Diversity in Brandenburg: Queers Take a Stand

This report was originally published in German on taz

Memorial service at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp on 21 September 2024. Photo: private

Oranienburg, taz | ‘Never again is now, this must apply more than ever with the increasing hate crime and right-wing mobilisations against queer people,’ said Uwe Fröhlich of LSVD Berlin-Brandenburg, opening the memorial event for the 82nd anniversary of the murder operations against homosexual prisoners in Klinkerwerk, a subcamp of Sachsenhausen.

He is standing in front of a memorial plaque in the former cell centre of the concentration camp. In 1992, a plaque was installed here with the inscription: ‘Killed. Kept Quiet. To the Homosexual Victims of National Socialism‘. A rainbow flag is attached to the plaque.

Contents

The memorial event takes place on the same day as the CSD, which will march through Oranienburg for the second time afterwards. Commemorating those murdered and celebrating queer life right now – the memorial has been trying to combine the two since 2022, when the 80th anniversary of the Klinkerwerk killing spree was marked. The idea isn’t new, it has historical precedent: in 1985, a group of West Berlin activists called for a wreath-laying ceremony in Sachsenhausen as part of the CSD and applied for entry into the GDR for this purpose.

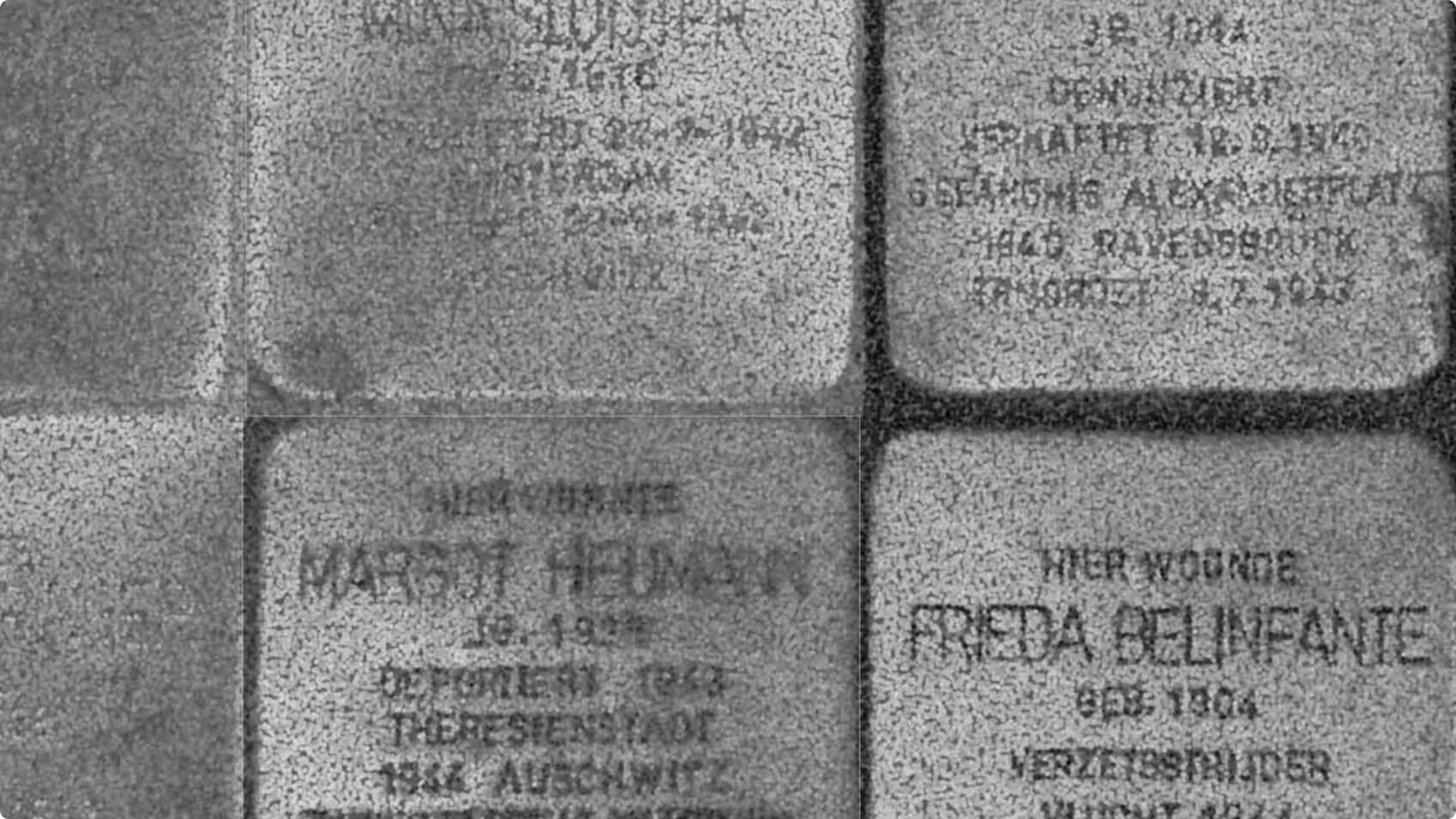

Between 1,000 and 1,200 people were held in solitary confinement in Sachsenhausen as homosexuals under Paragraph 175. Of these, several hundred were systematically killed in Klinkerwerk during July and August 1942. For many survivors, the stigmatisation continued in the GDR and the FRG after 1945. It wasn’t until 2002 that the verdicts under § 175 were repealed.

In their speeches, Fröhlich and Prof. Dr. Axel Drecoll, director of the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation and director of the Sachsenhausen Memorial, explicitly mention the persecution of queer people. Although prisoners in Sachsenhausen were persecuted as homosexuals, there were also all kinds of people who would today be considered ‘queer’, according to Drecoll.

Right-wing counter-demonstration

After Uwe Fröhlich, Axel Drecoll takes the speakers’ podium, where another Pride flag is hanging. ‘It cannot be the case that today you have to be careful about where you are in the city after the CSD and under what security measures a CSD takes place in Oranienburg today.’

In the run-up to the CSD, right-wing extremists had registered a counter-demonstration in Oranienburg. During the hour of remembrance, Drecoll spoke of an obligation towards the persecuted as well as towards groups that are still discriminated against today.

He referenced a recent application by the AfD in the Brandenburg state parliament from August, which called for banning rainbow flags on public buildings. The AfD also wants to withdraw both the non-profit status of associations promoting diversity and their funding. However, all other factions rejected the application.

‘The place where we are sitting here today, the former cell centre, shows where such ideas of dominant identities and a homogeneous society lead.’ Drecoll does not want to live in a world as the right wing imagines it, even if he, as a white hetero-cis man, is not the first target of hostility. In an interview with the taz, he emphasises that it is not enough to be “tolerant”.

‘As a society, we have to understand that diversity and different perspectives are a necessity of life. I feel like I’m losing sight of this right now, and I think that’s devastating.’

Concern about the state elections in Brandenburg the next day and the rise of right-wing sentiment resonates in all the speeches.

Remembrance becomes more abstract

Uwe Fröhlich has been working on Klinkerwerk since the 1990s, fighting to preserve authentic sites of history and pass them on to future generations. He told the taz that the annual memorial events are needed for this, ‘especially since the situation, now that there are no more survivors, is much more abstract’.

He is campaigning to establish a history park on the site of the former forced labour and death camp. This was where prisoners had to build the world’s largest brickworks for construction projects in the imperial capital Berlin. During GDR times, the NVA used the area as a military training and shooting range; today parts of the site belong to the Havel Beton company.

According to Fröhlich, some people in Oranienburg no longer want to have anything to do with their city’s past. Only a few activists usually come to the memorial events. Supported by railbow, a LGTBIQ organisation within Deutsche Bahn, he has organised a joint bus trip from Potsdam and Berlin this year. Another focus of his volunteer work is networking queer structures within Brandenburg and between Berlin and the surrounding area, he emphasises.

The memorial site not only supports the CSD this year, it is also contributing its own activities. In addition to the memorial event, special tours were held on the persecution of queers in Sachsenhausen. The foundation also hung banners with the inscription ‘The dignity of every human being is inviolable. Diversity instead of exclusion!’ at all seven Brandenburg memorial sites.

‘In response to this action and our posting on the CSD, we received so many disgusting hate comments that we had to close the comment function,’ Drecoll told the taz. Nevertheless, he adheres to his understanding of memorial work:

‘We need to integrate more closely into a network of civil society initiatives, schools and extracurricular educational institutions. In doing so, we must address how we reach people and what specific contribution history can make. Our focus needs to shift more towards contemporary phenomena, particularly regarding democratic values and their discussion.’ He notes that achieving this would require additional staff. Drecoll views the discussions with the Brandenburg Ministry of Culture on this issue as constructive.

The results of the municipal elections in June were already a clear warning sign for Drecoll. In the city council meeting in Oranienburg, the AfD became the strongest party with 28.5 per cent of the vote. Although aggressiveness in social media and in e-mails to the memorial is increasing, fortunately the same level of hostility has not yet been seen in Sachsenhausen as in Buchenwald in Thuringia, for example. As director, he has so far refrained from increased security measures; the memorial should remain an open and transparent place for as long as possible.

The railbow bus takes you from the memorial to the CSD assembly point – via detours to avoid passing the right-wingers’ meeting point. Under a blue sky, the participants of Christopher Street Day gather in a car park from 1 p.m.

According to organiser Candy Boldt-Händel, there are about 1,000 to 1,200 people, of whom 200 to 300 people followed the call to travel from Berlin, which was organised within a few days of the right-wing counter-demonstration becoming known. Pop music is playing from loudspeakers, and many people are carrying rainbow and anti-fascist flags. Candy Boldt-Händel makes announcements over a megaphone.

Around 40 Nazis have now gathered at Oranienburger Bahnhof. They are allowed to follow the CSD at a distance of 100 metres and separated by police officers. The organiser calls on the crowd not to leave the demonstration and not to be provoked.

The crowd starts moving, and Candy Boldt-Händel’s face can also be seen on the campaign posters at the roadside. He is the chairman of the Left Party in Oranienburg and the direct candidate for constituency 9, which includes Oranienburg, Liebenwalde and Leegebruch. In the photo, he is wearing a flat cap and smiling at the camera.

Completely funded by donations

‘Out of decency, anti-fascist’ is his election slogan. He wants to use the CSD to promote the visibility and networking of queers in Oranienburg and the region, he tells the taz. At the same time, the connection with the Rosa Winkel commemoration through the foundation is very important in a place like Oranienburg. He describes the mood in the city as very heated and shifting to the right, even in the ranks of democratic parties.

Axel Drecoll is walking well ahead in the demo, wrapped in a rainbow flag, and he has also brought a banner from the memorial. The memorial’s director gives the first speech on the station forecourt, followed by Jirka Witschak from the Queeres Brandenburg state coordination office. Witschak demands 100,000 euros to finance the growing number of CSDs in Brandenburg in the next legislative period.

The demonstration in Oranienburg is completely financed by donations, and it is organised by Boldt-Händel and two fellow campaigners. There was only financing for the subsequent party at the Schlossplatz. Before the march continues, Boldt-Händel invites everyone to a minute’s silence for murdered queers.

Shielded by police batons, the small group of right-wing counter-demonstrators had to wait in front of the station toilet. They had registered 300 people. Otherwise, they hardly came anywhere near the CSD.

The queer demonstration was repeatedly cheered by residents from the houses along the route. Drecoll spontaneously took on the role of chairman of an additional rally opposite the Schlossplatz.

This prevented the right-wingers from positioning themselves within sight of the CSD closing party. All in all, it was not a successful day for the Nazis and an important signal, one day before the Brandenburg state elections. In the Oranienburg constituency 9, the AfD won by 0.1 per cent ahead of the SPD. Candy Boldt-Händel’s hope that the Left Party would enter the state parliament was left unfulfilled.

Read more articles from the Issue

Nothing Found

Criminalized and Invisible: The Long Fight of Queer Ukrainians

Conversion Practices in Germany: Violence in the Name of God

Valentyna Salon: Beauty Practices of the Ukrainian Queer Community

“There is a lot of shame in our community”

How Ukraine’s Queer Artists and Activists are Safeguarding LGBTQIA+ Memory in Wartime

Eastern Queerope Belarus: Stories of Resistance, Repression, and Cultural Renewal

Homophobia at the Core of Putinism’s Ideology

Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Beauty as a Shelter: Ukrainian Women Rebuild Their Lives in Bucharest’s Salons

Angels from the East

Passing the Paintbrush: Historic Queer Jewish Artists in Berlin

Searching for Oneself at Random: How LGBTQI+ Communities Emerged in the Donetsk Region, 1991-2014

“I Have Nothing to Hide”

When We Stopped Hating Ourselves: Gay Life Under Persecution In Poland And Germany

How Queer Soldiers Shape Ukraine’s Defense And Future

Unsafe in The Country of Origin

The Bible, Putin, AfD: Four Misanthropic Myths to Abandon

Queer Resistance in Ukraine: Between War and Disinformation

No Safe Place

“A Place You Can Always Come To”: Shaping Polish Diasporic Queer Communities in Germany

19th Century ‘Friendships’ to 90s Drag: Eastern Queerope Returns

Asylum Discourse: What Are “Safe” Countries of Origin for Queers?

Queer Fronts

Moving Stories: LGBTQIA+ Ukrainian Refugees

Beyond the Binary

Queer Rights and Marriage Equality Under War, Authoritarianism, and Democracy

Gaps in Remembrance – Queer Biographies during National Socialism

Queer and Trans People Have Always Been Here. These Are Their Stories

New Stories from Eastern Queerope

The Prisoners with the Pink Triangle

Queerly Beloved: Romani Resistance Through the Ages

Intertwined Queer Stories: First LGBTIQ+ Museum in Eastern Europe

“The Smaller the Settlement, the Greater the Influence of Religion”: Belarusian Trans Non-Binary Activist in Poland

Queer Holocaust Voices – the Price of Silence

Forgotten Stories of Eastern European Queer Heroes

“I Accept Myself with All My Features”: Ukrainian Queer Person and Her Identity in Catholic Poland

Belarusian on Bisexuality, Theatre and Emigration

Shelters, Help and Support: How Uzhhorod Became a New Home for Queer People

Being Yourself. How Kharkiv’s LGBTQI Community Fights for Their Rights