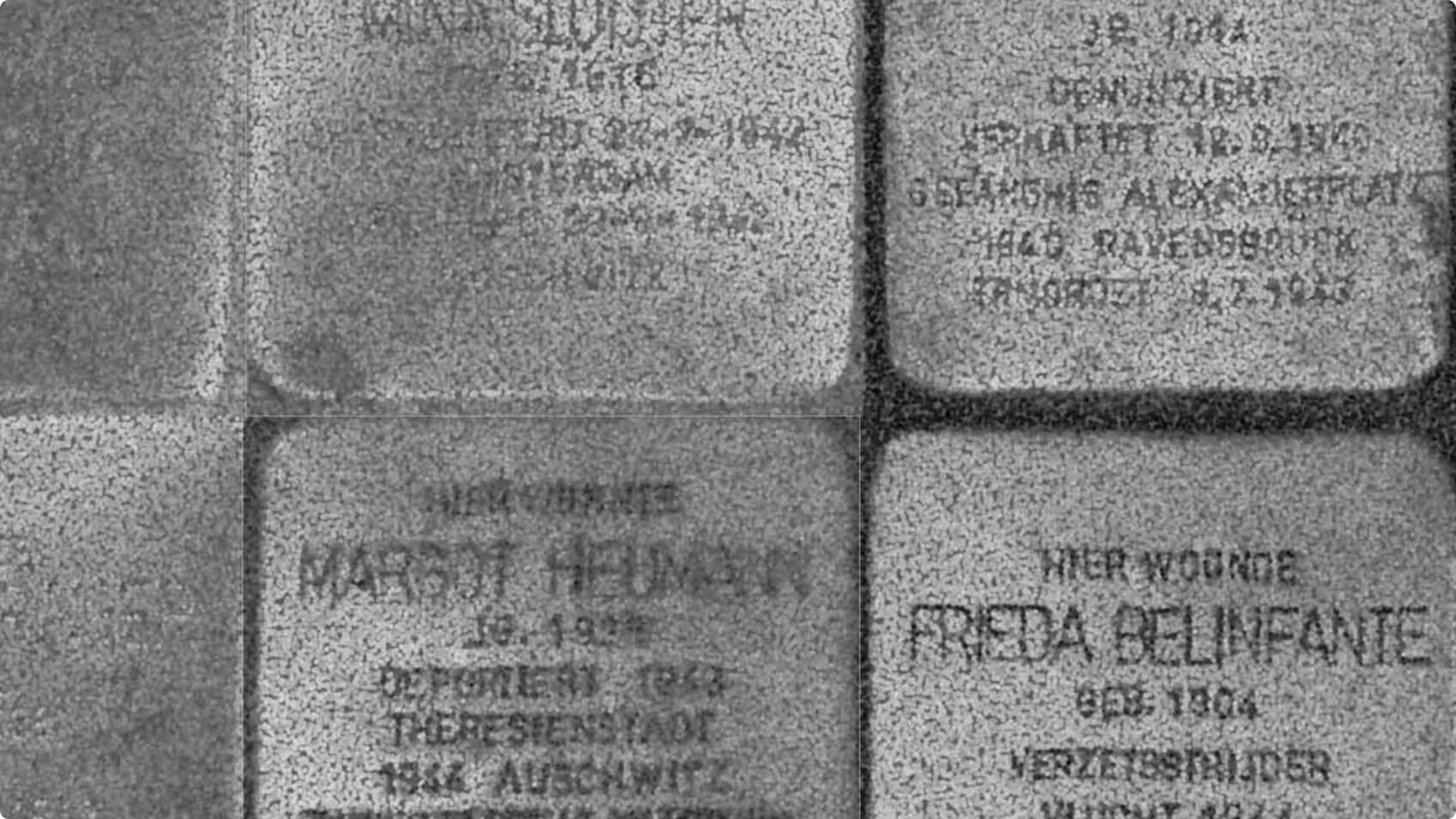

In August 2023, a new memorial stone – a Stolperstein – was placed in front of a residential building on Hagelberger Straße in Kreuzberg, Berlin. ‘Käte Rogalli lived here,’ reads one of over 100,000 markers installed at the last known addresses of Nazi victims.

Eighty years after her death, Käte became the first transgender woman to be honoured with such a stone.

Her real name is engraved on it, not the one she was given at birth.

We cannot be sure how Käte Rogalli would identify herself today. Her story began during the Weimar Republic and ended during the Nazi regime.

Over the last century, the terms we use have evolved and changed. ‘However, queer people can be found in historical sources such as criminal and medical records,’ says historian Kai* Brust.

According to Brust, it is not that we lack terms to describe pre-war identities, but rather that historians in the past showed little interest in the lives of gender-non-conforming people. Käte Rogalli’s story only came to light thanks to Brust’s research.

The golden age of the Weimar Republic

Käte Rogalli, who was assigned male at birth, received a ‘transvestite certificate’ in 1926, which officially allowed her to cross-dress in public – the laws at the time prohibited dressing as a person of the opposite sex – and change her name. This was achieved with the help of Magnus Hirschfeld, a pioneer in the field of sexology, who coined the term ‘transvestite’ and under whose patronage the first sex reassignment surgeries were performed.

In the 1920s, ‘transvestism’ was a broad category that included both cross-dressers and people whose identity did not match the gender assigned to them at birth. Although it was viewed strictly through the lens of medicine, as a biological error, for people like Käte, the term provided some legal protection before 1933.

Increased persecution under Nazi rule

With the advent of the Nazi regime, the situation for queer people changed dramatically. Male homosexuality was considered a crime under Paragraph 175, a provision inherited from the German Empire’s 1871 criminal code. The Nazis also stigmatised other identities, including ‘transvestism’ and alleged ‘lesbianism’ (we use historical terms appropriate to the period). The rigorous ideals of Nazi ideology considered any deviation from assigned gender roles a threat to the ‘Aryan’ race and the family structure it promoted.

The invasion of Poland in 1939 marked the beginning of World War II. For a short period before the start of the German occupation of Poland, there was no legal basis for prohibiting sexual acts between men: the native provisions of the criminal code criminalising homosexuality had been repealed in 1932.

This made it easier to place many fluid identities in the realm of homoerotic desires.

Homosexuality was recognised, while transgender identity was foreign and incomprehensible. Queer sex work, however, was still controlled under Article 207 (so-called homosexual prostitution). Joanna Ostrowska, a historian and researcher of queer biographies, points out that: ‘The history of queer Poland in the 1920s and 1930s is mainly a history of pleasure, rather than of community building in the legal sense. This is unique on a global scale.’

In the German Reich, people who transgressed gender norms were often considered by the state to be ‘anti-social’ or dangerous. Their persecution often depended on the reaction of neighbours, acquaintances and local authorities.

Käte Rogalli’s ‘transvestite certificate’ was revoked in 1936, and the Gestapo forced her to dress as a man. When she returned to women’s clothing, she was reported – probably by her wife or mother, who did not accept her ‘lifestyle.’ In 1937, she was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where she was forced to perform hard labour, and then she was locked up in a psychiatric hospital and labelled ‘psychopathic’ because of her gender identity. Käte Rogalli died in 1943.

In search of cracks in biographies

Understanding the scale of persecution against transgender people is extremely difficult because their identity, as described in criminal or medical records, was determined by their perpetrators.

Today, researchers are tasked with looking for cracks in biographies.

Ostrowska refers to these as ‘queer moments’ – points at which identities collapse or branch out, diverging from or crossing existing norms. ‘My favourite example is Krystyna Modrzewska. Her biography shows that a person can change their perception of themselves many times throughout their life. And identity does not have to follow the rules of medicine or the law,’ says Ostrowska.

Krystyna Modrzewska (Mandelbaum) was born in 1919 into an assimilated Jewish family. Modrzewska is mainly known for her activities in the Home Army, the Polish resistance movement during World War II. Early fragments of her biography contain many references to individualism and rebellion. Her first identity transformation, which involved changing her surname from Jewish to Polish, was intended to give her a better chance of survival during the occupation.

Modrzewska studied anthropology in Bologna, where she met people who questioned their own identities and bodies. This influenced her adoption of the then affirmative concept of ‘transvestite’, which she found in the writings of Magnus Hirschfeld. She later published books under the pseudonym Adam Struś, and at the end of her life, to honour her Jewish mother, she changed her name back to Krystyna Frenkiel.

What makes Modrzewska’s journey unique is the fact that her process of trying on different identities was not confined to private correspondence, but was expressed publicly.

In the 1960s, in the book Jestem kim innym (I Am Someone Else), Adam/Krystyna described the experience of growing up feeling alien in a female body.

‘Later in life, when I was trying to understand my taste in clothes, I even wondered if this complete lack of interest in clothing and my love for “simple, English” forms had any influence on my transvestism. Of course not. The relationship was quite the opposite,’ they wrote.

It is not for us to decide whether today’s term transgender would be an appropriate umbrella for Modrzewska/Strusia. However, this story shows a personal search for the inexpressible.

‘In my latest book, Ślady [Traces] (to be released in September 2025), I try to create a mosaic of quotations. I want the characters to speak for themselves and the readers to see a multitude of possible scenarios. Where this is not possible, I point to small cracks in their identities. I have one character, Alex, who was persecuted four times in pre-war and post-war Poland for various sexual offences, who talks about himself using only male pronouns,’ says Ostrowska. ‘But many of the statements from reports and newspapers mention a woman’s dressing gown and jackets, high-heeled shoes, a soft, feminine voice, mannerisms, a smile, or a lack of shame in taking out a powder compact in the theatre.’

After each episode of persecution, Alex tried to create a substitute for a new identity. His story has no ending, and Alex’s fluidity is difficult to translate into today’s understanding of identity.

The first known case of gender reassignment in Poland

The story of Witold Smentka is a spectacular breakthrough in legal matters. Born in 1910 in Kalisz as Zofia Smętka, he was the first person in Polish history to change his gender designation in official documents. Until 1937, he was an athlete, winning the Polish championship in javelin, and was successful in cross-country running, table tennis and hazena (Czech handball). His masculine appearance exposed him to rumours of ‘hermaphroditism’ – as intersex or gender-diverse people were referred to at the time.

Smentek, taking advantage of both good and bad press, made his transition a public affair.

‘I had felt for a long time that I was being watched, I saw smirks and heard unpleasant rumours. So I made up my mind and said: I can’t be a woman anymore. I’m going to become a man. I’m having the operation next week,’ Smentek wrote in his statement to the media.

In April and May 1937, Dr Henryk Beck performed two sex reassignment surgeries on Smentek at the Dzieciątka Jezus University Hospital in Warsaw. The details of the operations remain unclear due to the destruction of medical records, but Smentek’s story made the front pages of newspapers. The Łódź Echo wrote: ‘Zofia Smętkówna ceased to exist. The new man burst into tears…’ In a short statement to journalists, Smentek said: ‘I am happy that the operation is behind me and that I can finally start a new life.’

When the case for changing the gender designation in the documents reached the District Court in Kalisz, the court had no doubt that it was a man standing before them.

And on behalf of the Second Polish Republic, without any law to refer to, it issued a ruling confirming Witold’s identity: ‘This story should never have happened because no path was laid out for it,’ comments Ostrowska.

Compared to Germany or even Czechoslovakia, there were no queer organisations or press in Poland fighting for LGBT+ equality. ‘We can only speculate whether the public handling of the case, the stories of undeserved suffering and “intersexuality” were Witold’s real experience or a conscious attempt to live his life in the conditions that were possible at the time,’ says Ostrowska.

‘And that’s why I always say that the category of queer is obviously ahistorical in relation to the pre-war period, but at the same time it is the most fair to the people I describe. It takes away the responsibility of deciding whether someone was gay, lesbian, trans or inter. It points to the whole spectrum of possibilities and leaves history open. Because writing a biography is like creating a collage to which we can always add something new,’ adds the historian.

Today: 9 biographies from Warsaw and Berlin

Filipka, 34, art historian, performer, Warsaw

I was born in Katowice in Upper Silesia. I lived in a classic mining estate near a mine, where people lived in tenements and spoke Silesian. My family was one of the few that had been transplanted there; my parents came from Masuria – we no longer identified with anything, neither with the lakes nor the mines.

Probably unconsciously, my parents started a tradition that if you don’t have a history, you have to reinvent yourself.

I started looking for myself through art. It was another queer breakthrough – I was doing it in a working-class environment where most people didn’t have higher education. It started intuitively. There is an old Polish tradition where, on a child’s first birthday, a glass, a banknote, a book, a piece of string and other objects are placed in front of them. Whatever the child grabs first is what they will become in the future. I grabbed a notebook and a pen and started drawing.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

When my queer desire began to awaken, I had nothing to relate it to, I didn’t know any books, films or people like that. However, I drew women obsessively. At the time, I thought I was inventing my future wife. I played all sorts of games, for example, I drew the same woman 70 times, each time at a different age. When I finished one cycle, I started a new one. As a teenager, when I started going on dates with boys, I drew our trysts.

Apart from my notebook, all my desires were a secret.

I knew that being gay was something terrible. With my first pocket money, I bought a patterned T-shirt with flowers on it. When my parents saw it, they told me to give it back, throw it away, there was no way I could wear it. They said I looked like a ‘faggot’, that people would laugh at me, point fingers and beat me up. But to me, that colourful T-shirt was associated with being an artist.

With the first big money I earned in Brussels, I bought myself colourful scarves and flat caps, because I thought that’s how people involved in art dressed in the West. I didn’t know I looked like a gay man from a museum catalogue. And when I finally met a gay man, which was only when I was 20, I was afraid of him at first. But then, being friends with him was like a window to the world, it also reminded me of European life.

But I didn’t really come out until I was 22, when I went to study in Berlin. There, I discovered dating apps with men from all over the world – it was like a golden age. I explored the whole city – I visited all the neighbourhoods, social classes, ethnic and national minorities. When I returned to Katowice, I was so full of experiences that I told my parents I was gay.

They said they would kick me out of the house, so I had to backtrack in order to finish my studies.

I ended up in Warsaw somewhat by accident, where I started working in an art gallery. And that was another shock. Firstly, I became independent from my parents, and secondly, I distanced myself from my past. I left behind everyone who knew me as a straight boy. And queer began to emerge as something completely different – not an insult, but something serious, a kind of language, an artistic practice. I started going to parades and demonstrations and getting to know a world that was so different.

But Filipka appeared just like drawing – intuitively, in a frivolous game. I was bored with how I looked, I felt that I had outgrown that version of myself. Before a party, I texted a friend to ask if she had any dresses. She was the one who dressed me up as a woman for the first time. I wore a gold, transparent dress, a model worn by Kate Moss. Not once did I ask myself what would happen if someone saw me in a less ‘trans’ version. It was completely natural.

At first, I only showed up like that on the dance floor, but it quickly got out of hand. I couldn’t keep that part of me confined to the world of fun. People at work found out about my other side from photos from parties. Suddenly, the question arose in my circle: how far would this go? Would I start coming to work like this?

Artists may occasionally express themselves differently, but in an office job, you have to go to the post office, to government offices, work with technicians. A man in a dress? It’s not appropriate. Some people also wanted to say, ‘Wow, they support me so much,’ but I didn’t know what they meant.

For me, there was no difference between being Filip in a dress or Filipka in trousers.

Then someone introduced me to the work of Paul Preciado. His books were kind of shoved into my hands so that my identity wasn’t just wild partying, so that I had a language for it. That’s when I realised that there were words for my frivolity, and that a trans person could be a star of critical theory, not just sit in the basement of a bar. Then came various offers – to participate in performances and films.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

Three years ago, I quit my full-time job at a gallery to start my adventure as a freelance artist. I suppressed my childhood dream for a long time because I was sure that a miner’s daughter involved in art would be a financial disaster. But today I think it’s the most sensible thing I can do. It’s the same with gender, I choose sensibly, but I don’t want to be bored, life is too short for that.

I understand that some people need a fixed identity to feel secure. But for me, different identities work well in different situations. When I go to Biedronka, I don’t wear high heels and a dress. It’s practical, down-to-earth, how I organise my life. Femininity allows me to create more turbulent relationships. But when I need to focus on work, I’m that boy again. Dressed like this, I really can’t do anything concrete, it distracts me too much.

I just operate in these two extremes, I play with it and feel grounded in it. When you warm up for a performance, the first thing you learn is what it means to ‘stay grounded’. This is a key skill for me, especially in times of political turmoil. Regardless of whether marriage equality is passed in Poland or Trump says there are only two genders, it doesn’t change who I am or what I do.

Sebulec, 35, visual artist, Warsaw

To this day, I still think I would like to be born a boy again. There was a time when I prayed to God for this. I felt like I had drawn the wrong card.

Then my mum told me that women have it worse in this world. For a long time, I thought that I was just like everyone else, because if women had a choice, they would prefer to be men.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

As a child, I gave clear signals that I liked boy things. I stole my cousins’ Action Man toys and clothes. I have photos from celebrations where I am dressed in dresses and standing awkwardly with a sour expression on my face. Later, I realised that I liked girls and that there was more freedom for ‘unfeminine’ behaviour in the lesbian world. There were also a lot of toxic patterns carried over from heteronormativity, but I remember it as a time of first romances, of exploring falling in love.

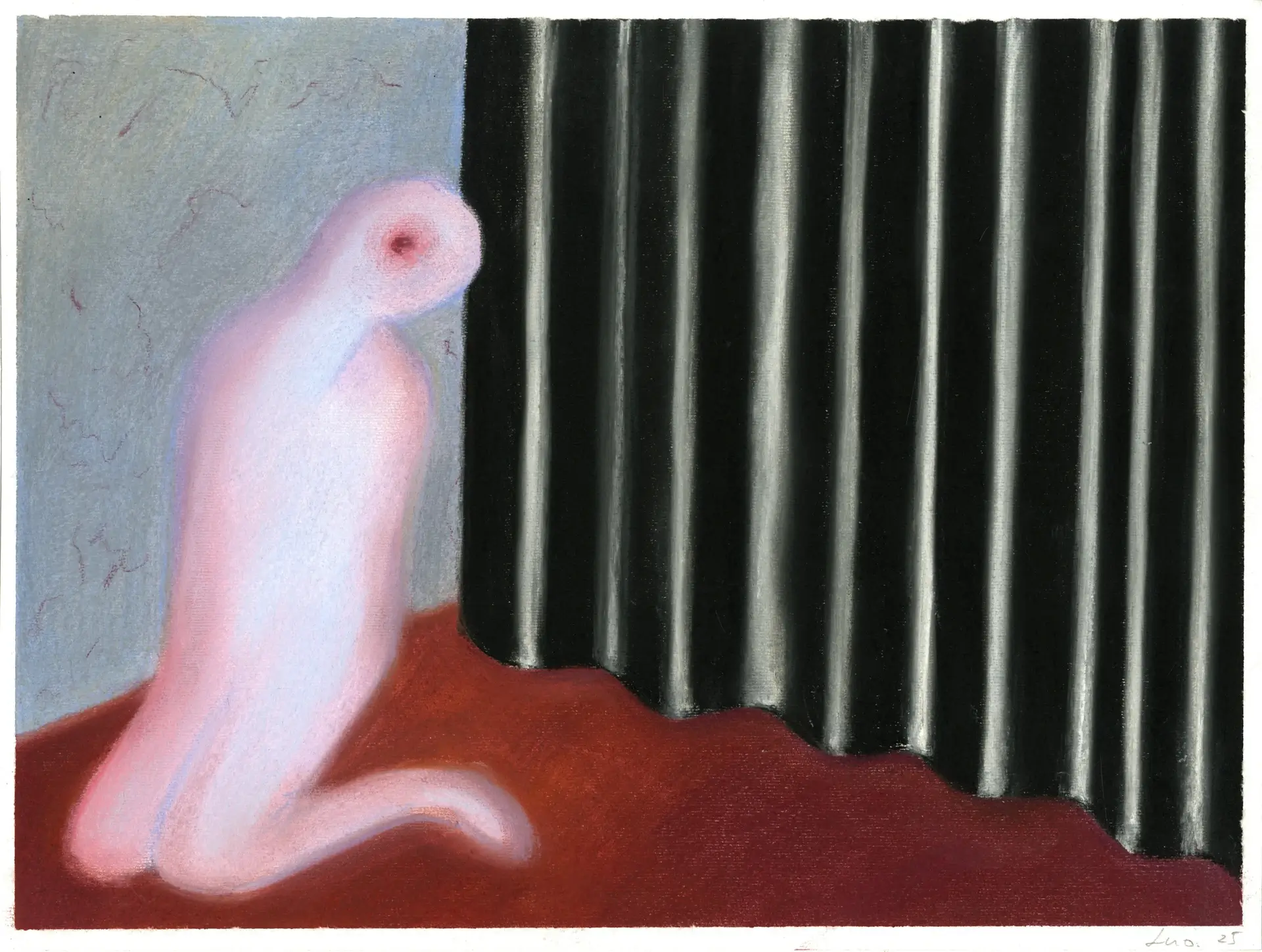

I don’t even know why, but I started downloading photos of queer people from the internet. I created a huge visual database of non-normative expressions. I drew and painted different characters.

Then came my fascination with female bodybuilders.

The contrasts between the body you have and the body you can create on your own or with the help of substances totally appealed to me.

For several years, I lived in the limbo of transition. I told my close friends that I wasn’t a woman, but I couldn’t name it. The breakthrough came from a powerful crisis. I was depressed. I had to start thinking about what could make me feel better about myself. And then Sebulec appeared.

I was going through a phase of wearing tracksuits, reliving my adolescence as an adult man. I started training MMA, which sculpted my body and boosted my confidence. I liked walking around with a bruise under my eye after sparring, I felt like a badass. I never looked for trouble, but I was much less afraid and didn’t shy away from bullies who were taking up space.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

My art has also changed. Previously, I felt a feminist mission to affirm femininity, now I’m taking up the banner of transsexuality. Sculpting the muscles and silhouettes of my characters is a process of creating myself, of satisfying my fantasies. My work is heavily influenced by the world of games and fantasy, referring to both childhood dreams and adult desires. I’ve always had a soft spot for big cartoon animals, such as Bowser from Mario Kart, Bebop and Rocksteady from TMNT, Pumbaa and the Beast from Beauty and the Beast.

The fact that I look and sound the way I do today has given me the strength to go out there and share myself and my art with people. Maybe I would prefer to be a cis boy, but I never hide the fact that I am trans. I know that it is also important for my students to see their identities reflected in someone else.

When there was a queer art exhibition in Bytom, the homophobic capital of Poland, I saw how much people 10 years younger than me wanted to talk about it. Having a community where we can be ‘weirdos’ together, but in a positive sense, is great.

Dana, 23, dancer and choreographer, Warsaw

I started dancing when I was 11. I saw the film Step Up and quickly signed up for classes. I tried everything: breakdancing, hip-hop, modern dance. One of the teachers started teaching voguing, although she was just beginning her adventure with us. I was afraid to go because, you know, it’s either girls or ‘fags’ who dance.

In Kremenchuk, a city of 200,000 in the geographical centre of Ukraine, lesbians and gays were ridiculed, not to mention trans people.

When I started dating boys, going on dates was terrifying. It was like the plot of a thriller. My first kiss? In total secrecy: by the river, on a wooden log in the middle of nowhere. I was shaking all over as I drove there. But desire and excitement always won out over fear. That’s how I entered the world of ballroom.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

There was no talk of transgenderism. Sometimes I heard jokes that ‘a boy dressed up as a girl’. Before going to sleep, I fantasised that it would be cool to be a girl, but I thought it was impossible.

When my feet grew to the size of my mum’s, I started stealing her high heels.

I liked the summer sandals with wide platforms the most. This year, I want to buy the same ones; it will be my manifesto.

I also painted my face in secret. At summer camps, we had a game where for one day the girls had to ‘pretend’ to be boys and the boys had to pretend to be girls. For me, it wasn’t fun, it was a celebration, my happiest childhood memories.

All these experiences were suspended in the realm of the impossible. It was only when I was an adult, after several years of functioning in the queer community, that I began to reveal my femininity more and more.

Before one of my trips abroad, I was verbally attacked in Warsaw because I had painted my nails. When I came back, I completely fell apart. I didn’t want to pretend to be a boy anymore – I even went through a phase where I went to the gym and gained weight to make guys like me more. There was no way I was going back to what I had been. But the prospect of transitioning terrified me.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

The months before my transition were very difficult. I hated myself and my body, and I fell into depression. When I first went out in a skirt, I was sure everyone knew. I felt exposed and judged. And sometimes it was true, because I encountered aggression more than once, but sometimes the fight was only in my head. Today I can say that I am proud of my story, but it took me a long time to truly believe it.

Rob, 35, actor, Warsaw

There is one photo I tried to find on my 30th birthday. I am six, maybe seven years old. I am in my parents’ old living room, wearing a red T-shirt with a pink strappy dress over it, finished with white lace. I’m sitting with my legs crossed, looking flirtatious, holding a plastic gun in my hand. I’m making a face as if I’ve just blown smoke after firing a shot.

The last time I saw that photo was when I was about 15. At some point, I hid it away because the femininity I saw in myself paralysed me. This story sums up what happened to me over the years: from the true freedom I felt only in my early childhood, through periods of shame and liberation.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

It was only in the last five years that I gave myself the right to express something I later called non-binary. It was a relief, because for most of my life I felt out of place with who I am. For a moment, I was able to let go of expectations about my body and identity.

I also remember moments that used to embarrass me, but today they amuse and touch me. When I was a child, if someone asked me if I was a boy or a girl, I would answer that I was a girl. When they asked in reverse, if I was a girl or a boy, I would answer that I was a boy.

There is also the story of my birth, when my mother had to hold me out of a second-floor hospital window so that my father could see my penis, because he didn’t want to believe that I was a boy. Firstly, only girls had been born in my family, and according to my aunts and grandmothers (folk beliefs), the shape of my belly indicated that I would not be a boy. It was pointed for a boy and wide and hip-shaped for a girl (sic!).

I remember my own surprise that I wasn’t a girl.

When it came to social roles, I tried to fit in, but I was always more of a paramedic than a police officer. My family took care of me, I was a weirdo, but also their beloved ‘Bolo’. I have a memory of walking with my grandmother and her friends to the forest to pick mushrooms — I was carrying a bag, had a parting with coloured streaks in the middle of my head and my face covered with diamond stickers. Everyone said I was an artistic soul and that I would grow out of it.

At school, the leniency ended, and humour was my shield for years.

It was a great starting position when everyone calls you a ‘sissy faggot.’ Teenage years are a painful time in general. In a homophobic and transphobic world, you can either hate yourself or create an alter ego. And a good clown never gets cut down. It was my way of surviving, of belonging. Of course, there were wounds underneath.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

Once, a friend of mine told me when he was drunk that he would do anything not to be gay. It hit me hard, because even though I have a lot of wounds, I want someone to write on my gravestone that my life began with being queer. Really, all the adventures, pleasures, relationships, all the complexity.

Does that mean I feel free today? No, but I’ve learned to function with these different layers. I can’t get rid of the clown, but I can activate and deactivate him depending on the situation. He’s an inseparable part of me. It’s the same with scars. I used to think that as soon as I got rid of them, I would automatically be happy. Today, I try to come to terms with them.

Non-binary identity can also be uncomfortable for me, because the declaration itself does not erase the fact that I function in a specific social context and have a specific body. I won’t hide the fact that non-binary identity emerged as a response to my reluctance to define my identity.

Something that has been oppressive for years cannot bring me relief or satisfaction.

I am 35 years old, who cares who I am in my adult life? For me, the power of non-binary lies in the fact that you are not a woman and you are not a man. You are somewhere in between, or you are neither. Or you are both.

I’m tired of defining what it means to be non-binary, because the whole power of the term comes from the fact that you don’t have to fit into any box. You’re elusive, you’re yourself – and that, of course, changes so many times in the course of your life.

Alin, 25, actor, Warsaw

Many people reduce transsexuality to a question of the body, which is both private and public. I think there was only one period when I felt that it belonged only to me. It was during the COVID-19 pandemic, when I was spending all my time at home, feeling comfortable with how I looked and sounded. But the idyll ended when I saw anyone else. That’s when my body took on new meanings: my voice was too high, my feminine curves too exposed.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

When I gained huge visibility playing in the Netflix production Fanfik, the dysphoria that had been hidden came to the surface. There were a lot of conflicting feelings: for the first time on such a scale, people could understand my trans identity. At the same time, I also felt a great responsibility not to make a mistake about my identity, because the entire LGBT+ community was watching me.

These demons were mainly in my head.

As a 10-year-old kid, I was sure I was a boy. At home, I couldn’t express myself, sometimes I argued, sometimes I lost and had to improvise – I hid my clothes in my backpack and changed at school.

I sought freedom by running away from my parents, but online I was always who I wanted to be. Then I created various other personas, for example in high school, when I ran for student council, I went back to feminine endings and a feminine name. After my first film role, overwhelmed by the part of a middle-class girl who is just window dressing, I shaved my head in a fit of rage.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

There has been a lot of struggle in my life, but only recently, when I started HRT [hormone replacement therapy], have I felt that you can play with your identity and gender. I don’t have many examples of queer excitement yet, but I think the most enjoyable thing is knowing that as a non-binary and trans person, you can just have a normal life. And there are more people who live just like you, sometimes completely unnoticed.

They study, go for walks, cook, party – they’re not just on the internet or Netflix, but right under your nose.

I can’t wait to experience how the long-awaited changes taking place in my body will affect how I function in society. It’s an exciting vision – to live in harmony with yourself instead of being dictated by other people’s expectations.

Oliwer, 32, goldsmith, Warsaw

Recently, after many years, I was looking through a blog I wrote at the beginning of my transition. I was 17-18 at the time. At times, it was like reading someone else’s story. The most foreign-sounding passages were those in which I was 100% sure of who I was, what I thought and what I wanted. I guess that’s typical for young people. Today, I more often think that I ‘don’t know,’ which is sometimes frightening and sometimes liberating.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

When I was a child, I thought it would make more sense if I had been born a boy, but I was sure there was nothing I could do about it. I wasn’t the rebellious type, and to this day I perhaps too often trust that rules are there for a reason and make sense. I have a lot of opposition to injustice, inequality and lack of empathy, but when it comes to taking care of my own needs, I still find it difficult to feel and express opposition.

I remember when I first came across the word ‘transgender’, I wrote it down. I found an explanation online that a trans person is someone who feels that they are not in their own body. It moved me and I thought it must be terribly difficult, but I didn’t feel at all that it could also be about my own relationship with my body – probably because my dysphoria affected several areas, not my entire body, which from an early age had a rather typical boyish and athletic appearance.

Mostly, I felt that my voice before transition didn’t resonate with how I felt inside. During puberty, I experimented with different forms of expression – in primary school, this involved name-calling at one point and even an experience of exclusion that I only understood years later.

Then I had a moment of emancipation and discovered the queer-female community, where I found a sense of belonging. The feeling of queerness that was awakening in me at that time is still one of the key elements of my identity today.

I returned to the topic of transness when I was about 16. There were already quite a few English-language channels on YouTube where trans guys shared their experiences. I think at first I was naturally fascinated by how much you can influence your appearance and body – because it’s actually amazing how powerful hormones are and how changeable and flexible the human body is. I quickly began to explore the subject from a psychological and social perspective, and in this broader view of transsexuality, I saw much more of myself than in that first definition.

photo: Anton Ambroziak

One of my favourite moments from that time was when I heard my chosen name for the first time in class during roll call – I froze for a second, then said ‘I’m here!’ enthusiastically and louder than ever before, and exchanged joyful glances with two friends. It’s quite symbolic of how, when I started to be seen as I felt, there was room for joy, boldness and pride.

Around the same time, I started a blog documenting the changes I was going through. It was a way of showing my gratitude, of giving back what I had received from trans guys online, but as a result, I received a lot of support and attention myself. I experienced something strange: on a daily basis, I was separated from the trans community and completely anonymous in my city, even though I had thousands of followers and online friends in several parts of the world. For a while, I tried living stealth [without revealing my gender identity – ed.], but I quickly realised that it wasn’t for me, that I couldn’t see any chance of being free, authentic and having truly close relationships with people if they didn’t know this part of me.

Because of the times I grew up in, the connotations of the term ‘transsexual’ [editor’s note: a term that does not diminish the complexity of the concept of gender, referring only to biological, but not psychological or social, conditions] may be different for me than for younger trans people today. For me, it simply refers to my medical transition, although this is only part of my experience.

Sometimes, when I talk to someone completely outside the community, I decide to simplify and use the term ‘transsexual’ instead of ‘transgender.’ In such cases, I assume that people in Poland will understand what I mean without delving into the diversity of experiences behind the better terms available today.

Today, I am more concerned with queer identification. Since beginning my transition, I have met and formed relationships with men – I am also curious and open to relationships with women, although it turns out that in the latter case, gender stereotypes and the urge to jump into roles that I am completely uncomfortable with come back to me.

Even though I find myself saying ‘I don’t know’ much more often than I used to, I strongly believe that my sense of queerness will remain with me, even if, for example, I become a parent one day and am in a long-term relationship that looks conventional and heteronormative from the outside.

Eliot, 39, tour guide, Berlin

It’s hard for me to access my memories from before I came out. It’s fascinating how deep I have to dig. I think many trans people would describe it as a beautiful moment if they could go back in time and say to their younger selves, ‘Don’t worry, one day you’ll be a man!’ If I could travel back in time and talk to myself at the age of nine, to be honest, I think I would be terrified.

I grew up in a small town in Yorkshire where I didn’t see any transgender people, only negative portrayals of them in the tabloids.

My therapist later told me that it was no wonder I didn’t know about it until I was 34, as I never had the space or freedom to figure it out.

photo: Marit Blossey

I always felt uncomfortable around women. I never wore make-up or dressed like my friends. When I was a teenager, I became a goth and covered my whole face in paint every day. I was denying myself, even to myself. I wish trans people had been more visible back then.

For a while, I thought I was a lesbian, but that didn’t feel right either. After college, I moved to Japan for five years, where discovering my gender identity wasn’t really possible either. Eventually, I moved to Germany because I was in a D/s relationship [ed. – a relationship dynamic in which one person is dominant and the other submissive] relationship. Looking back, it was my coping mechanism – I didn’t know who I was, so it was easier to let someone else decide. It wasn’t violent, it just wasn’t what I needed.

And then the pandemic hit. I had nothing to do, so I had time to think. I tried dressing like a man, just for fun, because everyone was making these drag videos while sitting at home. It felt more natural than dressing like a woman. Everything just fell into place. That was five years ago.

I was born in 1985 and grew up in the nineties, when calling someone ‘trans’ was considered a joke. Now I use the term to refer to myself – it seems provocative, but I try to be careful with it. The negative portrayal of trans women and the invisibility of trans men meant that I never had a chance to understand any of this when I was young. If it had been different, I might have experienced too much hatred from those around me, and I might even have killed myself.

I regret going through puberty as a woman. I would have been gay in northern England in the 1990s, which wouldn’t have been easy, but maybe I wouldn’t have had all these mental health issues related to gender dysphoria – depression, eating disorders. It’s sad that I couldn’t come out earlier – it would have been easier for everyone, especially my parents.

When I transitioned, almost everyone eventually accepted it because I was visibly much happier. I stopped drinking alcohol. I am a perfect example of what can happen when a trans person receives the right support at the right time. My transition from coming out to top surgery (mastectomy) took only a year and a half. Everything worked out. When trans people get what they need, they can focus on other important things – like life.

At work, I wear a large trans flag earring because being seen as a trans man is important to me. I am a feminine, camp man with a vagina and no beard, but I am definitely a man. When I first came out, I went through a phase of suits and ties, it was like my trans puberty – but I don’t think about that anymore. I wear what I like and I don’t care how I’m perceived. Of course, if I were more butch, I would be perceived as a cis man, but that would be a damn tedious process of pretending. I’ve done that long enough to last me a lifetime.

I’ve always admired gay men who express their femininity. The way they are ridiculed for their femininity, the way that femininity is rejected, reflects the way trans men are treated. At the root of this is misogyny. I like to play with expectations. That’s why I love winter swimming and found a small group of trans winter swimmers. Some people see it as a big challenge, but for me it’s soothing. The contrast between my slim, hairless body and this demanding activity makes me smile.

History often repeats itself, but if we learn from it, the 2020s will not be a repeat of the 1920s. Transgender people are often seen as either a threat or victims, and this narrative is nothing new – it has been present throughout human history. Maybe we could stop repeating it. Some people like to ask the question, ‘What is a woman?’ I heard a beautiful definition that said the only thing all women have in common is that they know they are women. Maybe that’s all we can say about anyone.

Chrissie, 50, tour guide, Berlin

Before I moved to Berlin, I lived in Copenhagen, which was like Berlin 30 years ago, but now it’s a city for the rich. Over time, diversity began to disappear. I thought it would be easier to blend in in Berlin, hide in the crowd and live a normal life. I just wanted to do ordinary, everyday things – get up, send the children to school, work, put them to bed. I don’t want to stand out. Besides, I love German history, and that’s partly why I moved here.

I first came out as transgender at the age of 16, in the Danish countryside in the early 1990s. Those were completely different times. I started taking hormones. However, I had to fight hard to get a prescription because the Danish health department tried to convince me that I wasn’t really transgender. This led me into a deep depression, and I was on the verge of suicide. I decided to detransition, thinking that was the only way I could help myself.

photo: Marit Blossey

For almost thirty years, I convinced myself that it was just a phase, that maybe I was just gay, but I never really fit in anywhere. I spent most of my life in the queer community, witnessing the AIDS crisis in the 1990s, and I also met many transgender people. It always felt like a punch in the gut. I felt like it should have been me, but I kept telling myself, ‘It’s not me.’

When I moved to Berlin in 2017 with my female-assigned partner and our children, everything started to change. We found jobs, she started working at a climbing gym with lots of queer people, including many trans men. One day she came home and said she wanted to have a mastectomy and start taking testosterone. That was when I revealed for the first time that I had tried to transition as a teenager. I had buried it so deep, but now Pandora’s box was open and I couldn’t close it.

We began transitioning at the same time. It was a very positive experience, we were able to support each other. Apart from our appearance, not much changed in our relationship. I had been attracted to men my whole life, so it was quite surprising that I married a woman and had children with her. Ultimately, as it turned out, I wasn’t attracted to women at all.

Since we have children, we didn’t want to change everything overnight. We transitioned slowly, giving the children time to adjust. Our youngest children are now 12 and 10. One day at school, they were asked to draw the flag of the country they come from, and our youngest drew a flag that was half German and half rainbow. She clearly identifies with the queer community! She loves dressing up for Christopher Street Day.

A year and a half ago, I underwent vaginoplasty, and many people asked me if I felt euphoric when I woke up and saw myself in the mirror. To be honest, I felt normal. It was like taking a pill for a headache – you’re not happy, you just feel like yourself. Before the operation, I had a feeling that something was wrong. It’s never too late to transition, no matter how old you are – whether you’re 15 or 70. It’s about feeling complete, about healing the wounds you’ve experienced.

At work, I never fully felt at home among my male colleagues, and I don’t think they ever saw me as one of them. Now I fit in with my female colleagues. They ask me about my clothes, where I bought certain things, which is what I always wanted – to be normal. Although I still don’t quite fit in because of my voice, I feel much more accepted than before.

She describes herself as a woman, and only when talking about queerness or transness does she use the term trans woman to refer to herself. Outside of these conversations, she doesn’t feel the need to use any labels. I think it’s great that I now live in the city where it all began, with a rich queer history that includes figures such as Magnus Hirschfeld. One of the first people to undergo gender reassignment surgery at his institute, Lili Elbe, was also from Denmark, like me.

Getting a manicure gives me a real sense of liberation. It’s the little, seemingly simple things – like trying on trousers without feeling self-conscious about a bulge – that make a huge difference. After the surgery, I can do them without worrying about how others perceive me. For me, the surgery was necessary so that I could live the life I had always dreamed of – a normal life.

Marek, 23, student, Berlin

Growing up, I didn’t have access to a queer community. I come from a smaller town in Poland – we’re known for gingerbread and Nicolaus Copernicus, but that’s about it. My family is very Catholic, so queerness, and especially transness, was never discussed.

I always knew I wasn’t straight; that part was natural. But with transness, I had to break through social narratives. I had no points of reference, so I felt like I was discovering something completely new. I first found the queer community online. I remember telling a friend, ‘I think I’m non-binary, but I can’t tell anyone because my mum will get angry.’

photo: Marit Blossey

Coming out was extremely difficult for me. Not because of being transgender, but because of other struggles, such as depression. That was the hardest part. I don’t like the process of ‘coming out’ — I prefer it when it happens naturally. The most memorable moment for me was when I got a binder for my 17th birthday [ed. – underwear that flattens the chest]. I got it from my friends and it was an amazing feeling. At the time, there were no Polish brands selling binders, so they had to order them from the US.

I started living openly with my identity in middle school, but the physical transition took me some time because I couldn’t afford it. The public healthcare system doesn’t cover these things, so many queer people in Poland rely on fundraising or loans for surgery.

I used to be obsessed with labels. I had a list of things to recite. I learned about queer culture online and wavered between identifying as trans masc or non-binary. Over time, I stopped caring about labels. Now I just say I’m a guy or a queer bitch.

I don’t feel the need to explain myself to anyone anymore. At first, I felt like I had to explain myself, especially since I didn’t have a deep voice. I also experimented with gender-neutral pronouns in Polish. I’m a linguist, so language is a huge passion of mine. There’s a misconception that there are no real gender-neutral options in Polish, but that’s not true!

At one point, I used they/them pronouns, but as I focused on my physical transition, I started to feel more comfortable using he/him. For me, it’s more utilitarian. You need some point of comparison when you’re thinking about your identity. Ten years ago, the discourse was completely different. It was mainly Instagram or Tumblr. I slowly started meeting other queer and trans people in Poland. There is definitely a gravitational pull towards each other.

Nowadays, I think labels can be both helpful and limiting. On the one hand, they help describe our experiences and connect us to a community, which is beautiful.

On the other hand, the whole online discourse around pronouns and labels can seem unproductive.

It should be about building a real community. I am against strict divisions between trans and non-binary people. Creating another binary doesn’t help. We all struggle with similar oppressions, and how we identify ourselves shouldn’t matter. Some trans men, for example, fall into the trap of social expectations of masculinity. If we calmed down a bit, it might be easier.

I think the need to label may stem from a desire to make identity palatable to others. If there is no reflection on why masculinity looks the way it does, we can easily perpetuate the problem. When you become a man, you gain privileges, even if we know it’s wrong. But that’s how the world is constructed.

The most groundbreaking moment for me was my plastic surgery last year. It was so physical and unintellectual. Now I feel so good, mainly because I’m healed and I look great. It wasn’t easy at first, though. I looked like Frankenstein, and the recovery was difficult. It wasn’t an instant ‘Yes!’ moment like some people describe. It was a slow process. But now, the joy of wearing what I want without having to change outfits a million times just to feel comfortable — that’s the best part. I really love it now.

photo: Marit Blossey

Read more from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

Valentyna Salon: Beauty Practices of the Ukrainian Queer Community

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights